How to find the perfect name

A step-by-step playbook for naming in a noisy and AI-driven product landscape

👋 Welcome to Lenny’s Newsletter. Each week, I tackle reader questions about building product, driving growth, and accelerating your career. For more: Lennybot | Lenny’s Podcast | How I AI | Lenny’s Reads | Courses

P.S. Annual subscribers get a free year of 15+ premium products: Lovable, Replit, Bolt, n8n, Wispr Flow, Descript, Linear, Gamma, Superhuman, Granola, Warp, Perplexity, Raycast, Magic Patterns, Mobbin, and ChatPRD (while supplies last). Subscribe now.

Vercel, Azure, Pentium, PowerBook, Sonos, Swiffer, BlackBerry, Impossible Foods—if you recognize these names, you know David Placek’s work. Over 40 years, David and his team at Lexicon Branding have named nearly 4,000 brands and companies, pioneering the field of brand naming. Building on his popular recent podcast appearance, David breaks down his tried-and-tested step-by-step naming process, including a four-part framework you can use with your team to find the perfect name for any product or company.

You can also listen to this post in convenient podcast form: Spotify / Apple / YouTube.

If you’re launching a new product or company, the name you choose may be the single most important decision you make. A great name creates a foundation of trust with consumers, gives meaning and voice to a new idea, and builds cumulative advantage over time. Names that are too descriptive and too comfortable won’t generate the interest or memorability that a new brand needs to succeed.

In my more than 40 years leading Lexicon Branding, we’ve created names like Swiffer, Sonos, BlackBerry, Azure, Impossible Foods, Vercel, Windsurf, and many more. In that time, I’ve seen too many teams treat naming as a low priority with marginal results. It’s one of the highest-stakes parts of building a brand, yet it’s too often delegated to junior staff or tackled in group brainstorming sessions.

The difference between a good-enough name and the right name is the difference between solid performance and breakthrough success. The right name is a competitive advantage that no one can take away from you.

Nobody knew Codeium until it became Windsurf.

People didn’t care about computer processors until Intel introduced Pentium.

No one loved mopping until Procter & Gamble created the Swiffer.

Nobody wanted to eat a Maraxi. But an Impossible Burger? Even meat lovers flocked to it.

Why names must work harder than ever

AI and technologies like VR are reshaping how people discover, evaluate, and experience brands. We’ll see more innovation and new brands in the next five years than in the previous 20. This creates six key challenges:

Unprecedented competition: More players, more noise, more choice.

Trademark clutter: Congestion across all 45 trademark classes. In the U.S., there are over 5,500,000 registered trademarks.

Attention scarcity: Audiences are distracted and overwhelmed.

Global digital commerce: Names must work across languages, cultures, and platforms simultaneously.

Institutional skepticism: People have learned not to believe hype.

Information overload: A signal must be stronger to stand out.

For startups, the challenge is even greater. Your name must attract both investors and early adopters.

The three pillars of effective naming

To address these challenges, focusing on three dimensions will increase your likelihood of creating a truly effective name. While we have been using these three pillars for many years at Lexicon, the first pillar, “Build for trust,” has increased in importance. The marketplace is moving so fast now that a new brand must gain momentum early or it will fail. Trust is a key factor in momentum.

1. Build for trust.

The right name inspires both trust and imagination. Consider Microsoft’s Azure cloud services brand. The team at Microsoft considered calling it “Microsoft Cloud Services,” but there’s no news in such a straightforward name. When we presented this name, one senior Microsoft executive called it “a dumb idea.” Turns out, it wasn’t so dumb after all. It offered familiarity as a word while generating significant interest based on customer interviews. The sounds in Azure provide additional benefits: the “z” sound creates a strong signal, while the “zure” (like “sure”) creates a smooth experience.

2. Communicate an original idea. Never describe.

Anyone can describe what a company does. For example, Infoseek is descriptive and one-dimensional. A name like that is boring and likely to have a thousand similar names swirling around in the competitive landscape. On the other hand, Google—an invented, surprising word—signals a new idea. In our research, we know we have a winner when customers tell us, “They’re not like the other guys.” TripActions is another example of a very descriptive name. As the company grew and developed an expense platform as well, TripActions no longer worked even descriptively. We created Navan, a palindrome that links to travel (“navigation”) but offers the originality that the company wanted to help them move into financial services—and the flexibility to grow into new industries. Since the rebrand in 2023, Navan revenues have grown from $150 million to over $500 million in 2025.

