How to spot a top 1% startup early

Three key lessons from people who picked multiple iconic companies before they were obvious

👋 Hey there, I’m Lenny. Each week, I tackle reader questions about building product, driving growth, and accelerating your career. For more: Lennybot | Lenny’s Podcast | How I AI | Lenny’s Reads | AI/PM courses | Public speaking course

Annual subscribers get a free year of 19 premium products: Lovable, Replit, Gamma, n8n, Bolt, Devin, PostHog, Linear, Wispr Flow, Descript, Superhuman, Granola, Warp, Perplexity, Raycast, Magic Patterns, Mobbin, ChatPRD + Stripe Atlas (while supplies last). Subscribe now.

After reading the early draft of this post, my approach to investing and giving career advice immediately shifted. Thank you, Bob, Cristina, Soleio, Rasmus, and Sean, for sharing your incredible insights with us 🙏

For more from Terrence Rohan (i.e. one of my absolute favorite seed investors), find him on X and LinkedIn. Also, don’t miss his previous beloved guest post: Raising a seed round 101.

P.S. You can listen to this post in convenient podcast form: Spotify / Apple / YouTube.

There are endless posts and podcasts about how investors pick startups. But Lenny and I were curious about a quiet class of employees who seem just as good as—if not better than—the most famous VCs at spotting generational companies before they blow up.

How do these rare folks keep joining world-changing companies before most of the world even notices them?

