How to do AI analysis you can actually trust

Four prompting techniques to prevent AI’s most common mistakes

👋 Hey there, I’m Lenny. Each week, I answer reader questions about building product, driving growth, and accelerating your career. For more: Lenny’s Podcast | Lennybot | How I AI | My favorite AI/PM courses, public speaking course, and interview prep copilot

P.S. Get a full free year of Lovable, Manus, Replit, Gamma, n8n, Canva, ElevenLabs, Amp, Factory, Devin, Bolt, Wispr Flow, Linear, PostHog, Framer, Railway, Granola, Warp, Perplexity, Magic Patterns, Mobbin, ChatPRD, and Stripe Atlas by becoming an Insider subscriber.

The problem with AI is that the output always looks confident—even when it’s full of lies: made-up quotes, false insights, and completely wrong conclusions. As today’s guest author, Caitlin Sullivan, puts it, “These mistakes are invisible until a stakeholder asks a question you can’t answer, or a decision falls apart three months later, or you realize the ‘customer evidence’ behind a major investment actually had enormous holes.”

A user-research veteran, Caitlin has been at the bleeding edge of using AI for user research. She’s trained hundreds of product and research professionals at companies big and small on effective AI-powered customer research and advised teams at companies like Canva and YouTube. Below, she shares her four most effective techniques for getting real, trustworthy, and actionable user insights out of ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, or your LLM of choice. Let’s get into it.

For more from Caitlin, find her on LinkedIn and in her new course, Claude Code for Customer Insights.

P.S. You can listen to this post in convenient podcast form: Spotify / Apple / YouTube.

Everyone’s “analyzing” customer data with AI. But everyone’s also getting answers full of slop: hallucinations, wrong conclusions, and “insights” that just parrot back what you already told it.

