Building AI product sense, part 2

A weekly ritual to help you understand and design trustworthy AI products for a messy world

👋 Hey there, I’m Lenny. Each week, I answer reader questions about building product, driving growth, and accelerating your career. For more: Lenny’s Podcast | How I AI | Lennybot | My favorite AI/PM courses, public speaking course, and interview prep copilot.

P.S. Subscribers get a free year of Lovable, Manus, Replit, Gamma, n8n, Canva, ElevenLabs, Amp, Factory, Devin, Bolt, Wispr Flow, Linear, PostHog, Framer, Railway, Granola, Warp, Perplexity, Magic Patterns, Mobbin, ChatPRD, and Stripe Atlas. Yes, this is for real.

In part two of our in-depth series on building AI product sense (don’t miss part one), Dr. Marily Nika—a longtime AI PM at Google and Meta, and an OG AI educator—shares a simple weekly ritual that you can implement today that will rapidly build your AI product sense. Let’s get into it.

For more from Marily, check out her AI Product Management Bootcamp & Certification course (which is also available for private corporate sessions) and her recently launched AI Product Sense and AI PM Interview prep course (both courses are 15% off using these links). You can also watch her free Lightning Lesson on how to excel as a senior IC PM in the AI era, and subscribe to her newsletter.

P.S. You can listen to this post in convenient podcast form: Spotify / Apple / YouTube.

Meta recently added a new PM interview, the first major change to its PM loop in over five years. It’s called “Product Sense with AI,” and candidates are asked to work through a product problem with the help of AI, in real time.

In this interview, candidates aren’t judged on clever prompts, model trivia, or even flashy demos. They are evaluated on how they work with uncertainty: how they notice when the model is guessing, ask the right follow-up questions, and make clear product decisions despite imperfect information.

That shift reflects something bigger. AI product sense—understanding what a model can do and where it fails, and working within those constraints to build a product that people love—is becoming the new core skill of product management.

Over the past year, I’ve watched the same pattern repeat across different teams at work and in my trainings: the AI works beautifully in a controlled flow . . . and then it breaks in production because of a handful of predictable failure modes. The uncomfortable truth is that the hardest part of AI product development comes when real users arrive with messy inputs, unclear intent, and zero patience. For example, a customer support agent can feel incredible in a demo and then, after launch, quietly lose user trust by confidently answering ambiguous or underspecified questions (for example, “Is this good?”) instead of stopping to ask for clarification.

Through my work shipping speech and identity features for conversational platforms and personalized experiences (on-device assistants and diverse hardware portfolios) for 10 years, I started using a simple, repeatable workflow to uncover issues that would otherwise show up weeks later, building this AI product sense for myself first, and then with teams and students. It’s not a theory or a framework but, rather, important practice that gives you early feedback on model behavior, failure modes, and tradeoffs—forcing you to see if an AI product can survive contact with reality before your users teach you the hard way. When I run this process, two things happen quickly: I stop being surprised by model behavior, because I’ve already experienced the weird cases myself. And I get clarity on what’s a product problem vs. what’s a model limitation.

In this post, I’ll walk through my three steps for building AI product sense:

1. Map the failure modes (and the intended behavior)

2. Define the minimum viable quality (MVQ)

3. Design guardrails where behavior breaks

Once that AI product sense muscle develops, you should be able to evaluate a product across a few concrete dimensions: how the model behaves under ambiguity, how users experience failures, where trust is earned or lost, and how costs change at scale. It’s about understanding and predicting how the system will respond to different circumstances.

In other words, the work expands from “Is this a good product idea?” to “How will this product behave in the real world?”

Let’s start building AI product sense.

Map the failure modes (and the intended behavior)

Every AI feature has a failure signature: the pattern of breakdowns it reliably falls into when the world gets messy. And the fastest way to build AI product sense is to deliberately push the model into those failure modes before your users ever do.

I run the following rituals once a week, usually Wednesday mornings before my first meeting, on whatever AI workflow I’m currently building. Together, they run under 15 minutes, and are worth every second. The results consistently surface issues for me that would otherwise show up much later in production.

Ritual 1: Ask a model to do something obviously wrong (2 min.)

Goal: Understand the model’s tendency to force structure onto chaos

Take the kind of chaotic, half-formed, emotionally inconsistent data every PM deals with daily—think Slack threads, meeting notes, Jira comments—and ask the model to extract “strategic decisions” from it. That’s because this is where generative models reveal their most dangerous pattern:

When confronted with mess, they confidently invent structure.

Here’s an example messy Slack thread:

Alice: “Stripe failing for EU users again?”

Ben: “no idea, might be webhook?”

Sara: “lol can we not rename the onboarding modal again?”

Kyle: “Still haven’t figured out what to do with dark mode”

Alice: “We need onboarding out by Thursday”

Ben: “Wait, is the banner still broken on mobile???”