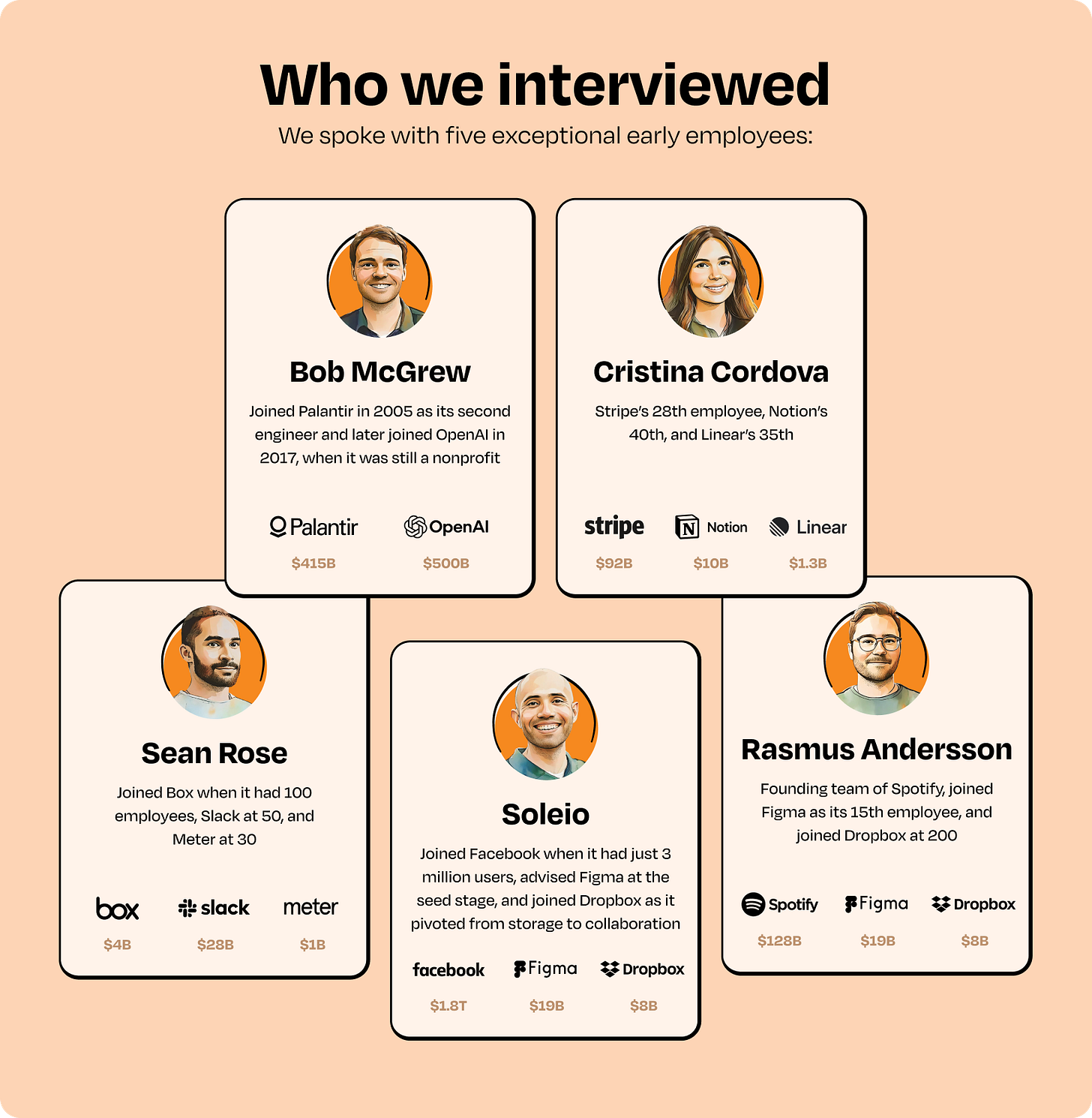

To find out, we interviewed five people whose resumes include some of Silicon Valley’s most remarkable companies: Palantir, OpenAI, Facebook, Stripe, Linear, Figma, Notion, Slack, Box, Spotify, and Dropbox.

Each joined at least two of these companies early—an extraordinary feat, especially since they committed as full-time employees, not diversified investors. Their “hit rate” is phenomenal.

We were curious: What did they see? How did they choose? Are there lessons to take from their experiences?

Across their stories, we saw three distinct factors that mattered most.

Though originally written for job seekers, these insights apply much more broadly—for founders, investors, or anyone trying to recognize greatness early.

Here’s what to look for.

1. Ambition bordering on “ludicrous”

This was the most novel takeaway for us: One of the clearest markers of a future generational company, according to our interviewees, is ambition. It came up again and again.

Bob pointed out that “both Palantir and OpenAI were considered ludicrous when the companies were first started. Joining Palantir in particular seemed like a very risky proposition. But actually it wasn’t risky at all. If the company failed, at worst, I’d wasted a year of my life and would have to go back to my PhD. But if the company succeeded, it would be life-changing.”

Soleio “was surprised by the ferocity and ambition of the early Facebook team. They all seemed too smart to be working on ‘social networking’ but had a lofty idea for where the internet was ultimately headed and how Facebook might completely reshape it.”

Sean added, “If a company’s thesis is marked by extraordinary ambition, it’s probably worth paying attention.”

“The key tell,” Bob said, “was always the ambition of the goal.”

Rasmus explained, “The logic here is simple: If everyone says, ‘Yes, that’s clearly a great idea, and you have direct competitors on day one, you are definitely late to the game. Even if you excel and go above and beyond expectations, the chance of making a meaningful difference in this world is small-ish. However, if someone has sailed across the sea of exploration, waded through the bog of research, and is still going on about an idea, there’s a small chance that they are ahead of the rest of us and see something I’ve yet to see.”

How to judge ambition

What are signs that the founder’s ambition is big enough?

The founder sounds a bit crazy. Sean shared, “For Meter, to start from scratch to make your own hardware across many platforms . . . it really indicated that this company is taking a huge swing. Or they’re just crazy. Along those same lines, when I met Dylan Field [CEO and co-founder of Figma] on a bus to a developer conference in 2013, he was just starting Figma. I remember talking to him about what he was building, what he wanted to do with it, and how it seemed completely insane to do in the browser. It was clear Dylan was not going to stop, no matter what, and we know how that has gone.”

People laugh at them. Rasmus recalled, “Spotify, a little group of ‘nobodies’ in Sweden, said, ‘Let’s build a catalog of all the music in the world and give everyone access.’ People laughed at us—I mean that literally, as in record-label officials laughing at Daniel [Ek, CEO and co-founder], asking them to give us a chance. The key here was that businesspeople thought it was a bad, bonkers idea while friends thought it sounded like a perfect future.”

No one has ever attempted this idea before. Rasmus added, “It may be a bit of a cliché at this point, but if no one else is trying to do what a company is trying to change in this world, then there might be something interesting going on, especially if it’s ambitious.”