3. Be accessible.

The human brain doesn’t like complexity—or remember it very well. Make sure your name is easy to process and contains familiar components. We used the simple and familiar geographic term “Outback” to create Subaru’s most successful brand to date.

Case study: Intel’s Pentium

The story of Intel’s Pentium is a perfect example of how to structure a naming process to get an effective result.

Intel needed to differentiate its next-generation processor. Up to that point, chip manufacturers only used model numbers. While Intel’s 486 processor outperformed AMD’s 486, consumers perceived the two as identical. Can you blame them?

Our first criterion was to develop a name that would differentiate Intel’s processor from all others. Based on interviews with Intel executives, we agreed that the new name needed to capitalize on the success of the “Intel Inside” campaign. “Prochip” was an internal favorite at the time. But our research gave us clear creative direction: develop a name that sounds and looks like an element inside the computer that is fundamental to performance. “Pentium” looked and sounded like familiar, science-based words such as “sodium” and “uranium,” using the “-ium” suffix for fluency. But while it was a familiar-seeming word, it was unexpected for the category—a strategic advantage that made it stick out and stick in people’s memory.

Here’s a key insight: Invented names like Pentium actually take less money to build into brands than existing words—despite a common myth to the contrary. Invented names signal “new and innovative” better than most other name types. Further, because they are unexpected rather than descriptive or suggestive names, they generate more attention. Humans are more interested in the new.

Research conducted by Lexicon in six markets provided data showing that “Pentium” delivered the magic Intel needed. Within months, consumers were asking for Pentium computers—to the chagrin of Dell, HP, and others.

The Lexicon process: beyond brainstorming

Creating the right name requires more than one or two brainstorming sessions. Those brainstorming sessions—especially with four or more participants—can get bogged down by everyone’s need to be right, and the peer pressure to agree on a popular solution. As a result, they usually deliver marginal results. When we work with clients, we stick to key process principles:

Set high standards, not narrow objectives. Aim for fresh, energetic ideas, not just basic objectives like “support the product’s positioning” or “keep it under seven letters.”