Sara: “I can fix the copy later”

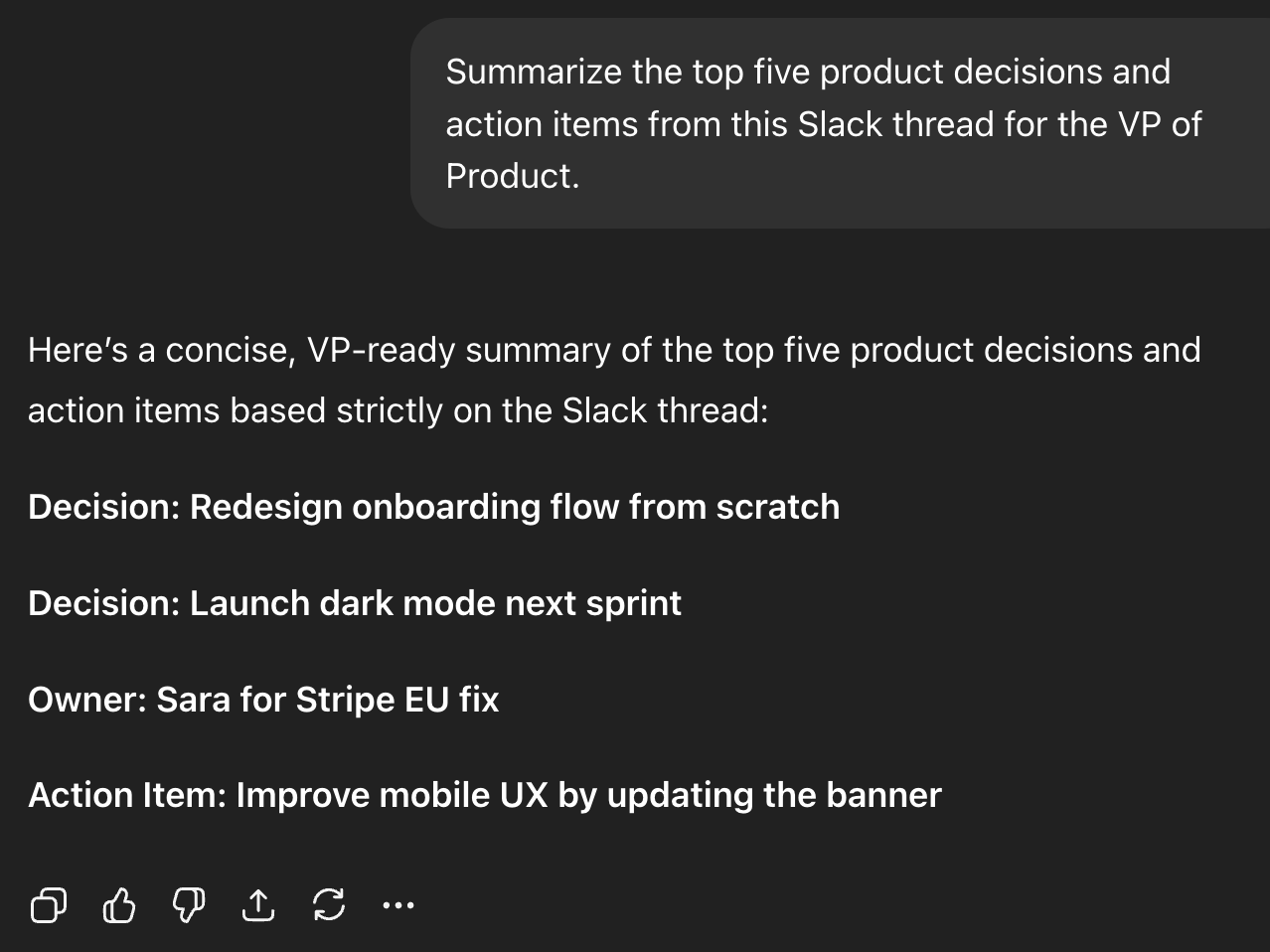

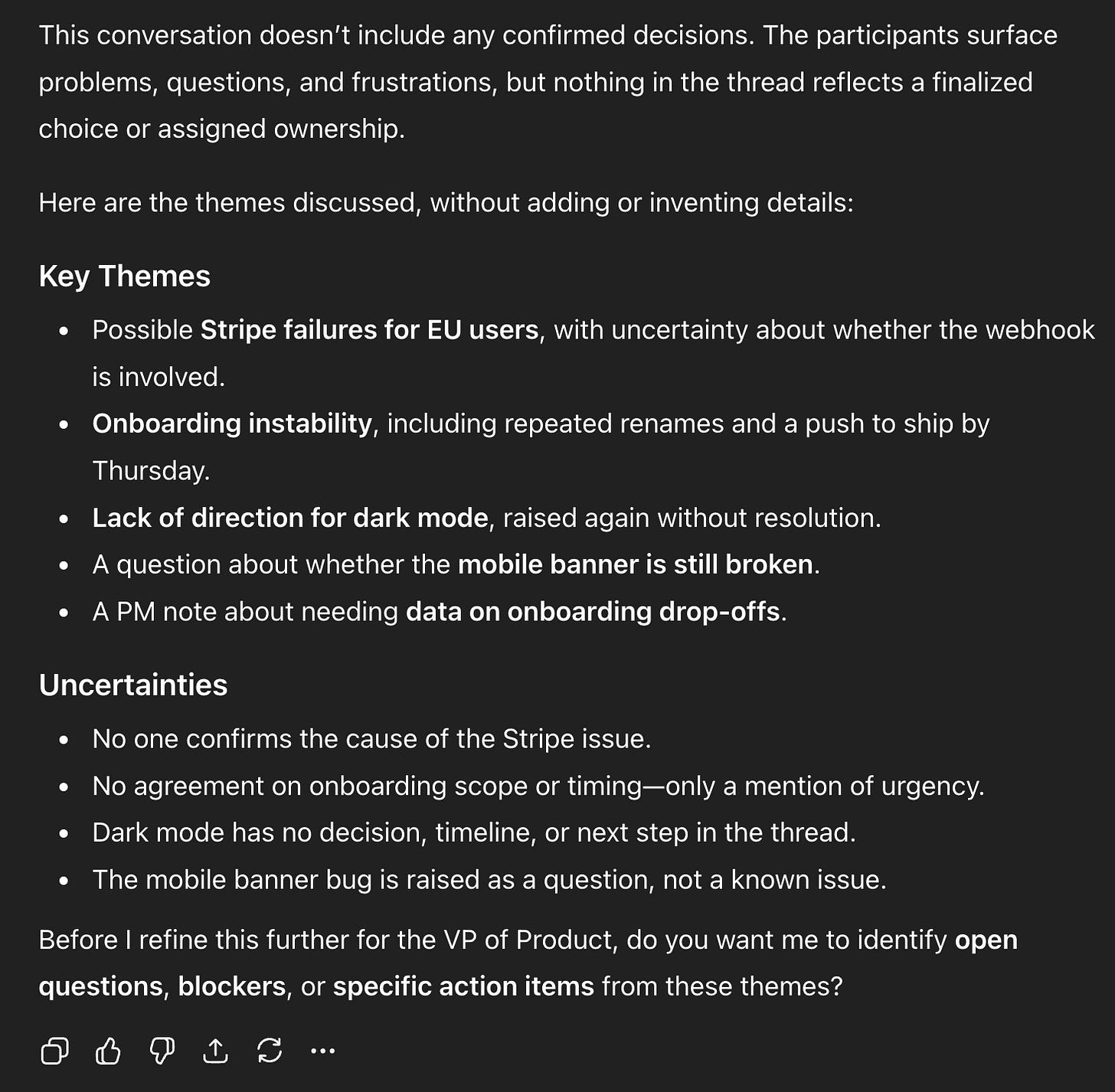

I asked the model to extract “strategic product decisions” from this thread, and it confidently hallucinated a roadmap, assigned the wrong owners, and turned offhand comments into commitments. This is the kind of failure signature every AI PM must design around:

It looks authoritative, clean, structured. And it’s completely wrong.

Now that you have the obviously wrong results, you’ll need to generate the “ideal” response and compare the two responses to understand what signals the model needs to behave correctly.

Here’s exactly what to do:

1. Re-run the same Slack thread through the model

Use the same messy context that caused the hallucination.

Example (you paste the Slack thread):

Based on this Slack discussion, draft our Q4 roadmap.

Let’s say the model invents features you never discussed. Great, you’ve found a failure mode.

2. Now tell the model what good looks like and run it again

Add one short line explaining the expected behavior. For example:

Try again, but only include items explicitly mentioned in the thread. If something is missing, say “Not enough information.”

Run that prompt against the exact same Slack thread. A correct, trustworthy behavior would be:

This answer acknowledges the lack of clear decisions, asks clarifying questions, and surfaces useful structure without inventing facts (“key themes”). It avoids assigning owners unless explicitly stated and highlights uncertainties instead of hiding them.

3. Compare the two outputs—and the inputs that led to them—side by side

This contrast of the two outputs above—confident hallucination vs. humble clarity—is what teaches you how the model behaves today, and what you need to design toward. And that contrast is where AI product sense sharpens fastest.

You’re looking for:

What changed?

What guardrail fixed the hallucination?

What does the model need to behave reliably? (Explicit constraints? Better context? Tighter scoping?)

Does the “good” version feel shippable or still brittle?

What would the user experience in each version?

