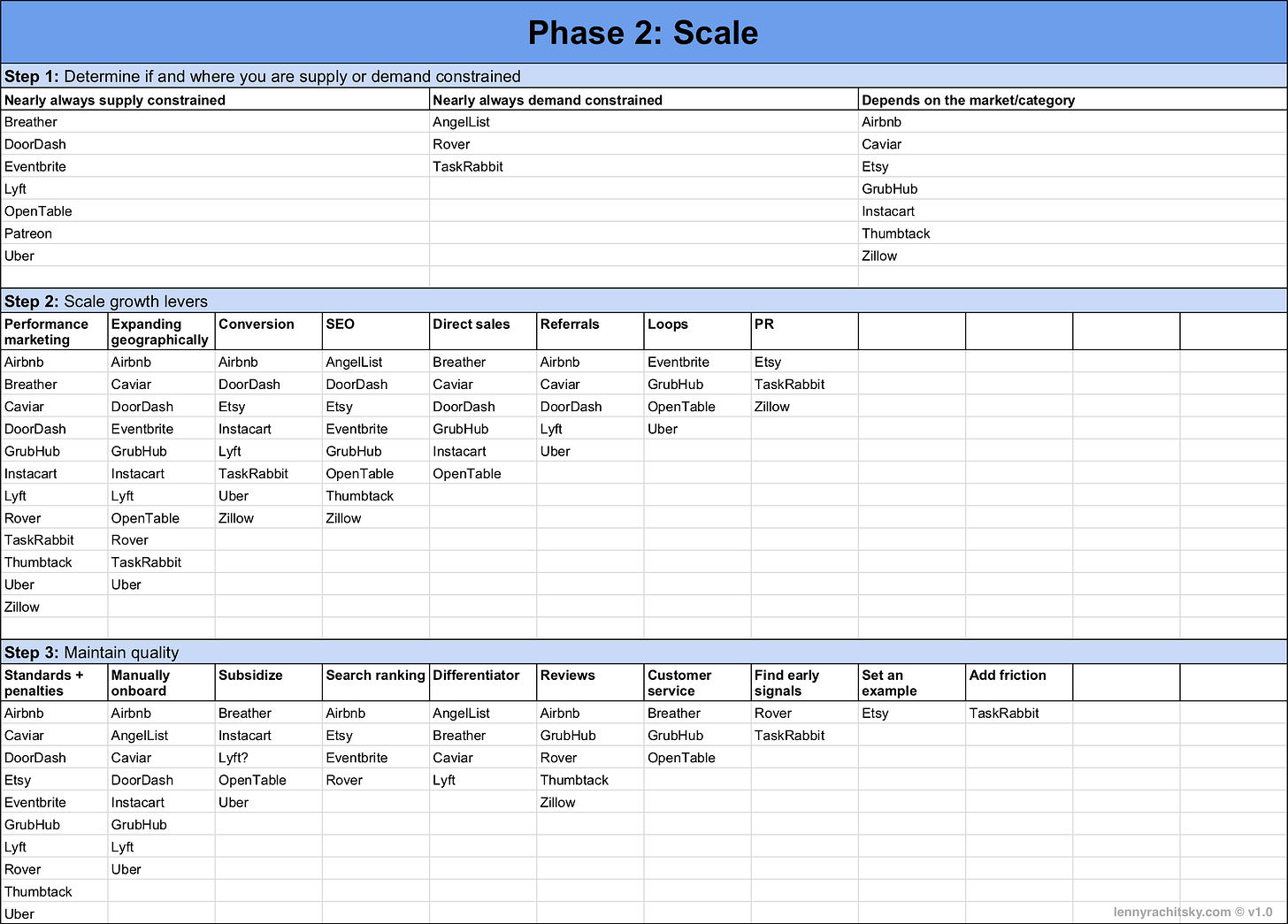

How To Know If You're Supply or Demand Constrained 🤹♂️ - Phase 2 of Kickstarting and Scaling a Marketplace Business

Insights from today's biggest marketplaces, including Airbnb, DoorDash, Thumbtack, Etsy, Uber and many more

“Lyft was always supply constrained. It was obvious to everyone. You open up the app on a Friday night and there were no cars available. Instead, you got a Lyft message saying sorry, try again later. We eventually ended up having to build a waitlist for supply to catch up to demand.

This was especially bad for us because Lyft focused on being reliable — a ride when you need one, with the tap of a button. The aha moment, or inflection point, was a 3 minutes ETA. Under 3 minutes felt instantaneous. When it was over 3 minutes, you were incentivized to shop around, take the bus, walk, or take another ride sharing company. This goal gave our local teams a north star. We found this number by looking at the data – app open to ride conversion, and long-term retention. We saw an inflection point there. At 3 minutes, saw the curve inflect.”