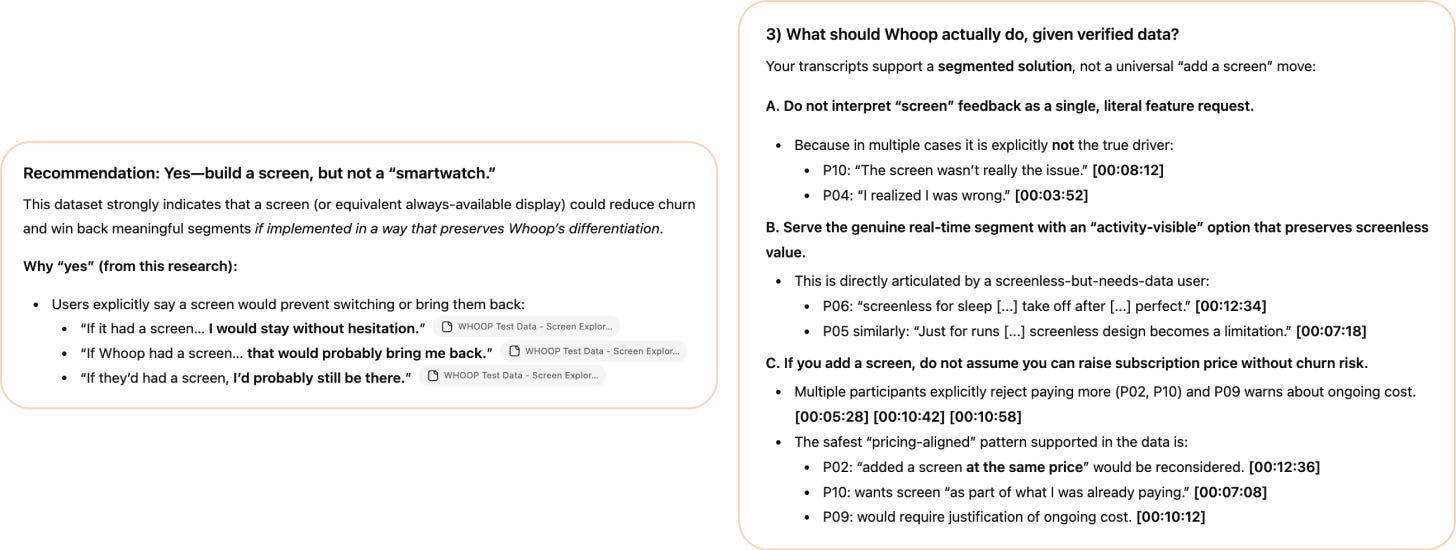

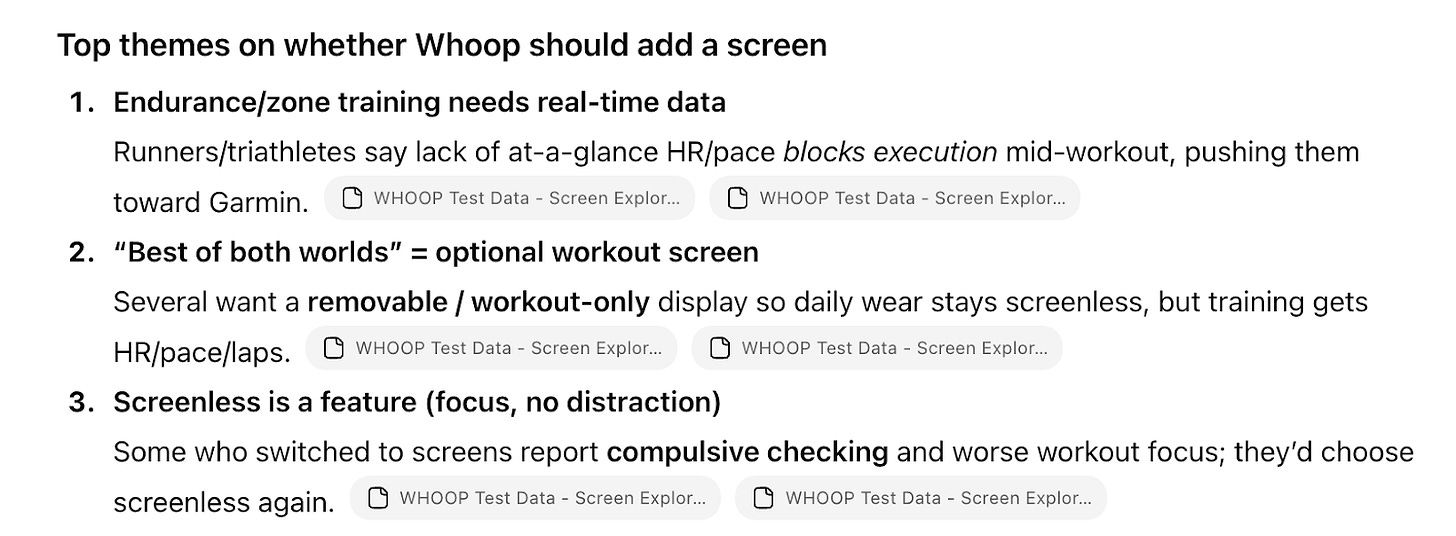

Put the same customer conversation transcripts into two models and get a choose-your-own-adventure experience in return. Each model will give you a different narrative, different “evidence,” and wildly different product recommendations, with the same high level of confidence. Below are two real outputs from that experiment. One is misleading. One is trustworthy. Can you tell which is which?

When they’re side by side, you might spot the problems with the one on the left. But that’s not how this works in practice. You get one output, it reads confidently, and you build your next decision on top of it and never see what’s missing. This is exactly why verification matters.

Here’s what separates these answers: the left output cherry-picks three enthusiastic quotes and leaps to a confident recommendation (“Yes, build a screen”), without questioning whether those quotes represent the full dataset. It looks persuasive, but it’s the AI equivalent of confirmation bias.

The right output does something harder. It challenges the surface-level request (“Do not interpret screen feedback as a single, literal feature request”), segments users by actual need, and flags pricing risk with specific participant timestamps you can verify. It’s messier and doesn’t oversimplify things, but it’s real.

The difference between the two examples above comes down to crucial steps in my workflow to address common failure modes of AI analysis. Those steps force LLMs to maintain the customer’s exact words, dig deep beyond superficial patterns, and catch contradictions in customer stories that will skew final recommendations. Without those checks, false but convincing-looking insights go into a deck and influence a million-dollar decision in the wrong direction.

In this post, I’ll show you how to get relevant and verified insights you can trust. You’ll learn about four failure modes that silently break your AI-supported insights:

Invented evidence

False or generic insights

“Signal” that doesn’t guide better decisions

Contradictory insights

I’ll also teach you my prompting techniques to prevent and catch these errors before they lead to the wrong final decisions. These tactics work across Claude, ChatGPT, Gemini, and with interviews, surveys, or any qualitative or mixed data you’re trying to make sense of with the help of AI.