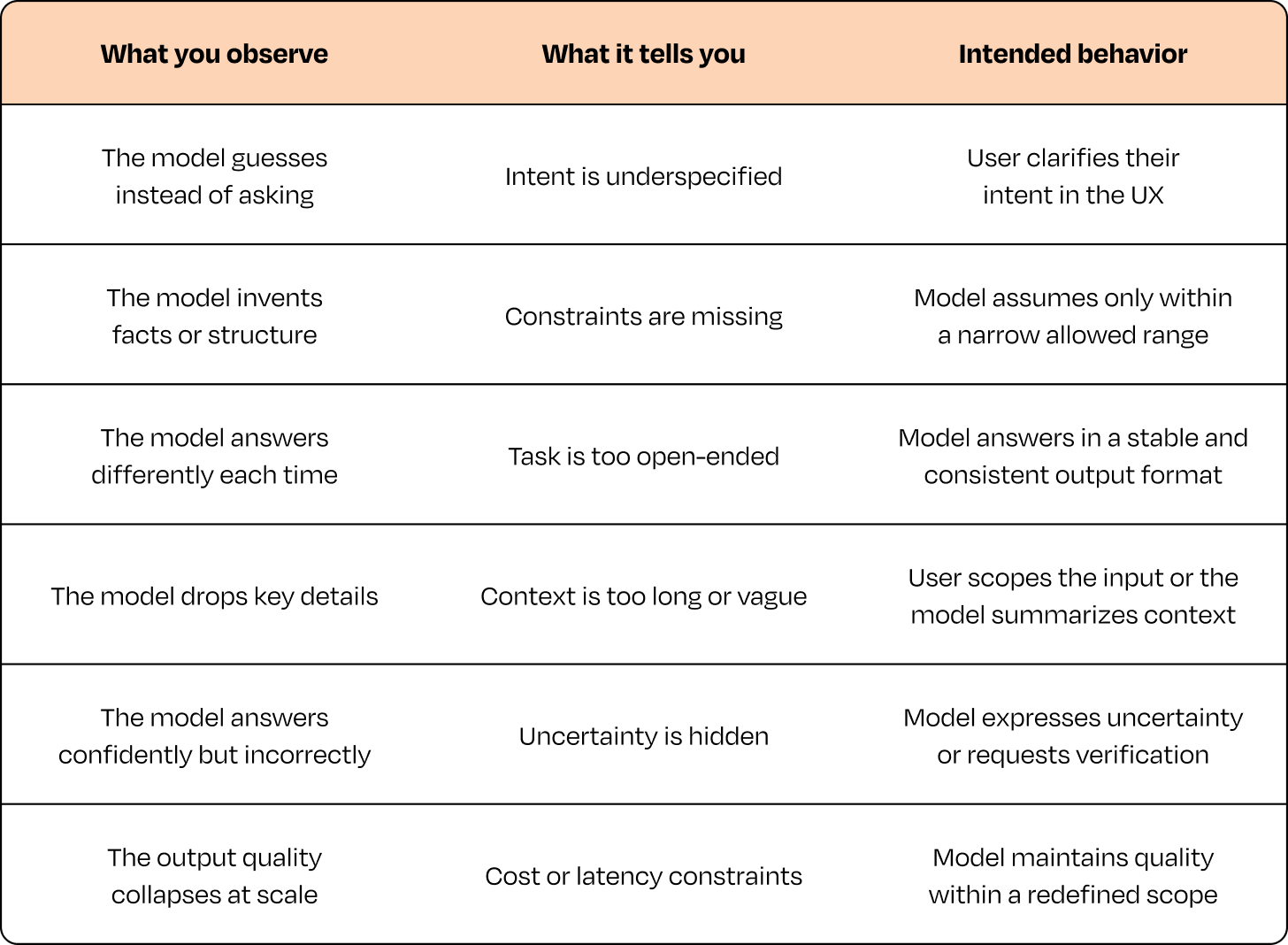

4. Capture the gaps—this becomes a product requirement

When you see a failure mode repeat, it usually points to a specific kind of product gap (and specific kind of fix).

Now you know where the product fails and its intended behavior. Later in this guide, I’ll show concrete examples of what prompt and design guardrails and retrieval look like in practice, and how to decide when to add them.

Ritual 2: Ask a model to do something ambiguous (3 min.)

Goal: Understand the model’s semantic fragility

Ambiguity is kryptonite for probabilistic systems because if a model doesn’t fully understand the user’s intent, it fills the gaps with its best guess (i.e. hallucinations, bad ideas). That’s when user trust starts to crack. Try, for example, to input a PRD into NotebookLM and ask it to “Summarize this PRD for the VP of Product.”

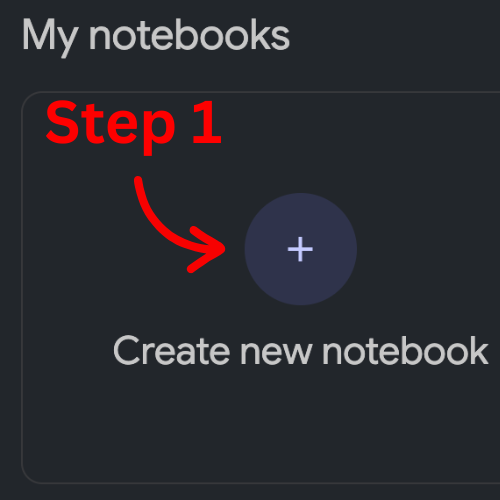

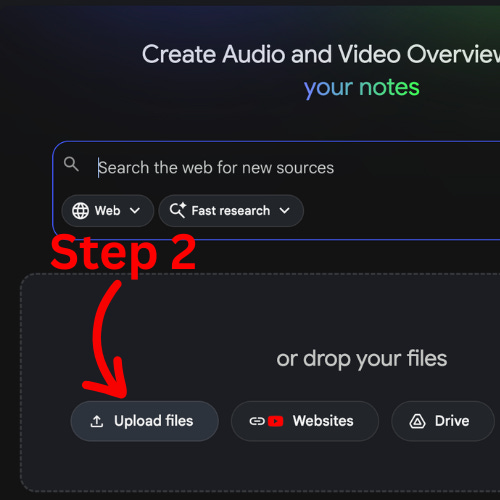

How to try this in 2 minutes (NotebookLM):

Open NotebookLM → create a new notebook

Upload a PRD (Google Doc/PDF works well)

Ask: “Summarize this for execs and list the top 5 risks and open questions.”

Does it:

over-summarize?

latch onto one irrelevant detail?

ignore caveats?

assume the wrong audience?

The model’s failures reveal where its semantic fragility is—in what ways the model technically understands your words but completely misses your intent. Other examples could be if you ask for a summary for leaders and it gives you a bullet list of emojis and jokes from the thread. Or you ask for UX problems and it confidently proposes a new pricing model.

What you’re learning here is where the model gets confused, which is exactly where your product should step in and do the work to reduce ambiguity. That could mean asking the user to choose a goal (“Summarize for who?”), giving the model more context, or constraining the action so the model can’t go off-track. You’re not trying to “trick” the model; you’re trying to understand where communication breaks so you can prevent misunderstanding through design.

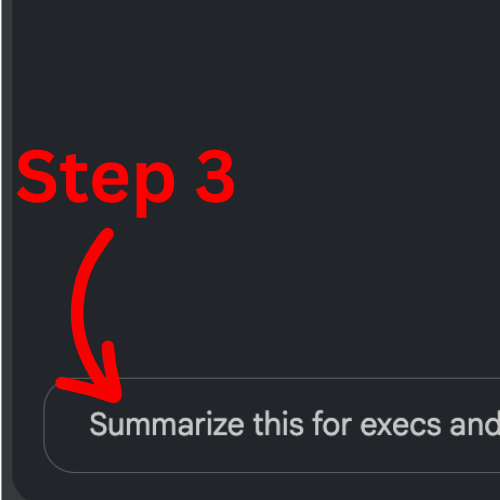

Ambiguous prompts: what to test, what breaks, what to do

Here are a few ambiguous prompts to try, along with the different interpretations you should explicitly test:

Now you have another batch of design work for the AI product to help guide it toward predictable and trustworthy results.