To close, in the words of Bob, “At one point at Palantir, [co-founder and CEO Alex] Karp said, ‘We want Palantir to be the most important company in the world, not the most valuable one. But if it’s really important, it’s going to be valuable too.’”

2. Founders, founders, founders

Building on the above insight, every interviewee emphasized the same point: the founders matter above all else. Not as one variable among many—this was the variable.

Cristina (early Stripe, Notion, Linear) said it outright: “The founders (and early team)—nothing matters more than this to me. I’m going to work hard, and I want to win, but I want to do it with people whom I want to see win too. When I joined Stripe, I joined more because I thought the people were special. I had more conviction about the company itself later.”

Sean (early Slack, Box, Meter) echoed her: “Quality (and authenticity) of founders have always been the most important variable to me.”

Rasmus (early Spotify, Figma, Dropbox) distilled it even further: “People and mission. Who and why (not as much ‘how’).”

Bob (early Palantir, OpenAI) added, “The common pattern was an incredibly ambitious goal combined with a credible team.” There’s that ambition again.

How to judge founders

Joining a company with great founders is easy to say and hard to do. What exactly makes a founder great? Many people call out intelligence, and we have a whole section highlighting the importance of ambition. But our interviewees mentioned some less obvious traits.

1. Ability to adapt

Bob pointed out that “both Palantir and OpenAI started with an unworkable initial strategy that perhaps the world was correct to mock. But both iterated over time to something that worked. It’s more important to be able to learn quickly than to have a good strategy.”

Cristina shared the same sentiment: “It’s so difficult to build a company, and there’s so much you need to learn going from one stage to the next and scaling. Founders who truly love to learn and look at company-building as a learning experience are quite predictive of whether founders will build durable, special companies. I remember saying early on at Stripe that Patrick and John [Collison, co-founders] didn’t just want to build a great product; they wanted to build a great company. And in looking back, I remember their apartment had books piled to the ceiling—they knew so much about so many different topics, and they always sought advice from others. They had a learning mindset, and I think they still do.”

Sean described this as “rate of change.” Soleio called it “clock speed,” adding, “The common thread I’ve observed with all of these companies is how fast they operated and how extraordinarily capable their early employees were. Are they building their ideas in real time or does it take months to see their visions crystallize in software?”

2. Ferocity

Rasmus looked for “clear passion from the people who are ‘the company.’ Passionate and interesting people have been a core aspect of my professional life.”

Cristina said she “loved Ivan’s [Zhao, founder and CEO of Notion] intensity” and has always been drawn to “intensity plus intelligence.”

And as you’ll recall from above, Soleio “was surprised by the ferocity and ambition of the early Facebook team.”

3. Founder-market fit

Sean always asked himself, “Do these people seem like they’re doing what they’re meant to be doing, and is there no question that no one else can do it as well as them?”

Bob was optimistic about Palantir’s chances because “it was founded to take the ideas behind the analysis software that solved fraud at PayPal and apply them to the intelligence community.”

To close, in the words of Cristina: “If the three most important things in real estate are location, location, location, the three most important things in startups are people, people, people.”

3. Judging today’s product is a trap

You’d think that for legendary product companies like Stripe, Figma, Slack, Notion, and Facebook, you could tell how special they were going to be by how good their early product was. It turns out this way of thinking is a trap.

Soleio said that when he first logged in to Facebook, “I remember being disappointed. The version their team had described was light-years ahead of what I saw that day.” Likewise, Figma was more prototype than product the day Dylan laid out his vision to me for building a collaborative design platform.”

Cristina had a similar perspective: “Many of the companies I’ve joined were developer products or products that were meant for teams, so I couldn’t truly try the product myself, as I’m not a developer or didn’t have a team use case for it. So in general, I discount my own thoughts about a product in those cases.”

Sean told us that “in the earliest days of Slack, it was rough around the edges. To quote Stewart [Butterfield, co-founder], it was a giant piece of shit. The bulk of the vision was there in that beta period from 2013 to 2014, but still awaiting refinement.”

Rasmus rightly pointed out, “Almost every product I’ve worked on started out as one thing but was something quite different at the time of consumer success. Spotify was going to be a video streaming platform and Figma a meme generator.” So even if the product is great, it may have to radically change anyway.