Why AI struggles with customer research data

Before we get into failure modes, you need to understand what’s difficult about this kind of data for AI in the first place. Models fail with interviews and surveys in different ways.

Interviews are unstructured and messy.

A 45-minute research interview is a messy, wandering conversation. A participant may contradict themself. They go on tangents. They say something important at minute 8 and reframe it completely at minute 35.

LLMs handle this by imposing structure and jumping to conclusions a bit too fast. They find clean themes immediately, pull quotes that fit them best, produce tidy summaries, and call it a day.

But real analysis requires sitting with the mess, noticing contradictions, weighing tangents, and catching tone shifts. Without explicit guidance, AI flattens all of that into something that looks like insight but misses what actually matters.

Even when surveys look structured, they’re not.

You’d think a CSV would be easy to parse. Rows and columns—what’s complicated about that? A lot.

A column of 200 responses to “Why did you cancel?” is just as messy as interview data; maybe worse, because you have none of the context. In an interview, you remember that they hesitated, or had just complained about a specific feature. In a survey, you get “It wasn’t for me” and nothing else.

Your CSV may also not be as clean as you think. Different tools export differently. SurveyMonkey might put question text in headers, while Qualtrics exports headers with internal codes. Some exports even include metadata columns—timestamps, internal tags—sitting right next to customer responses, without clear differentiation. If you don’t tell AI which columns contain the customer’s voice and which to ignore, it analyzes everything as signal. I’ve seen AI treat an internal note (“flagged for follow-up”) as something the customer said.

Even “structured” columns hide complexity. A header that says “Q3_churn probability” tells AI nothing about the scale, the question wording, or whether 5/5 is good or bad.

When analyzing interviews, AI models require help with structure, evidence extraction, and contradiction detection. With surveys, they require help with interpretation, column disambiguation, and understanding what sparse responses actually mean.

The four failure modes below hit both data types and anything similar. Fixing these will typically 10x both the reliability and relevance of your AI analysis results.

What each LLM is best used for

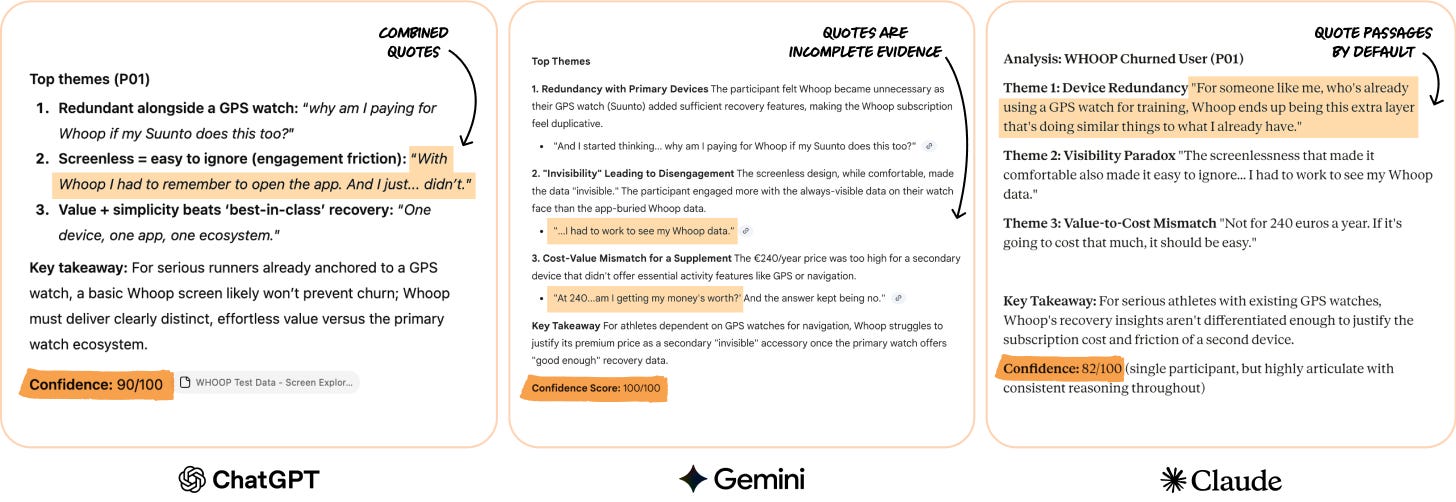

Not all LLMs are equal for analysis work. I’ve run the same analysis process across Claude, ChatGPT, and Gemini over 100 times and worked with discovery tool product teams like Maze testing prompts across models to see what delivers.

Here’s what you need to know about each model:

Claude: Best for thorough analysis with depth and nuance. Delivers more quotes and covers more ground with less pushing. The tradeoff: it gives you the whole brain dump, so themes aren’t always “proven”—you get breadth, not just the safe patterns.

Gemini (and NotebookLM): Best for highly evidenced themes and now video analysis. Gives you fewer themes but with stronger grounding. Expect to prompt multiple times to get completeness, and to ask for longer quotes. Unique advantage: it can analyze non-verbal behaviors in video, which the others can’t (yet).

ChatGPT: Best for final framing and stakeholder communication. Most creative of the three—including with “verbatim quotes,” unfortunately. Least reliable for real evidence (combines quotes), but excels at packaging relevant findings for a specific audience.

Let me show you what I mean:

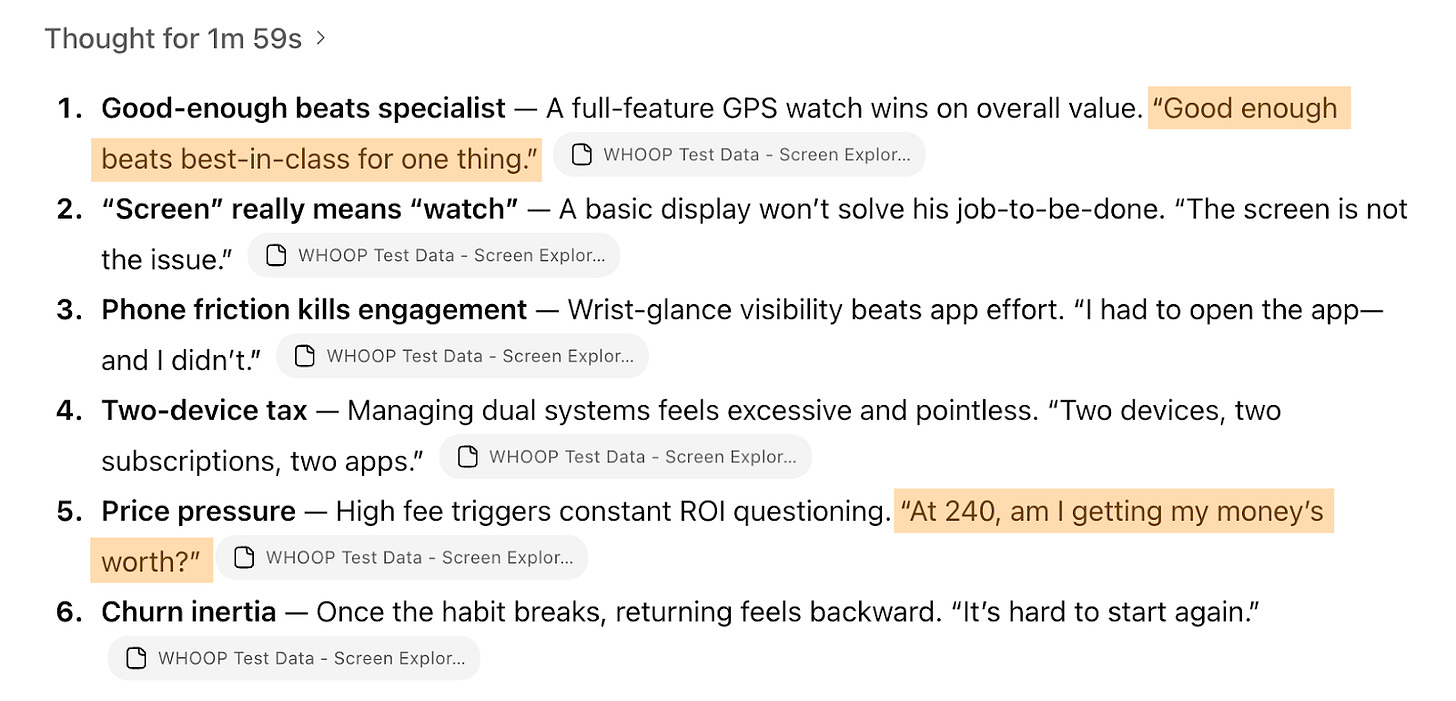

Unless I give these models more instruction, there are meaningful differences in output. There’s theme overlap, but ChatGPT misses the user’s value/price sensitivity reaction, and all three models give different confidence scores and quotes—some verbatim, some summarized.

This becomes obvious when we can see all three side by side, but most teams have one LLM enterprise account and won’t see the shortcomings of the one they use. ChatGPT summarizes and mashes together verbatim quotes, Claude is more conservative with confidence scores, and Gemini often chooses too-short snippets of customer voice.

My recommendation: If you have a choice, use Claude for analysis work. It covers more ground while staying rooted in the actual data. You get depth and breadth without as much pushing. The tradeoff is that it doesn’t filter for you. You’ll often get validated patterns and half-formed hypotheses presented on equal ground, and you’ll need to verify that themes are well-evidenced. But that’s a better starting point than having to prompt three times before being sure your analysis partner hasn’t missed something.

A note on examples: For consistency, the examples throughout this post typically use ChatGPT. It’s still the most widely used model among my client teams and students, and it’s also the most prone to the specific failure modes I’m covering. The fixes work and improve results across all three models.

Four ways AI data analyses lie to you, and how to fix them

After more than 2,000 hours of testing customer discovery workflows with AI, I’ve found that there are four distinct failure modes for AI analysis—and reliable fixes for each one that consistently work across platforms, data types, models, and workflows.

Failure mode #1: Invented evidence

What the problem looks like

Despite massive improvements across most reasoning models, hallucinations are still abundant. When I look over the shoulders of product people running analysis, I see two hallucination types all the time:

Completely fictionalized quotes (still happens among all three major LLMs)

Frankenstein quotes sewn together from multiple sources that somewhat represent what the user was saying . . . but isn’t actually their words (particularly common in ChatGPT)

Both types go unnoticed unless you’re checking every quote manually, but both are often caused by the way you prompt. You can pretty easily and accidentally trigger ChatGPT to combine multiple customer quotes in ways that can harm our understanding of what the customer was saying. When you add phrases like “max. 100 words” or “for each theme, give a punchy and representative quote that captures it (≤12 words),” you’ll almost always get mash-ups. Highlights in the example below are combinations like this, not the customer’s exact real words.

Why this happens

LLMs don’t retrieve quotes like a search engine; they generate text that’s statistically likely given the context. Generation and retrieval are fundamentally different. The model predicts what a quote should look like. If the context is about phone-checking frustration, it generates plausible phone-checking-frustration language. Sometimes that matches the original, sometimes it’s a near-miss, and sometimes it’s fabricated.

“Verbatim” is also an ambiguous word to prompt a model with. Exact characters? Can punctuation differ? What about filler words? Where does the quote start and end? The model fills these gaps with assumptions you never see. Even participant IDs and timestamps can be faked. A citation like “[P03, 14:30]” looks authoritative but means nothing if the quote is invented.

The fix: Quote selection rules + verification

The solution to this problem, no matter your model, data type, or workflow, has two parts. First, define what a valid quote actually looks like—your quote “rules”—which removes the ambiguity that lets AI fill in gaps. And then verify that quotes in the resulting AI analysis actually exist before you allow the model to use them.

1. Define your quote “rules”

Add this to your analysis prompt:

QUOTE SELECTION RULES

Start where the thought begins, and continue until fully expressed

Include reasoning, not just conclusions

Keep hedges and qualifiers — they signal uncertainty

Include emotional language when present

Cite with participant ID and approximate timestamp [P02 ~14:30]

Do not combine statements from different parts of the interview

If a quote would exceed 3 sentences, break it into separate quotes

This removes ambiguity. The model now knows what “verbatim” means to you: where to start, where to stop, what to include, what not to combine.

I always encourage client teams and course participants to think critically about what makes a quote “good” to them. You’ll likely get much better results right away with my prompt snippet (it’s my favorite copy-paste inclusion) but even better results if you add your own definitions.

2. Verify before you use

After your initial analysis, use this verification prompt to have the LLM confirm that these are real quotes:

QUOTE VERIFICATION

For each quote in the analysis above:

Confirm the quote exists verbatim in the source transcript

If the quote is a close paraphrase but not exact, flag it and provide the actual wording

If the quote cannot be located, mark as NOT FOUND

Output format:

Quote: [the quote]

Status: VERIFIED / PARAPHRASE / NOT FOUND

If paraphrase: Actual wording: [what they said]

Location: [Participant ID, timestamp, or line number]

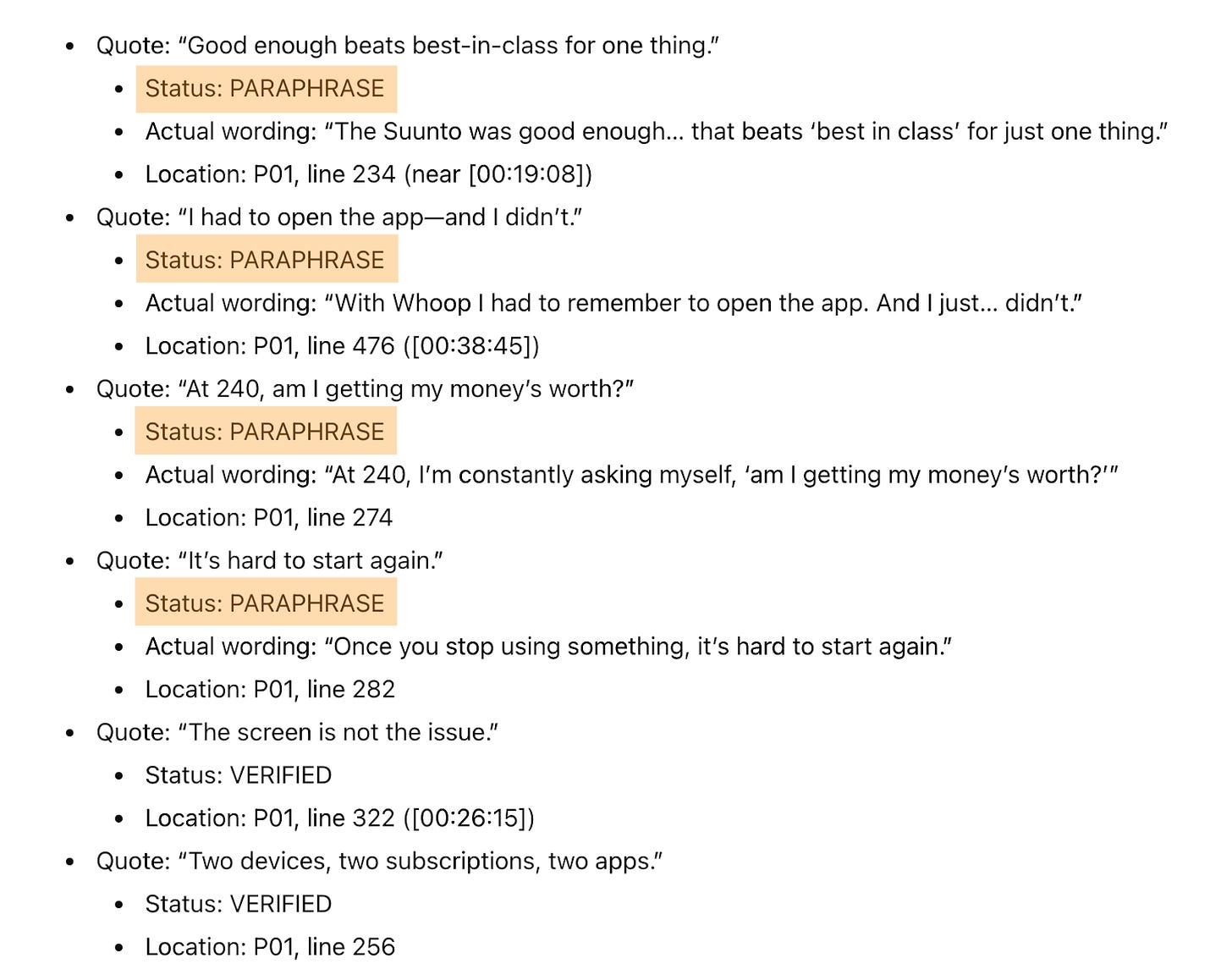

Here’s what happens when you run that:

A majority of the quotes in the previous ChatGPT output were paraphrased, not original verbatim customer statements. This happened with a request for a small set of quotes, so imagine what happens when you’re digging through 20 interviews and getting just as many patterns back.

Without verification, “quotes” like these end up in your deck attributed to a real participant. Sometimes it’s no big deal. Other times, it’s the difference between product language that strongly resonates and messaging that doesn’t convert.

This often takes just an extra five minutes, depending on how much data you’re dealing with. But it catches errors that would otherwise undermine the evidence behind your product decisions.

Failure mode #2: False or generic insights

What the problem looks like

AI finds themes that are too broad and generic to act on, or biased by what you accidentally primed it with. In interviews, you get themes that could describe any product in your category. I hear this constantly from PMs: “The AI analysis just told me what I already know” or “These insights are too generic. I can’t do anything with them.”

They get outputs like:

“Price is a factor in decisions”

“People value reliability”

“Users want more real-time information”

True, probably, but useless for tough decisions—we need to get deeper than that. These themes could come from so many studies out there. Since I’m working with my fake Whoop data here, they could also easily come from any wearables study.

Themes like these don’t tell you whether your users want this new feature you’re exploring enough to justify the investment, or whether adding it would alienate the customers who chose you specifically because you’re different.

Why this happens

AI defaults to finding consensus, because LLMs are pattern-finding machines. They surface the (obvious) patterns that easily rise to the top, finding what multiple participants mentioned, and then they generate a pattern-matched theme.

The truly most important insight might be something only a few people said in this particular batch of interviews but that, if shared by more customers, would be a noteworthy business signal. Or the most important insight might even be the tension between what people say they want and what their behavior suggests.

LLMs also bring priors from training. If the model has seen thousands of churn analyses where price is the #1 theme, it will weight toward price even if your full dataset doesn’t support it.

In surveys, that tendency to superficially pattern-match is even worse. When someone writes “It’s not for me” when cancelling, AI has to guess what that means. Without guidance, it’ll likely lump that response with others into a generic “value perception” theme. But “not worth it” could mean:

Too expensive for what I’d get

Too data-intensive and I’m not a serious enough athlete

I don’t want another device to charge

I need a screen and Whoop doesn’t have one

It’s one response with four completely different implications for your product decision. Multiply that ambiguity across hundreds of survey responses, and your “themes” become meaningless averages that don’t make decisions any easier.

LLMs are trained to find consensus and compress information. Specificity and valuable edge cases get lost. And if your prompt mentions “pricing issues,” watch how many responses suddenly get coded as pricing-related.

In some cases, that can be helpful, because the model makes sure all outputs are relevant to the specific thing you’re working on. But in many cases, it can be biased cherry-picking from the start.

Here’s an example:

These could describe any wearables study. We can’t make a hardware decision from this.

Another example:

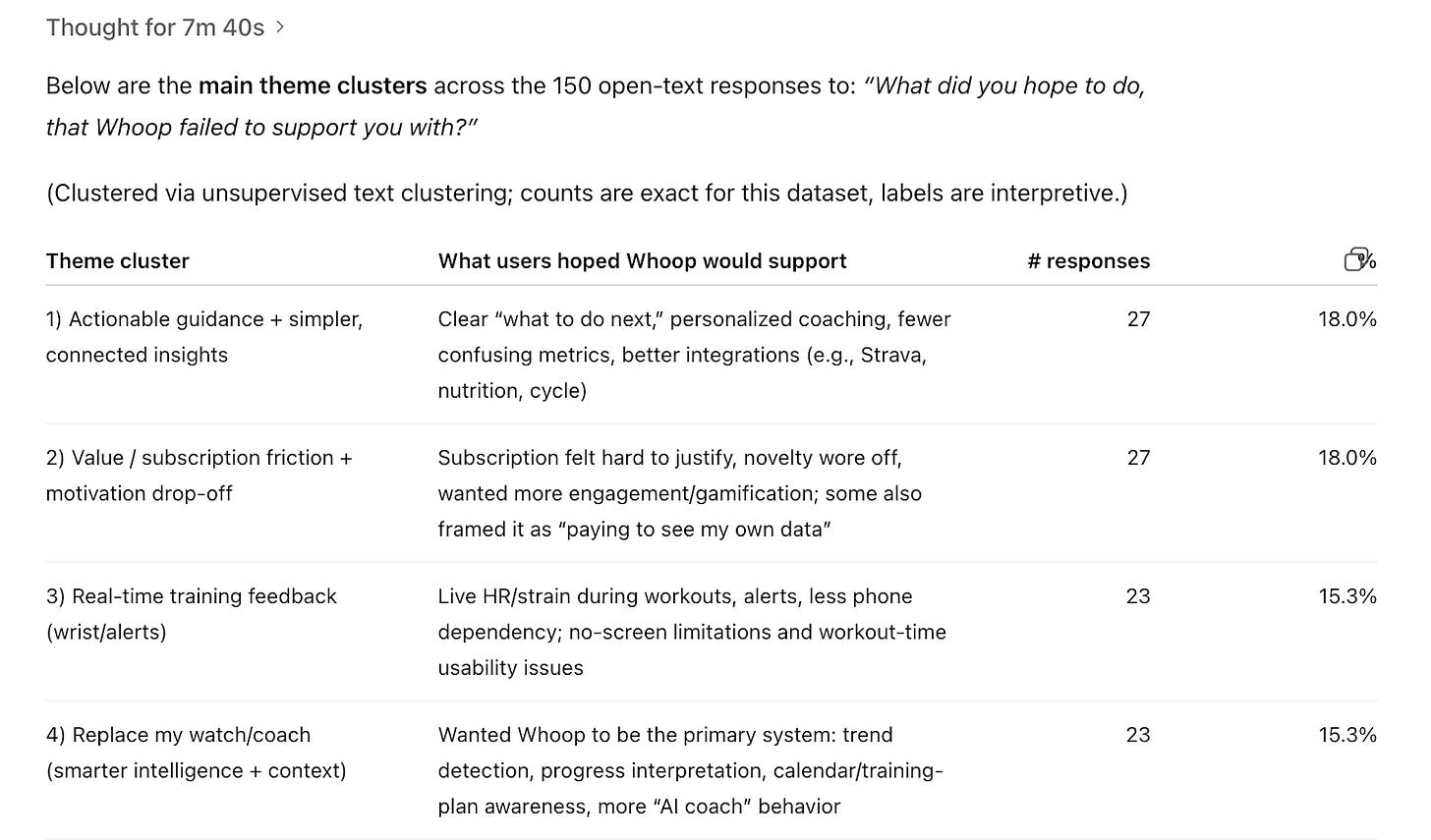

I asked ChatGPT to find me theme clusters and counts for the churn survey question “What did you hope to do that Whoop failed to support you with?”

The results below are clusters that don’t help us make this decision either. So 18% of churned respondents need “more actionable guidance,” which sounds like a job-to-be-done. But there are too many possible directions within that cluster for us to make a decision more easily. Should Whoop focus on clearer metrics or workout plans, or both? Plus, most of this has nothing to do with our screen decision.

When we ask AI to cluster survey responses, we need to give it clear direction with context, or we’re leaving room for mediocre decisions and more manual work.

The fix: Context loading that actually guides interpretation

Most people are used to prompt frameworks that have sections like Role, Context, Task, Format, and so on. Context to most of us means including a few lines of background information in the prompt, somewhere near the beginning. When we’re using AI for analysis, that often focuses on the point of this current customer discovery. Think: objectives, hypotheses, and what part of the product we’re working on.

In the past year, I’ve seen more and more people turn the prompt’s “context” section into four paragraphs of anything they could think of about their work, often dictated in a stream of thought while eating lunch.

But neither three lines of objectives nor the whole unstructured backstory is good enough. Effective context loading has at least four components that shape how AI interprets everything that follows:

Project context tells AI the scope and stakes. “Exploring whether to add a screen” is a specific decision with constraints. “Doing customer research” is vague, so AI defaults to generic analysis because you gave it no frame.

Business goal tells AI what you’re trying to achieve. If you need to know whether a feature would attract new users vs. alienate existing ones in order to prioritize building it, say that. AI will weight evidence toward answering your question and addressing your decision, not the decision it assumes you’re making.

Product context gives AI domain knowledge. Without it, AI interprets “I want to see my data” generically. With it, AI understands that statement in the context of a screenless wearable competing against Apple Watch—a completely different interpretation.

Participant overview tells AI who’s speaking. “I need real-time data” from a churned Garmin switcher means something different than the same words from a loyal user who’s never tried a competitor. AI can only weight evidence correctly if it knows who the evidence is coming from.

The good news is that a lot of what I see people add to the context in their prompts is superfluous. You often don’t need as much information as you think, but it needs to be clear, direct, and relevant information, like the four items above.

For interviews, put this context into an analysis prompt (or use as a single prompt):