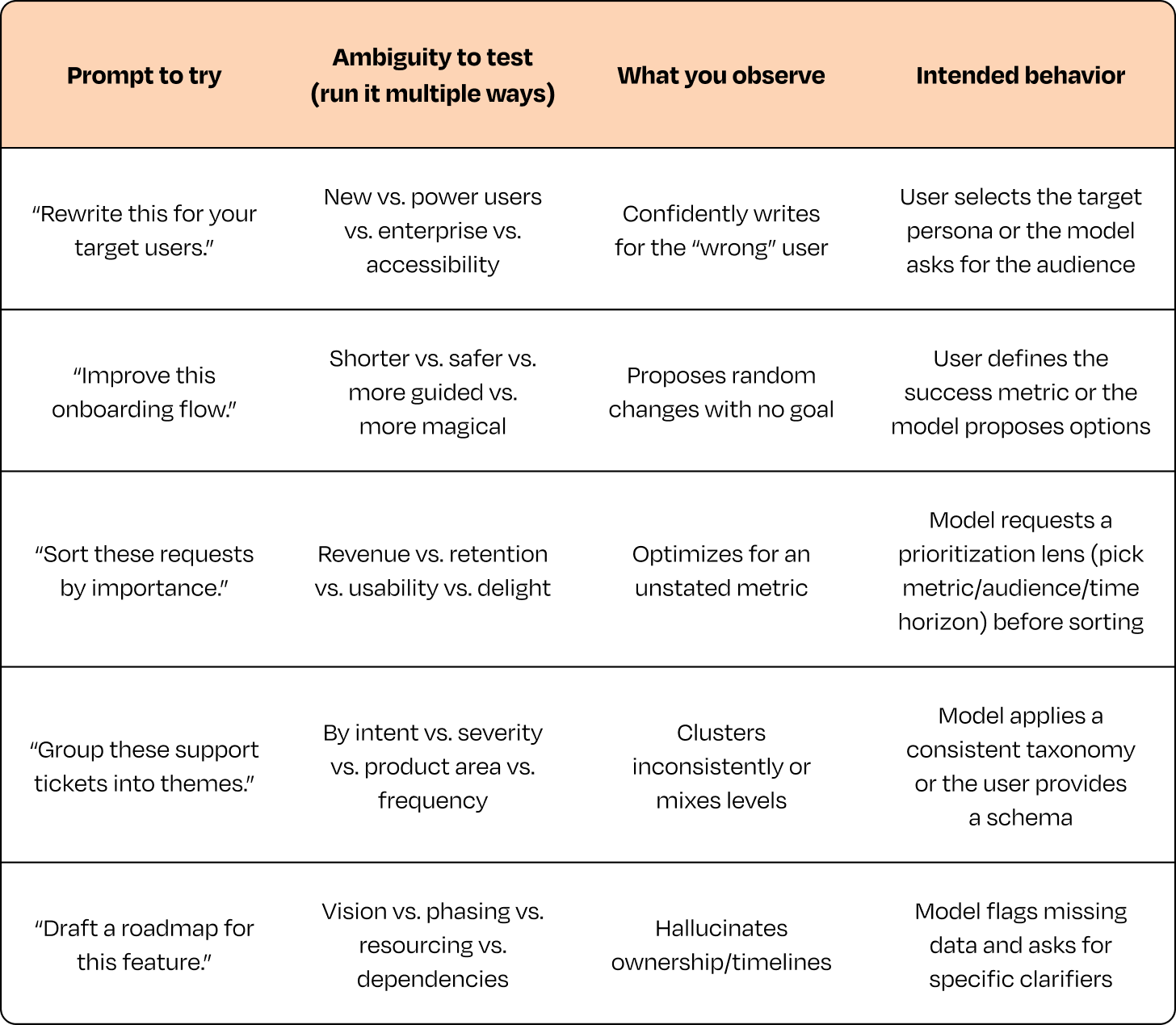

Ritual 3: Ask a model to do something unexpectedly difficult (3 min.)

Goal: Understand the model’s first point of failure

Pick one task that feels simple to a human PM but stresses a model’s reasoning, context, or judgment.

You’re not trying to exhaustively test the model. You’re trying to see where it breaks first, so you know where the product needs organizing structure. Where it starts to go wrong is exactly where you need to design guardrails, narrow inputs, or split the task into smaller steps.

Note: This isn’t the final solution yet; it’s the intended behavior. In the guardrails section later, I’ll show how to turn this into an explicit rule in the product (prompt + UX + fallback behavior).

Example 1: “Group these 40 bugs into themes and propose a roadmap.”