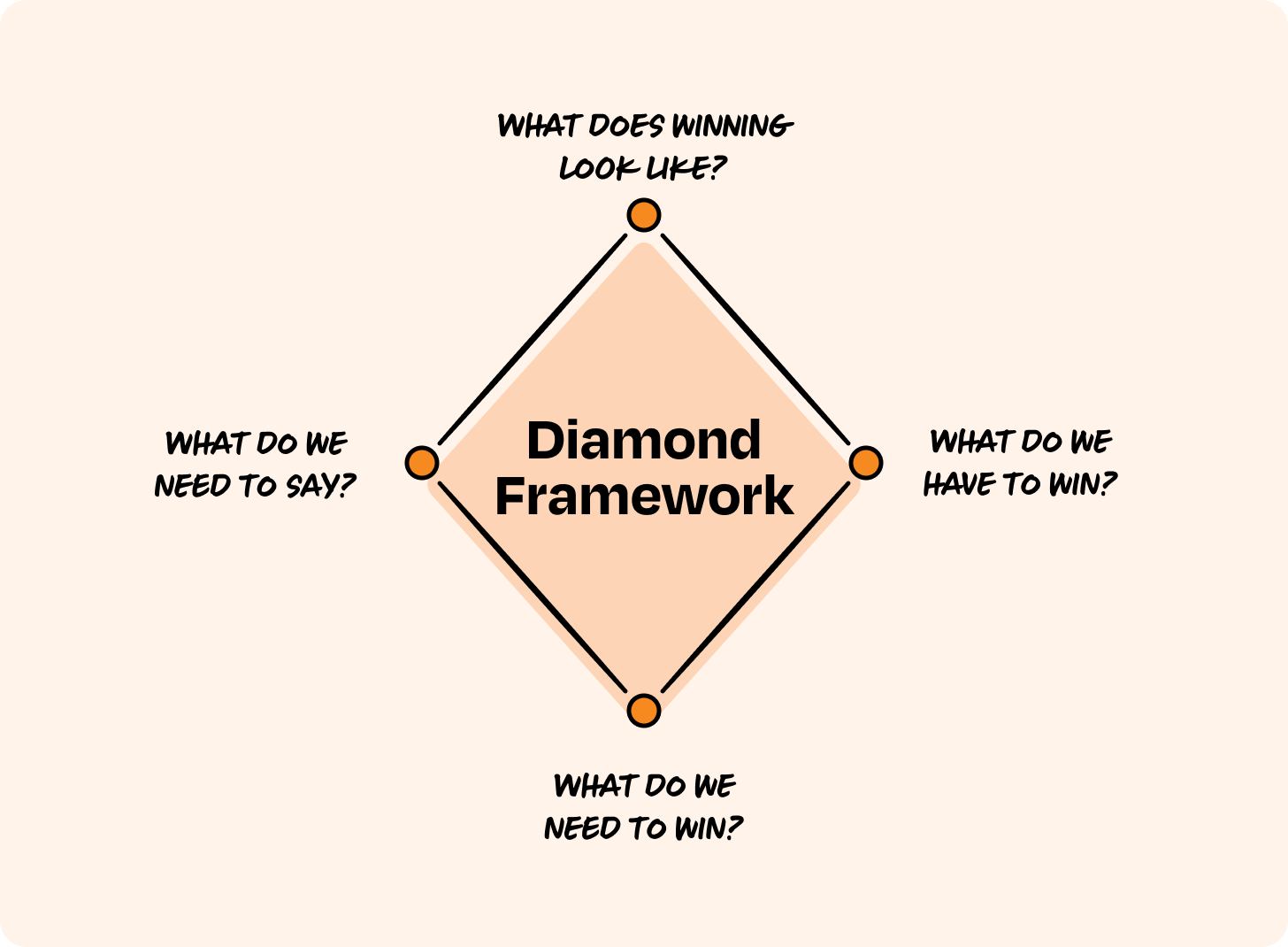

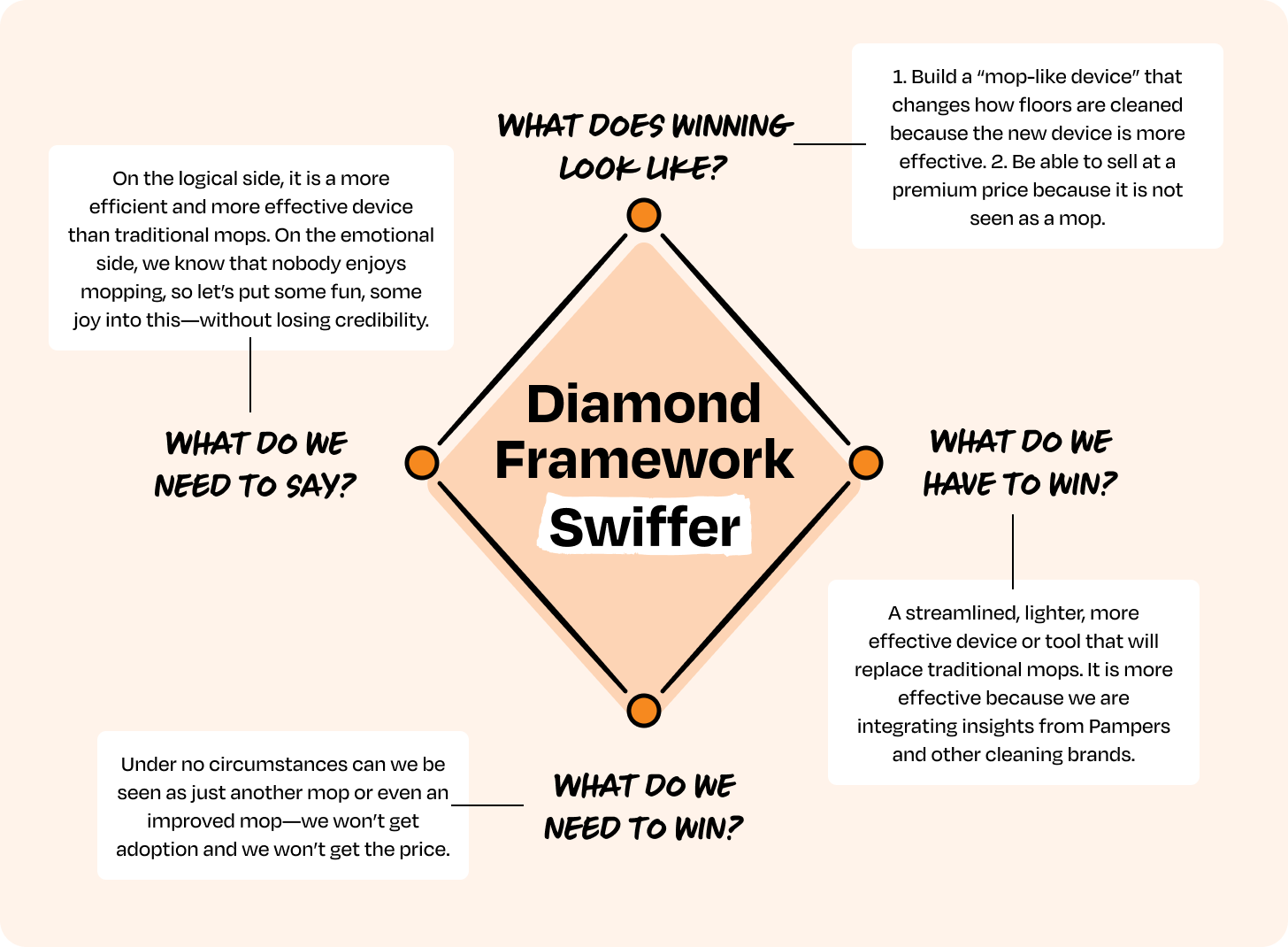

We use a framework called the Diamond Framework to force clarity on business, marketing, and naming strategy. At the start of any project, we ask:

What does winning look like?

What do we have to win?

What do we need to win?

What do we need to say?

This creates alignment on the role of the name versus other brand elements like design and messaging. Here are the results of the exercise we did while working with P&G to develop the Swiffer brand name.

Quantity breeds quality. Developing a brand name is a treasure hunt. You need to explore, and then explore again. And you need to explore in places where you think there may be no chance of finding the name. Naming is hard work. We recommend generating at least 1,000 creative ideas before selecting a shortlist of 50 to 100 candidates. (We usually generate thousands.)

Don’t underestimate the power of sound. Imagine the sound of your brand before you start naming. Should your name sound fast? Full? Reliable? Coca-Cola’s Dasani water brand exemplifies this. An invented name with the Latin word for health (“san”) in the middle, a “da” sound that delivers a crisp, clean experience, and an “i” sound that feels light and slim at the end.

Case study: Swiffer and the invention of a new category

P&G had invented what they called a new mop, but it wasn’t really a mop. We started by interviewing 25 people about cleaning routines. Some enjoyed washing windows, others polishing furniture. No one liked mopping. One participant said, “It’s just moving dirt and grease from one place to another.” Another said, “Mopping is just not fun.”