— Benjamin Lauzier (ex-Product Lead for Driver at Lyft)

Welcome to Phase 2 of our series on marketplace growth — Scaling Your Marketplace 🎉 This phase will address the four questions I’m most frequently asked by post-PMF marketplace companies:

Part 1: How do I know if I’m supply or demand constrained? 🤹♂️ (this post)

Part 2: How do I accelerate growth at scale? 🔥

Part 3: How do I maintain quality in my marketplace? 🏅

Part 4: What would you do differently if you could do it again? 🔮

Again, thank you to everyone who has sent me encouragement, new insights, and suggestions for future posts — keep them coming! And for those of you tired of posts about marketplaces 🤷♂️, I’ll soon go back to tackling your questions about building product, driving growth, or anything else stressing you out at the office (an example), after these four posts are out. And, finally, early next year I’ll share the remaining portion of this series, Phase 3: Evolving Your Marketplace 🐛 (*cough* still working on it *cough*)

If you are new to this series, do yourself a favor and check out Phase 1: Cracking the chicken-and-egg problem:

Enough BS, let’s dive in!

Phase 2: Scale your marketplace 📈

At some point, if enough pieces fall in place and the flywheel starts to whirl, you’ll begin to realize that maybe, just maybe, you’ve got a real working marketplace on your hands. Congrats! Nice work. Enjoy this moment — very few companies get this far.

Around this time, you will also begin to find that your early tactics and assumptions become increasingly less effective. Is your marketplace still supply-constrained — maybe it’s demand constrained now? Should you keep building out a sales force, or focus on productizing everything? How do you maintain the high-quality experience your customers have come to rely on as you scale? These are some of the questions I’m most frequently asked by teams at marketplaces that are starting to scale up. And, as it happens, these are the same questions we’ll explore over the next few posts — starting with how to determine if you are supply or demand constrained 🤹♂️

Before we dive in — how do you know when it’s time to “scale”? It’s rarely a binary decision, but few signals to look for:

You believe that you have PMF. Again, read this and listen to this for excellent advice on this topic. A simple heuristic is that retention and growth are healthy in your early geo/category.

You have a strong hypothesis for how to launch a new market or category.

There is a strong competitive threat and you need to respond.

Step 1: Determine if you are supply or demand constrained 🤹♂️

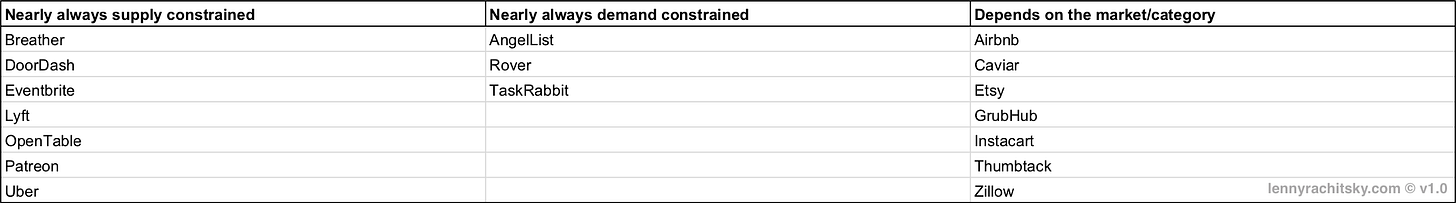

Unlike Phase 1, where 80% of the companies I looked at focused on supply growth almost exclusively, the story quickly gets more complicated as you scale. Though many marketplaces continued to stay supply-constrained indefinitely (e.g. Uber/Lyft, OpenTable, DoorDash), an equal amount saw different supply vs. demand imbalances by geography or category.

Side-note: What does being supply-constrained or demand-constrained even mean? It simply means that your biggest constraint to driving additional transactions is a lack of supply (e.g. Airbnb Homes, Uber drivers) or a lack of demand (e.g. Rover dog owners, TaskRabbit customers). In theory, you always want more of both, but in many cases adding more of one side doesn’t actually lead to growth. Your resources are better spent elsewhere.

A very large share of marketplaces are always supply constrained

About 40% of the companies I talked to started off supply-constrained and then continued to be supply-constrained throughout all of their history. For these companies, the ROI of adding new supply greatly outweighed investing in driving new demand. I have a few theories for why it was true for these companies (e.g. difficult of acquiring supply, novelty of experience, strength of PMF), but I don’t see a super-consistent pattern. If you have insights into this, I’d love to hear them.

Uber:

“We didn’t think about supply demand imbalance a lot because we were always supply constrained. This directly led to surge pricing — we eventually decided that our goal should be that less than a certain percentage of trips should be surged in a market (~20% - 30%). The idea is that any market that was over that percentage was under-supplied, and vice versa. This became our rule of thumb. We always thought about, from a user experience, what level of surge before people start to dislike it?”

— Andrew Chen

OpenTable:

“For us, we knew we had to stay with supply. We were able to graph out restaurant penetration (absolute and percentage of market), and overlay diner growth and the percent of reservations we could deliver per restaurant. It was amazing just how similar each market behaved. Our ability to accurately forecast growth and, therefore, wisely invest in each market, was tied to this direct correlation of restaurant penetration to reservation booking volume. And, not surprisingly, the growth curve wasn't linear, but instead exponential as you might expect in a network effects business.”

— Mike Xenakis

DoorDash:

“When we look at growth, it's always one of three things: Selection, Delivery quality, and Affordability. All supply-oriented. So we were essentially always supply constrained. There are times where we feel demand constrained, but it's very rare. When we launch markets our focus is to get to a small, defined number of deliveries per day (for example, 100 deliveries per day), within a relatively defined space, not all of Greater Toronto, for example, but a couple of neighborhoods. When markets hit that level, they “graduate” as a market. We find that if we don't get to that level of deliveries per day in a market relatively quickly, dashers churn and restaurants churn.”

— Micah Moreau

Very few companies are always demand-constrained

On the other side, only three of the companies I looked at were always demand-constrained at scale.

Rover:

“For us, the scarce resource was demand. I don’t think we were ever supply constrained. Supply was easy. It was the dynamics of the market -- if you are someone who loves dogs, you work from home, you are in a situation where an extra $50 is meaningful, why wouldn’t you sit on Rover? It’s a no-brainer. Demand was much harder because we had to change customer behavior. We had to convince someone to get over the hump of letting a stranger watch their dog -- similar to Airbnb.”

— David Rosenthal

TaskRabbit:

“TaskRabbit was never supply constrained. We had thousands of people on our waitlist to provide services, but the demand-side was more challenging. Over time we actually ended up charging new supply an application fee to reduce the volume of applications, and to increase the quality, while managing our costs to process background checks and other onboarding costs.”

— Brian Rothenberg

AngelList:

“When we pivoted to syndicates we became LP-constrained.”

— Babak Nivi

And finally, and most interestingly, nearly half of marketplaces had varying levels of supply vs. demand imbalance

About 40% of marketplaces I looked at had differing levels of supply vs. demand imbalance across geography and/or category. In some places these marketplaces were supply-constrained, and in others demand. To address this, these companies developed models or heuristics to help them understand which side needed their focus. Though never perfect, and constantly evolving, these models were instrumental in helping them focus their resources.

GrubHub:

“We created a model that looked at restaurant coverage in a market to tell us which markets were supply constrained: (1) What % of restaurants in a market are on GrubHub vs. not, and (2) the number of orders per GrubHub restaurant. If orders per restaurant in that area were in the higher percentiles, we focused on supply in those markets.”

— Casey Winters

Thumbtack:

“We went through a process to find a metric what was most predictive of consumer satisfaction (NPS in out case), and found that ‘Hire Rate’ was directly correlated with the NPS score they ended up giving later. So we focused on Hire Rate. We found that customers were happy when they got at least three results when searching for a Pro, and that we were healthy when 60% of the search results included 3 or more quotes. Below that meant we were supply constrained.”

— Sander Daniels

Airbnb:

“To determine if we were supply or demand constrained in a market, initially we used occupancy rate — if it was above a certain % we were supply constrained. Then, we moved to a model where we looked at occupancy rate vs. bookings rate, and when there was a downward inflection point we knew what occupancy rate that market was supply constrained at. Most recently, we use an econometrics model that tells you for each market — do you get more incremental revenue from one additional unit of supply or demand.”

— Lenny Rachitsky

Zillow:

“To track supply and demand and figure out where we were constrained, we would watch the marketplace health stats like quotes per loan request, loan requests per user, competitiveness of rates, and contact rates by market/area. If we were low in a given area, we would work hard to build supply in those areas or turn down demand.”

— Nate Moch

Instacart:

“The goal for a marketplace is to invest in a supply-demand balance. So you're always investing in both. One metric we use is called Availability. When Availability is high, it means customers can order for immediate delivery. We worked hard to make sure availability is high so that customers are able to order and get value from our service immediately after they sign up.”

— Max Mullen

With a renewed sense of which side of the marketplace to concentrate on, the next question will naturally be “How do I scale and accelerate growth for my marketplace?” Lucky you, that’s the very topic of our next post. Stay tuned!

Overview

Phase 1: Crack the chicken-and-egg problem 🐣

Phase 2: Scale your marketplace 📈

Part 1: Determine if you are supply or demand constrained 🤹♂️ (this post)

Part 4: What would you have done differently if you did it again 🔮