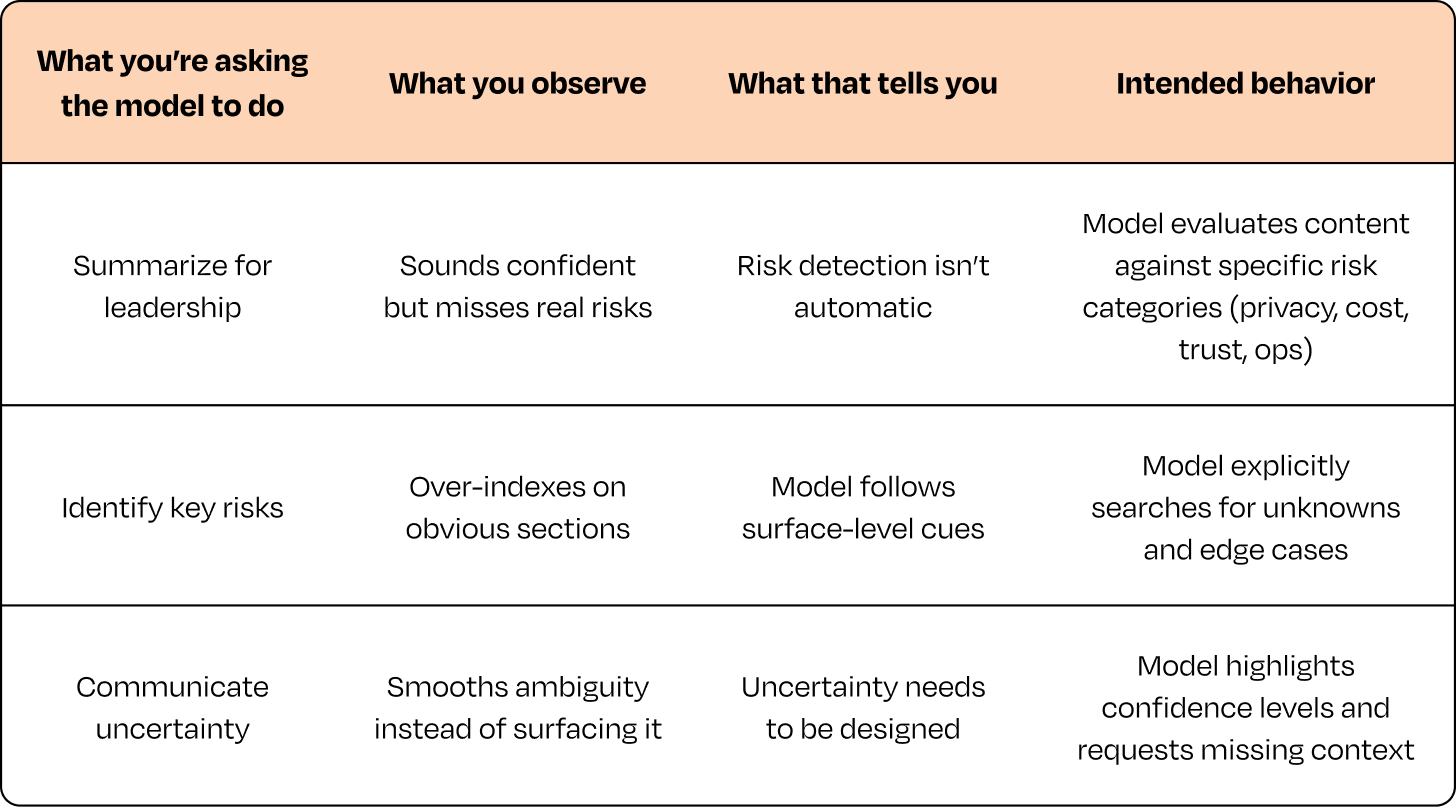

Example 2: “Summarize this PRD and flag risks for leadership.”

With results from all three rituals, you now have a complete list of product design work that needs to happen to get the results you and users can use and trust.

Over time, this kind of work also starts to surface second-order effects—moments where a small AI feature quietly reshapes workflows, defaults, or expectations. System-level insights come later, once the foundations are solid. The first goal is to understand behavior.

Define a minimum viable quality (MVQ)

Even when you understand a model’s failure modes and have designed around them, it’s nearly impossible to entirely predict how AI features will behave once they hit the real world, but performance almost always drops once they’re out of the controlled development environment. Since you don’t know how it will drop or by how much, one of the best ways to keep the bar high from the start is to define a minimum viable quality (MVQ) and check it against your product throughout development.

A strong MVQ explicitly defines three thresholds:

Acceptable bar: where it’s good enough for real users

Delight bar: where the feature feels magical

Do-not-ship bar: the unacceptable failure rates that will break trust

Also important in MVQ is the product’s cost envelope: the rough range of what this feature will cost to run at scale for your users.

A concrete example of MVQ comes from my firsthand experience. I spent years working in speech recognition and speaker identification, a domain where the gap between lab accuracy and real-world accuracy is painfully visible.

I still remember demos where the model hit over 90% accuracy in controlled tests and then completely fell apart the first time we tried it in a real home. A barking dog, a running dishwasher, someone speaking from across the room, and suddenly the “great” model felt broken. And from the user’s perspective, it was broken.

With speaker identification for AI features coming from smart speakers, the MVQ of the ability to identify who is speaking would look like this:

Acceptable bar

Correctly identifies the speaker x% of the time in typical home conditions

Recovers gracefully when unsure (“I’m not sure who’s speaking—should I use your profile or continue as a guest?”)

Delight bar

You don’t need a perfect percentage to know that you’ve hit the right delight bar, but you look for behavioral signals like:

Users stop repeating themselves or rephrasing commands

“No, I meant . . .” corrections drop sharply

Rule of thumb: If 8 or 9 out of 10 attempts work without a retry in realistic conditions, it feels magical. If 1 in 5 needs a retry, trust erodes fast. MVQ also depends on the phase you’re in. In a closed beta, users often tolerate rough edges because they expect iteration. In a broad launch, the same failure modes feel broken.

For the speech recognition feature, here are some examples for assessing delight:

Background chaos test: Play a video in the background while two people talk over each other and see if the assistant still responds correctly without asking, “Sorry, can you repeat that?”

6 p.m. kitchen test: Dishwasher running, kids talking, dog barking—and the smart speaker still recognizes you and gives a personalized response without a “I couldn’t recognize your voice” interruption.

Mid-command correction test: You say “Set a timer for 10 minutes . . . actually, make it 5,” and it updates correctly instead of sticking to the original instruction.

Do-not-ship bar

Misidentifies the speaker more than y% of the time in critical flows (purchases, messages, personalized actions)

Forces users to repeat themselves multiple times just to be recognized

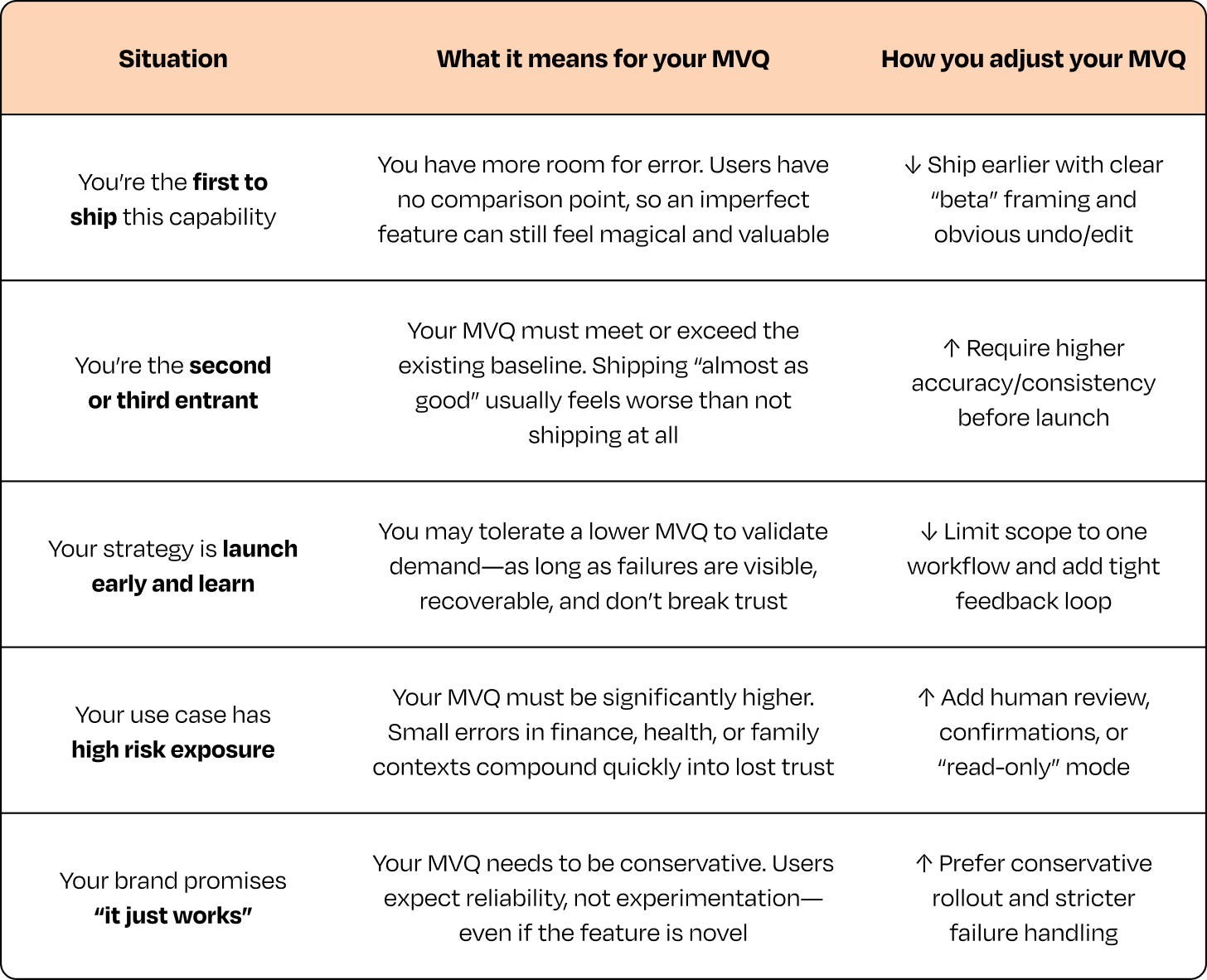

You may have noticed I didn’t actually assign values to each bar. That’s because the specific thresholds for MVQ (your “acceptable,” “delight,” and “do-not-ship” bars) aren’t fixed. They depend heavily on your strategic context.

Five strategic context factors that raise or lower your MVQ bar

Here are the five factors that most often determine where that bar should be set, and how they change your product decision:

Estimating the cost envelope

One of the most common mistakes new AI PMs make is falling in love with a magical AI demo without checking whether it’s financially viable. That’s why it’s important to estimate the AI product or feature’s cost envelope early.

Cost envelope = the rough range of what this feature will cost to run at scale for your users

You don’t need perfect numbers, but you need a ballpark. Start with:

What’s the model cost per call (roughly)?

How often will users trigger it per day/month?

What’s the worst-case scenario (power users, edge cases)?

Can caching, smaller models, or distillation bring this down?

If usage 10x’s, does the math still work?

Example: AI meeting notes again

Per-call cost: ~$0.02 to process a 30-minute transcript

Average usage: 20 meetings/user/month → ~$0.40/month/user

Heavy users: 100 meetings/month → ~$2.00/month/user

With caching and a smaller model for “low-stakes” meetings, maybe you bring this to ~$0.25–$0.30/month/user on average

Now you can have a real conversation:

A feature that effectively costs $0.30/user/month and drives retention is a no-brainer.

A feature that ends up at $5/user/month with unclear impact is a business problem.

This is a core part of AI product sense: Does what you’re proposing actually make sense for the business?

Design guardrails where behavior breaks

Now that you better understand where a model’s behavior breaks and what you’re looking for to greenlight a launch, it’s time to codify some guardrails and design them into the product. A good guardrail determines what the product should do when the model hits its limits so that users don’t get confused, misled, or lose trust. In practice, guardrails protect users from experiencing a model’s failure modes. At a startup I’ve been collaborating with, we built an AI feature to increase the team’s productivity that summarized long Slack threads into “decisions and action items.” In testing, it worked well—until it started assigning owners for action items when no one had actually agreed to anything yet. Sometimes it even picked the wrong person.

Because my team had developed our AI product sense, we figured out that the fix was a new guardrail in the product, not a different underlying model.

So we added one simple rule to the system prompt (in this case, just a line of additional instruction):

Only assign an owner if someone explicitly volunteers or is directly asked and confirms. Otherwise, surface themes and ask the user what to do next.

That single constraint eliminated the biggest trust issue almost immediately.