We reframed the problem around fun, eliminating names like “Promop” or “EffiClean.” One small team explored toys, other exotic vacations, and other easy-to-use tools. Our linguists focused on the actions and sounds of cleaning—sweeping, wiping, washing. When we merged the work, “Swiffer” sat in the middle.

The best names don’t describe reality; they change it. Swiffer made mopping feel like a quick, joyful action. In research with our linguistic network and consumers, Swiffer was selected over 80% of the time as the new brand they would be most interested to try.

Case study: The story of Vercel

When we started working with a company called Zeit, the team and technology were impressive. Using our Diamond Framework, we defined winning as being the most innovative and “fastest-moving company in the category.” Based on that, we agreed that a coined, inventive name was the right direction. We built matrices of naming components, including prefixes and suffixes that communicated accuracy, speed, and flow; word parts that spoke to the company’s talent and recruiting; and a set of Greek, Latin, and Sanskrit words that meant reliability and power. And using our proprietary sound-symbolism software, we identified fast-sounding letters.

Drawing from these components, we combined 55 prefixes and 102 suffixes and got about 60 interesting ideas—not solutions; not yet. We repeated the steps three times over two weeks. “Vercel” rose to the top with a sound that is alive and daring, six letters, familiar parts assembled in a unique way.

What not to do

Here are a few things that we have learned not to do over four decades of naming: