Introducing the GAIN framework for feedback: an evidence-based approach to giving feedback that people love, appreciate, and act on

A step-by-step guide to crafting feedback you’ll want to give and people will want to get

👋 Hey there, I’m Lenny. Each week, I tackle reader questions about building product, driving growth, and accelerating your career. For more: Lennybot | Lenny’s Podcast | How I AI | Lenny’s Reads | Courses

Annual subscribers get a free year of 15+ premium products: Lovable, Replit, Bolt, n8n, Wispr Flow, Descript, Linear, Gamma, Superhuman, Granola, Warp, Perplexity, Raycast, Magic Patterns, Mobbin, and ChatPRD (while supplies last). Subscribe now.

If feedback is a gift, why is it so hard to receive? And to give.

It’s because no one taught us how to give feedback.

I was introduced to Jack Cohen by (frequent collaborator) Tal Raviv, who told me, “Jack is the single biggest influence on my personal productivity and ‘inner game.’ ” Over the past 11 years, Jack has coached hundreds of founders, executives, and managers to help them grow themselves and their colleagues as fast as their startups.

Growth hinges on getting honest and ongoing feedback. Through thousands of feedback conversations and hundreds of hours of research, Jack’s developed an evidence-based, immediately applicable framework for giving feedback that he calls GAIN. As Jack puts it, “GAIN is both a useful acronym and the core of the philosophy.” When you tell people what they stand to gain from the feedback, it suddenly starts feeling like a gift again.

This guide is essentially a how-to for Radical Candor, and the most specific (and easy-to-remember) framework for giving great feedback that you’ll find anywhere. It’s going to blow your mind. Enjoy.

For more, Jack teaches a highly rated course, ManagerGPT: The AI Tools and Human Systems to Scale Yourself and Your Team Fast, focused on helping high-growth leaders build their individual operating systems and interpersonal skills to stop fighting fires (or each other) and start creating what matters most: great products and great teams. For a taste of the course and a demo of both GAIN feedback and the AI tool Jack built to support it, check out his free 30-minute lightning lesson, “FeedbackGPT: Give Feedback People Thank You For.”

You can also listen to this post in convenient podcast form: Spotify / Apple / YouTube.

Over my past 11 years coaching several hundred people from dozens of organizations and teaching thousands more, there’s one challenge I’ve seen people struggle with across every level, industry, company stage, personality type, and culture: giving feedback.

Many people come to coaching and workshops already describing themselves as “conflict-averse,” dreading having difficult conversations and giving direct feedback. A good number arrive fed up with failed attempts to get people to change their behavior, with many missing the irony as they bemoan, “I keep giving them the same feedback, and they never change. Maybe they just don’t want to.”

What these folks miss is their own power to catalyze change by shifting the framing and approach of the feedback they give.

I’ve seen and felt firsthand the difference between the “feedback masters” and “feedback disasters.” After every feedback conversation from one colleague who I had initially respected, I felt deflated. As a result, everything suffered: our product, our relationship, and my overall well-being.

Later, I worked with another colleague whose feedback left me elated every time (actually!). I couldn’t wait for meetings with her because I enjoyed them so much and I knew that her feedback would help even my best work reach another level.

On reflection, I realized that the content of the feedback from these two colleagues was strikingly similar, but the way my second colleague framed and delivered hers lifted me up instead of shutting me down.

That difference answered an age-old question: How on earth do you get someone to change or grow? And how can you do that in ways that strengthen your connection instead of breaking it? By mastering the art (and science) of giving great feedback.

The good news is that this is a learnable skill—and one that is core to my work as an executive coach and organizational behavior consultant.

On a daily basis, I give feedback to clients and help them give feedback to their colleagues, as well as establish effective feedback systems across their teams and organizations.

At my company, we also practice this in almost every meeting, and the growth it elicits is remarkable. One colleague said that after regularly getting and giving feedback using the GAIN framework, he felt “much more driven by purpose, rather than by fear.”

So what is the difference between the feedback masters and disasters? How can you shift your framing and approach to ensure that the feedback you offer inspires people to take action and keep growing? My experience, informed by a wealth of research from multiple fields, shows that effective feedback shares several key qualities:

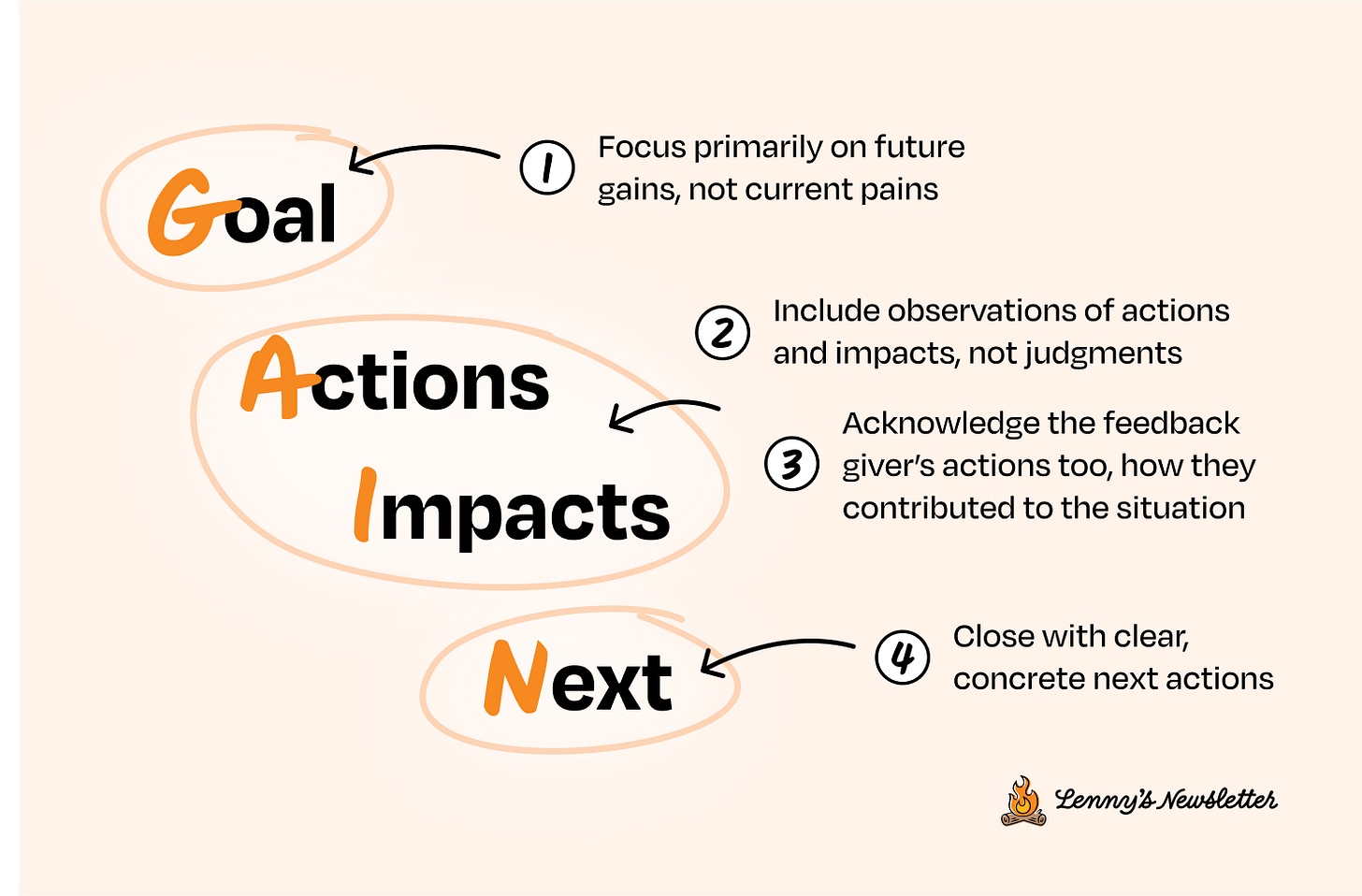

I call this feedback approach the GAIN framework. GAIN is both a useful acronym for remembering these essential ingredients in effective feedback and the core of the philosophy.

It is profoundly more effective and inspiring to frame feedback based on the experiences or results we want to move toward (the gain) instead of focusing only on what we want to move away from (the pain).

We can often do this in just a few short sentences. Say an engineering lead is frustrated with a PM’s sloppy handoffs and the resulting delays. The engineering lead’s feedback to the PM might sound like: “I want us to reduce handoff friction so we can ship faster. The last handoff meeting we had, you didn’t share any background customer research, which I failed to flag at the time. Lacking that context led to multiple rounds of engineers pinging you with questions instead of making empowered decisions on their own. Can you include that next time?”

The challenge is that feedback doesn’t typically show up in our brains in such a crisply articulated, ready-for-prime-time state. It might start as “Product just threw this over the wall; they don’t care about our time.” Or “They’re lazy; they always do this!” It takes some translating to get our raw reactions into a form that’s more likely to have the desired impact (the “gain”). That form must include:

What both parties ultimately care about (the Goal)

What needs to change to get there (the Actions)

Why (the Impacts)

Who will do what by when to start making progress (Next actions)

Thinking through the GAIN elements is a powerful way to understand and channel those raw reactions constructively. This often starts by using your feelings as a clarifying signal pointing to what you really care about, which should inform your Goal for the conversation. In cases where your feelings are particularly strong or unwieldy, preparation that’s even more focused on your “inner game” (a topic for a different post) becomes an essential step in leveraging the GAIN framework.

Especially with complex or sensitive topics, including each of these GAIN elements in the conversation—often, but not always, in order—leads to greater receptivity and, consequently, more behavior change and more satisfying results.

Once my clients understand how GAIN works, they see the ways they themselves have been unintentionally eliciting defensiveness and resistance and how, very practically, they can flip that on its head.

One founder said, “GAIN helped me have structured conversations that have proven to be successful especially with ‘fragile’ team members. I’ve done this successfully with more than five people in just the past two weeks.”

Another client, startup veteran Brian Martin, described his experience this way: “After I gave feedback once or twice in this new way and saw people actually listen and change and drive the business results or the behavior that I was trying to help them toward, I was like, ‘This is great. I can do this.’ It created a positive feedback loop, and now it’s something I just do that I think people really appreciate about me.”

As Brian notes, people start to realize that the function of feedback isn’t just for behavior change. When shared with skill and engaged with vulnerability, a substantive feedback conversation builds immense trust, meaningful connection, and deep gratitude. (For example, many guests on Lenny’s Podcast and beyond rave about that exact impact that Sheryl Sandberg’s feedback had on them and their relationship with her.)

This post will help you build confidence, fluidity, and effectiveness in giving feedback that people end up thanking you for.

I’ll walk through a real scenario from a client who applied the framework within a challenging interpersonal context (with a micromanaging founder), explaining each “move” she makes. Then I’ll review phrases and principles you can use, and wrap up with three ways AI can help you prepare and master feedback.

But first, where did GAIN come from?

Why GAIN? The evidence behind the framework

GAIN represents the convergence of principles that I encountered in research across over a dozen diverse domains, ranging from couples therapy to decision-making to workplace collaboration to teaching, all focused on how to inspire enduring behavior change.

They all orient to the same thesis: Communicating what we all want more of (the gain) is more effective than communicating what we want less of (the pain). They don’t say that speaking about pain is bad, just that it’s helpful to contextualize it as the gap between where we are and where we want to be.

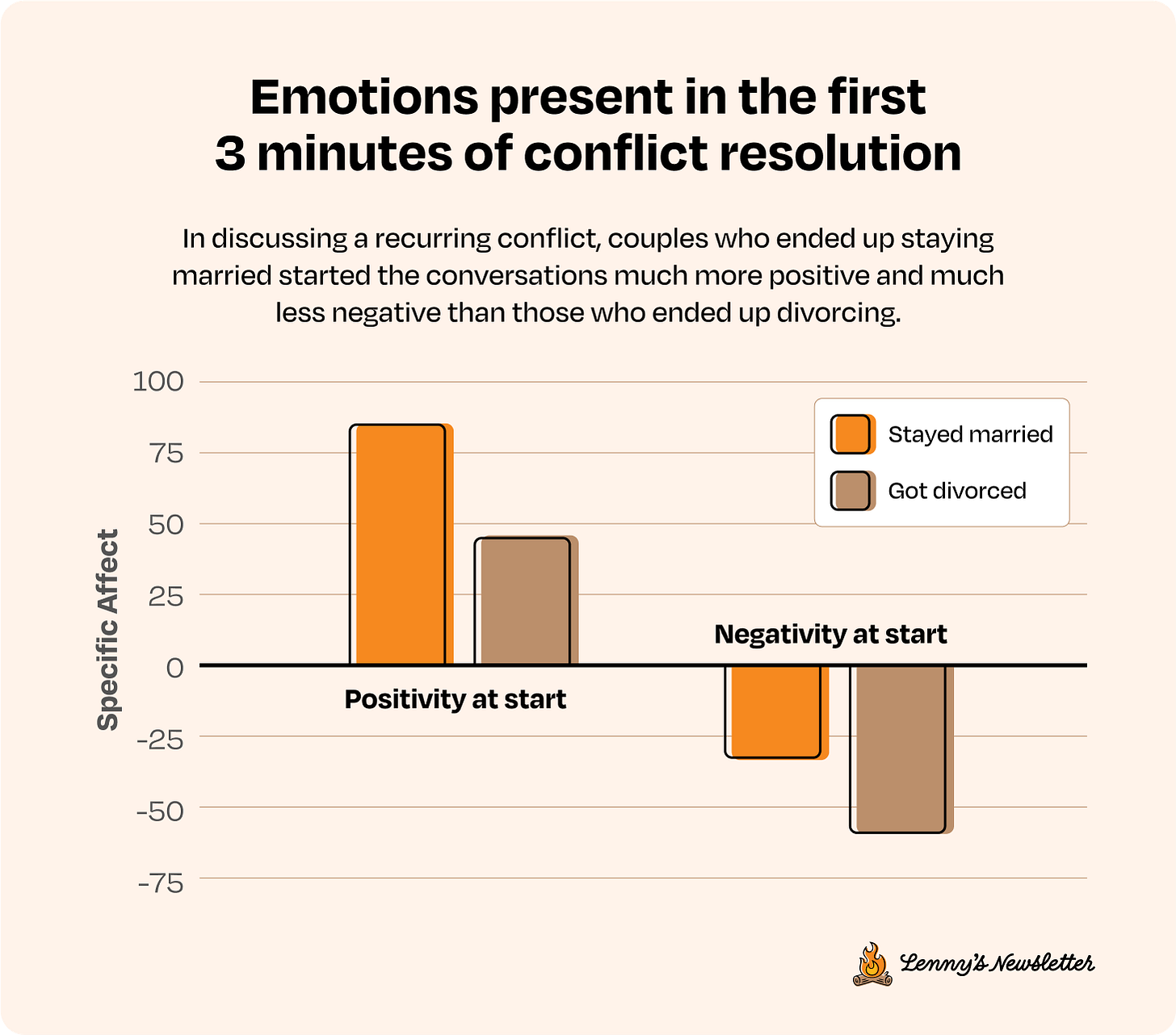

First, let’s look at communication in the most sensitive domain: marriage. Watching just three minutes of a conversation, marriage researcher John Gottman was able to predict with 93% accuracy which couples would be happy, distressed, or divorced six years down the road; most people, even couples therapists, averaged 50% accuracy. How does Gottman distinguish the relationship masters from the disasters? His meticulous research, filming couples’ conflicts and tracking the couples over years, shows that couples with long-term happy, stable relationships open conflict conversations with more positive and less negative emotions than doomed ones, especially focusing on sharing the “dream within the conflict.” Instead of just complaining, they articulate what it is they want more of and why (the Goal in GAIN). Hearing what you both want more of makes it easier to feel motivated and excited about the future rather than frustrated about what’s not working in the present. When 65% of startup failures are attributed to problems within management team dynamics, Gottman’s relationship research is also worth paying attention to at work.

The GAIN framing not only leads to behavior change, it can also elicit better decisions. One study by Amos Tversky and colleagues showed that doctors given data with an avoid framing (“The mortality rate is 10%”) made the most effective treatment decision only 50% of the time, whereas those with the same inputs but using an approach framing (“The survival rate is 90%”) made the most effective decision 84% of the time. The meaning of the framing is identical (10% rate of mortality is the same as 90% rate of survival), but the avoid framing and its threat mindset distort our ability to think and process information clearly. This is precisely the ability we want people to be engaging when receiving feedback and considering a change in behavior.

This dynamic plays out elsewhere in the workplace as well (and in a way I keep thinking about as leaders fret over AI adoption strategies). Amy Edmonson’s research compared teams in 16 different organizations implementing the same new technology. She showed that teams whose leaders pitched it using an “aspirational” framing (e.g. “This will help patients recuperate faster”) were far more effective than those using a “defensive” framing (e.g. “The reason for doing this . . . is to avoid being blindsided by competitive pressures in the future”). The successful leaders not only emphasized what to move toward, they also framed getting there as a team effort.

Our brains are engaged in a constant calculus: approach or avoid, friend or foe? When we frame a conversation with the potential benefits of change and acknowledge what we need to change ourselves, it sends a strong approach signal—a powerful “we’re on the same team” message—to the other party. They are then more likely to hear it as “Hey, this information can be really useful to me, and I want to help this person too.”

To explore what all this theory looks like in a real feedback conversation, see the case of one of my clients below.

GAIN in the real world: Giving feedback to a micromanaging founder

Laura is a VP of Business Development at a high-growth startup, where she reports to a founder who practiced micromanagement like it was her religion. Unsurprisingly, this was quite frustrating for Laura. It would have been tempting to approach this challenge by telling the founder how deflating this experience was and asking her to change (or by just avoiding the conversation altogether, growing resentful over time, and eventually looking for another job). Instead, Laura processed her own raw reaction first, using her emotions to uncover what she actually wanted to get out of a feedback conversation: the founder to give her more space. Laura understood Gottman’s “dream within a conflict” principle, so when the founder was complaining to her yet again about other teams—this time the sales team—Laura seized the moment.

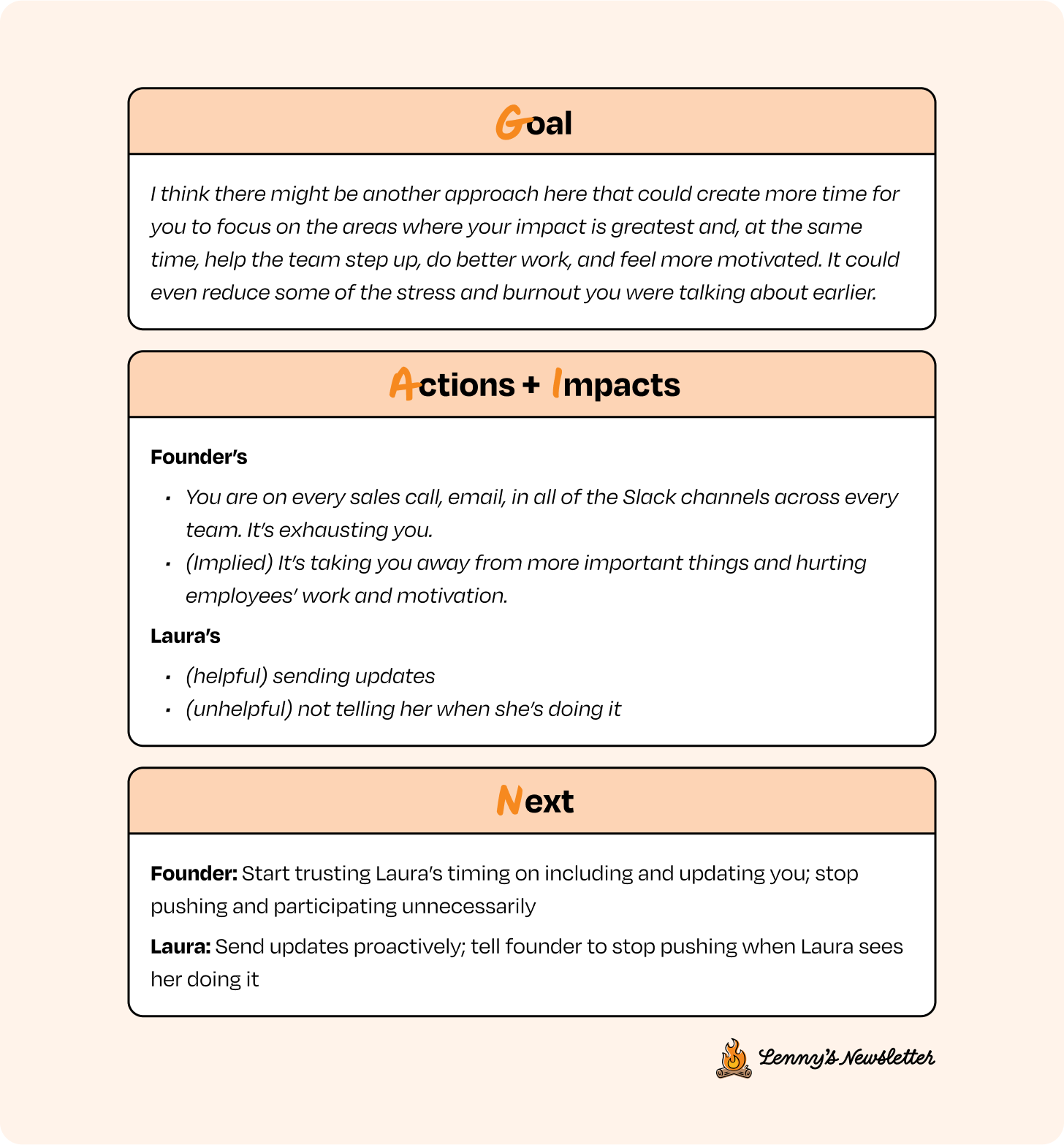

When she began the conversation, she named the founder’s actions and the impacts that mattered to the founder, and empathized with her on those points. Then, instead of dwelling on the founder’s pain or going into her own, Laura turned toward the possible goal for the founder, emphasizing the benefits for the founder in a way that aligned with her own goal. (GAIN conversations don’t have to present the goal first to be effective, as long as they are in the spirit of GAIN and the goal is clarified soon after.) Finally, she guided the conversation toward next actions that would accomplish both of their goals.

Here’s how she masterfully led the conversation, as she reported it to me:

Actions and Impacts: “Right now, I can see you are on every sales call, email, in all of the Slack channels across every team, and I can only imagine how exhausting that must be.

I imagine that you feel like you have to do it because you feel the job won’t get done unless you do.”

Goal: “I think there might be another approach here that could create more time for you to focus on the areas where your impact is greatest and, at the same time, help the team step up, do better work, and feel more motivated. It could even reduce some of the stress and burnout you were talking about.”

The founder responded honestly, “I know, I know, and I want to fix it. But I just don’t see any other way of doing things, and I don’t see the sales team getting the results.”

A feedback opening line is an invitation, and Laura’s was so inviting, the founder accepted and immediately engaged with it. The response, though brief, revealed lots of useful information: the founder’s desire to change, the obstacle to that change, and what matters most to her—getting results. Laura can leverage this to move the dialogue forward toward her desired outcomes.

Next, Laura took her founder’s concern seriously and engaged her further, asking more questions that invite the founder to reflect more deeply on the obstacle she’s raising while emphasizing the importance of trust:

“If that’s the case, do you have the right people? If you can’t trust people to do the work, are they the right people?”

“Yeah,” the founder said, “I think that’s the bigger question—the thing I need to think about.”

Having built a sense of “I’m on your team” in the conversation, Laura continued and challenged her:

“The interesting thing is, though, I know you trust me a lot—you’ve mentioned it, and I’ve even observed it—but you still sometimes do it with me.”

Here, Laura doesn’t judge or criticize; she just references her observation of the founder’s pattern of actions (participating in all calls, emails, Slack channels), as well as the exceptions to that pattern (“You’ve mentioned [your trust in me], and I’ve even observed it”).

The founder acknowledged, “I know. It’s just my way; I’m so used to doing it. I get everything done myself. I push, push, push.”

So Laura asked, “What would be more helpful for you, so you don’t have to do that?”

Instead of solely focusing on what the founder can do differently, Laura’s question broadens the possible levers for change to include herself and others. Some people are wary that this approach might mean less accountability for the feedback recipient, letting them off the hook. Rather, more levers means more leverage to get what we want.

Next actions: The founder replied, “I really appreciate when you proactively send me updates—which I know you already do. But also, you can just tell me when I’m doing it.”

Laura confirmed: “Sounds great. So moving forward, I’ll continue proactively sending you updates, you’ll work on stepping back—i.e. not jumping in or pinging me with status checks—and I’ll name it in the moment if the old pattern rears its head.”

These are clear, concrete actions that they can both take to change the feedback recipient’s pattern of checking in unnecessarily. The founder conveyed her intent to stop while also acknowledging her imperfection and inviting Laura to help her make this change—which was particularly empowering given the power dynamic.

The improvement took time to sink in, though Laura felt full agency to help move it forward. A month later, she shared that the founder had reverted to micromanagement mode three times that week, but then stopped after Laura told her when she would send an update. Over time, the micromanaging pattern ceased almost completely, and not only that; Laura told me that she felt newly confident in her ability to initiate challenging conversations.

Laura navigated a tough dynamic with someone holding greater organizational power and emerged with both the founder’s commitment to change and an invitation to support that change—while building her own confidence and skills.

GAIN feedback principles and phrases

This example models both the practical steps of the GAIN framework and the spirit of it: care and challenge, offering empathy and expressing what the feedback giver wants—in that order.

Here’s a simple breakdown of Laura’s conversation through the lens of GAIN, though her goal comes in the third sentence, not the first:

You can download the GAIN template here, with prompts to guide you.

Let’s dive into the nuances and some helpful phrases and principles you can consider, drawing on Laura’s example and others.

G: The Goal

The essence of the Goal section is naming the topic and pointing to the possible benefits of making a change in such a way that they feel you’re on their team.

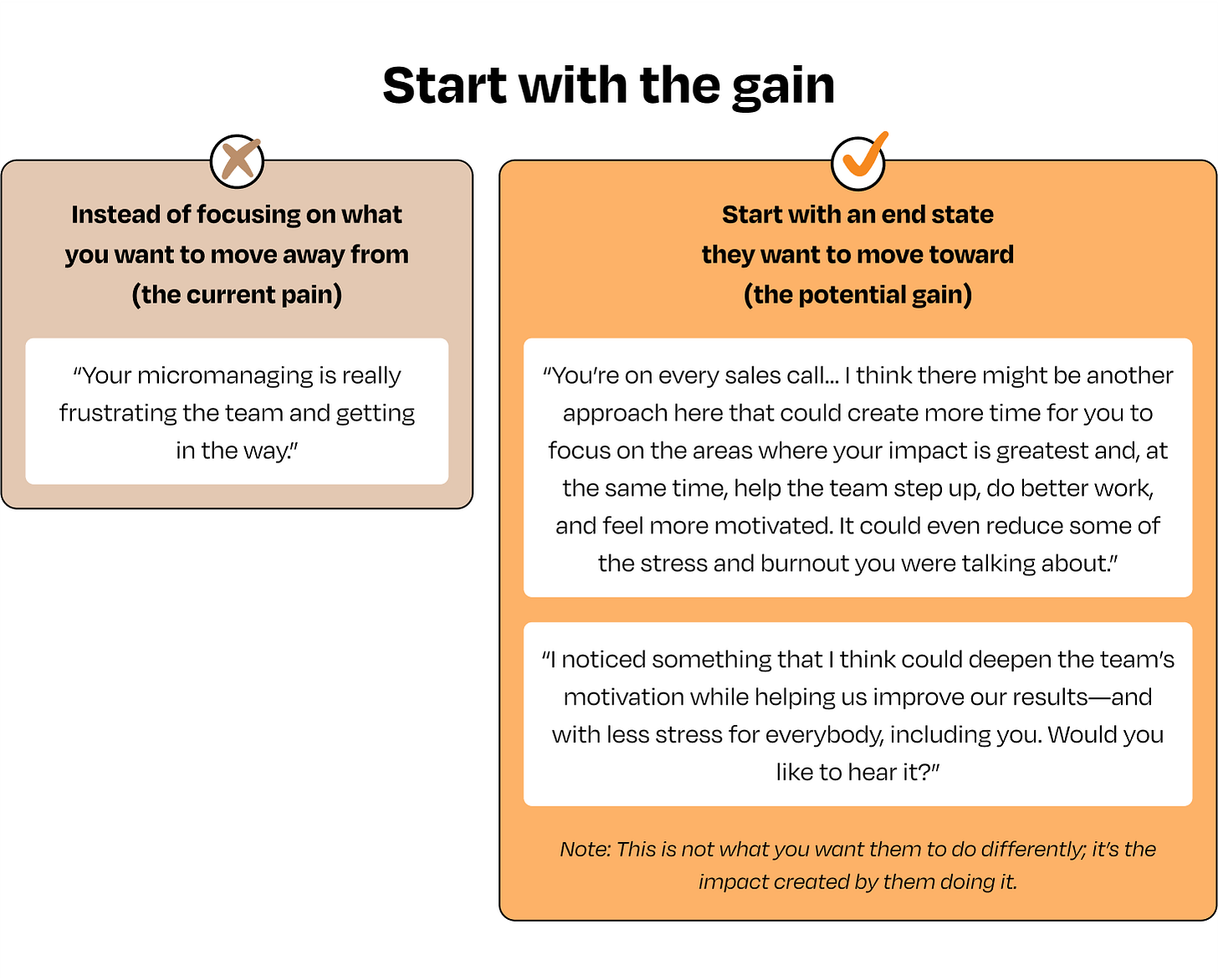

These benefits can be for you too, but they must be appealing to the feedback recipient. This is not what you want them to do differently; it’s the impact created by them doing it. What will they gain from making a change?

If they understand that motivation up front, they’re hooked, and everything else flows from there.

What struck me most in the way Laura shared her feedback is that it didn’t sound like a complaint or criticism at all. Instead, she shared it in a way that genuinely came across as a desirable opportunity for both the founder and her. She mentioned the current pain but oriented to the possible gain, “the dream within the conflict” that Gottman’s research showed to be so effective.

Here are a few ways to approach this.

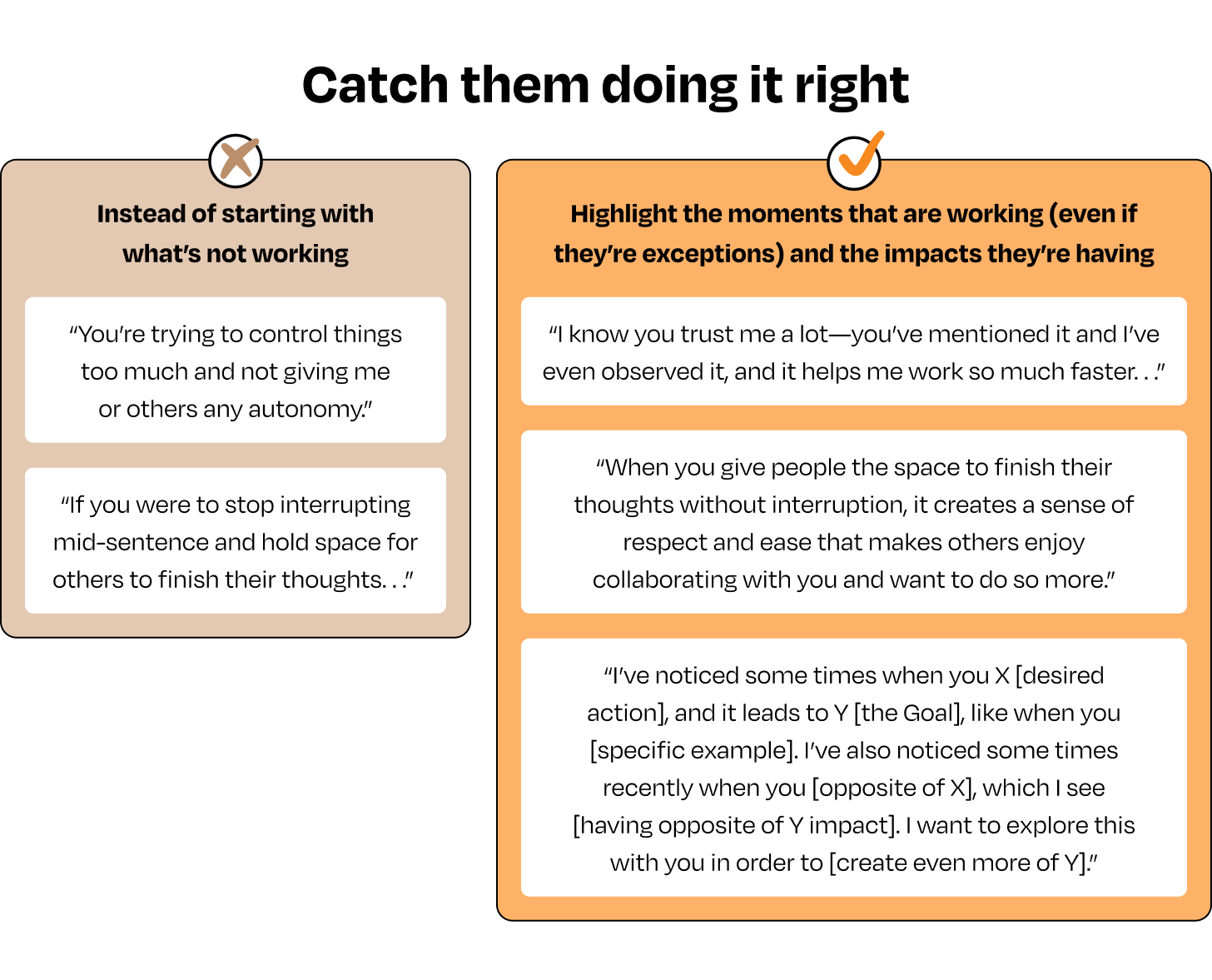

If you can find even one instance of someone already using the desired behavior, it will help them recognize what that looks and feels like. Further, they will feel more confident in their ability to act in that way. The impact of that behavior serves as the Goal for the feedback.

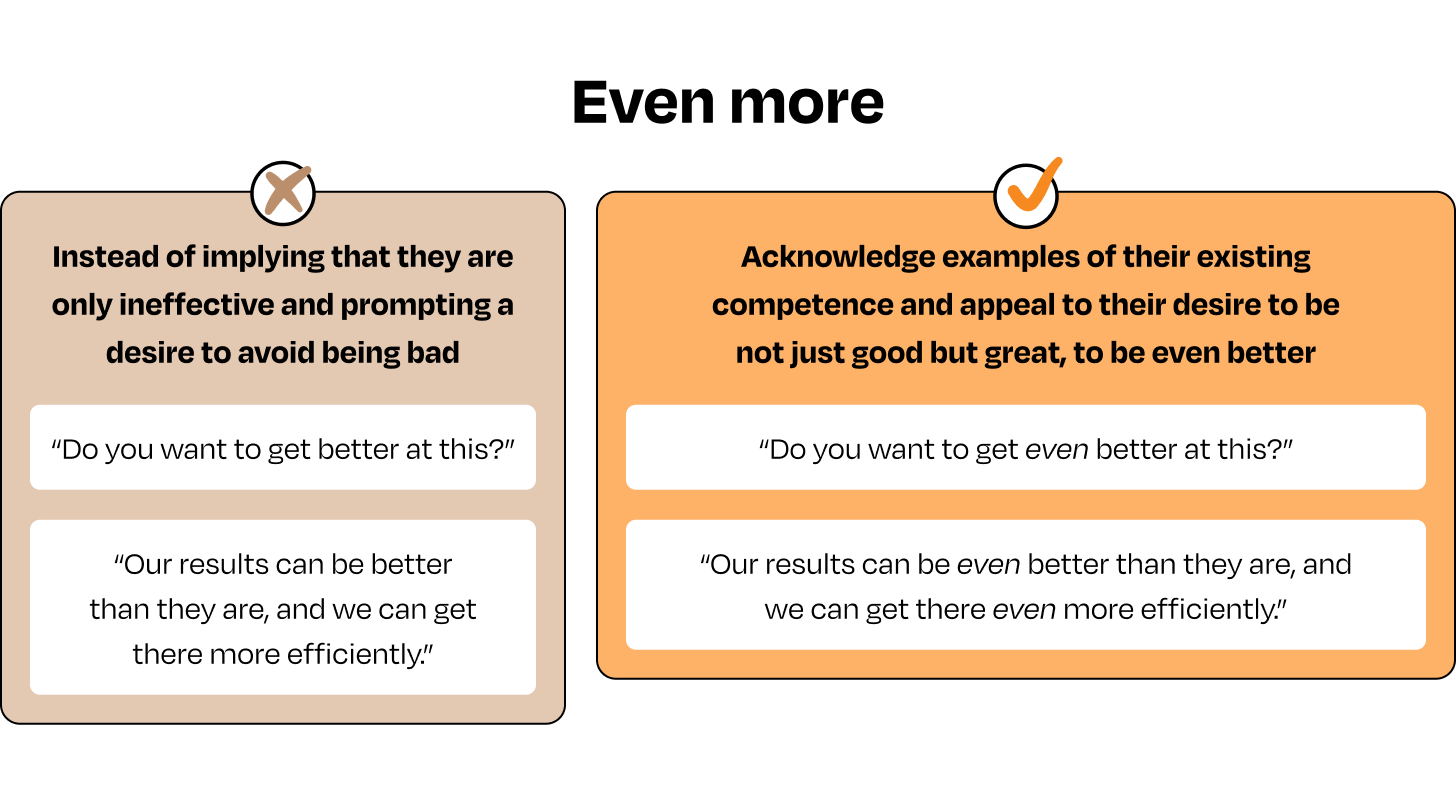

“Even more” conveys that they both have some foundations to build on and that they’re not there yet.

Sometimes it’s important to emphasize the “not yet,” the gap between where performance is now and where it needs to be. In those cases, we must offer both challenge and support. These qualities are usually understood as opposites (“I’m either extremely honest or extremely caring”), but that is a misconception.

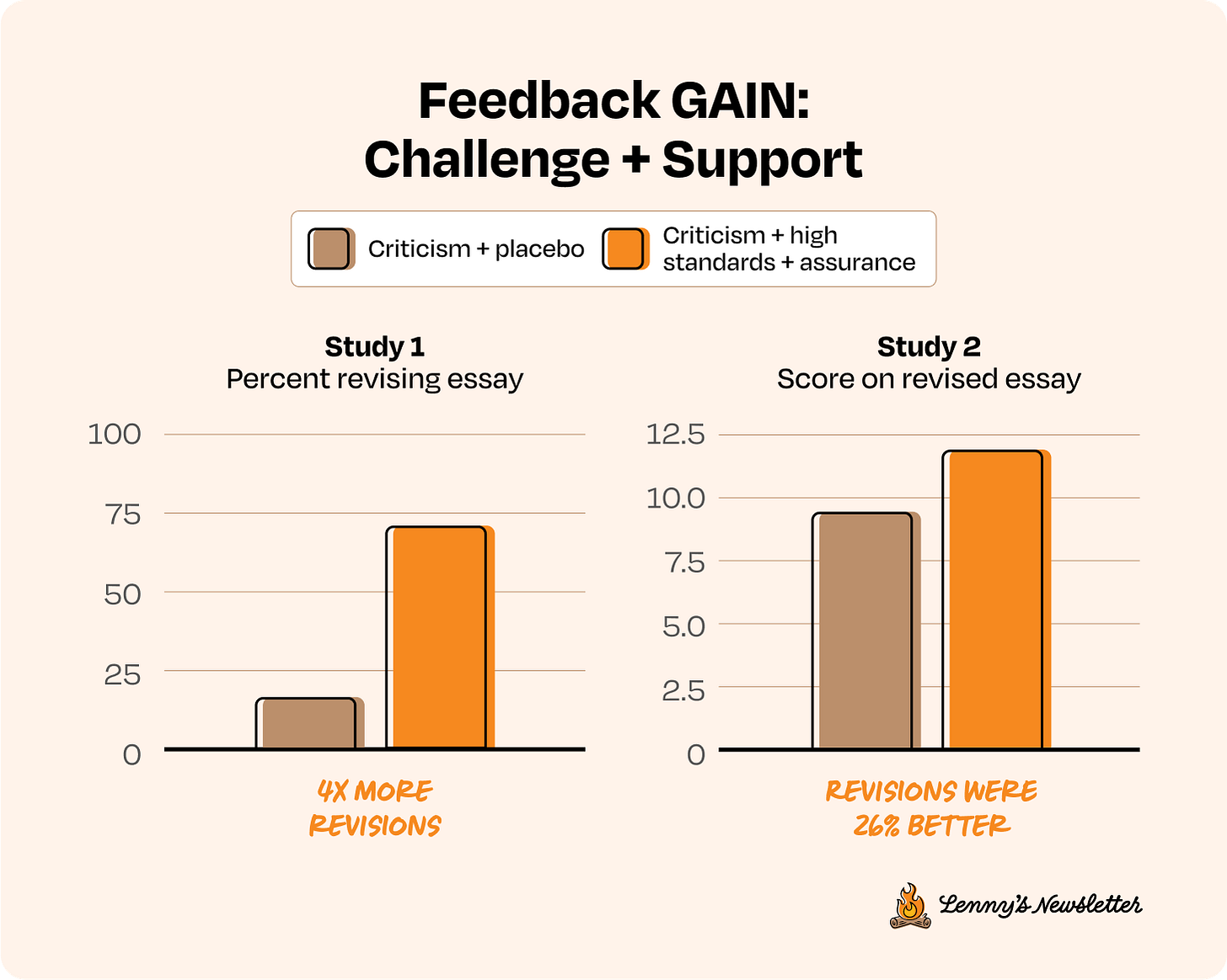

One randomized, double-blind controlled study from Stanford tested the impact of integrating these two qualities using the sentence “I’m giving you these comments because I have very high expectations [challenge] and I know that you can reach them [support].” Compared with a placebo—“I’m giving you these comments so that you’ll have feedback on your paper”—the first sentence more than quadrupled the number of revisions to the original work that one group of students did, and the revisions themselves were on average 26% better.

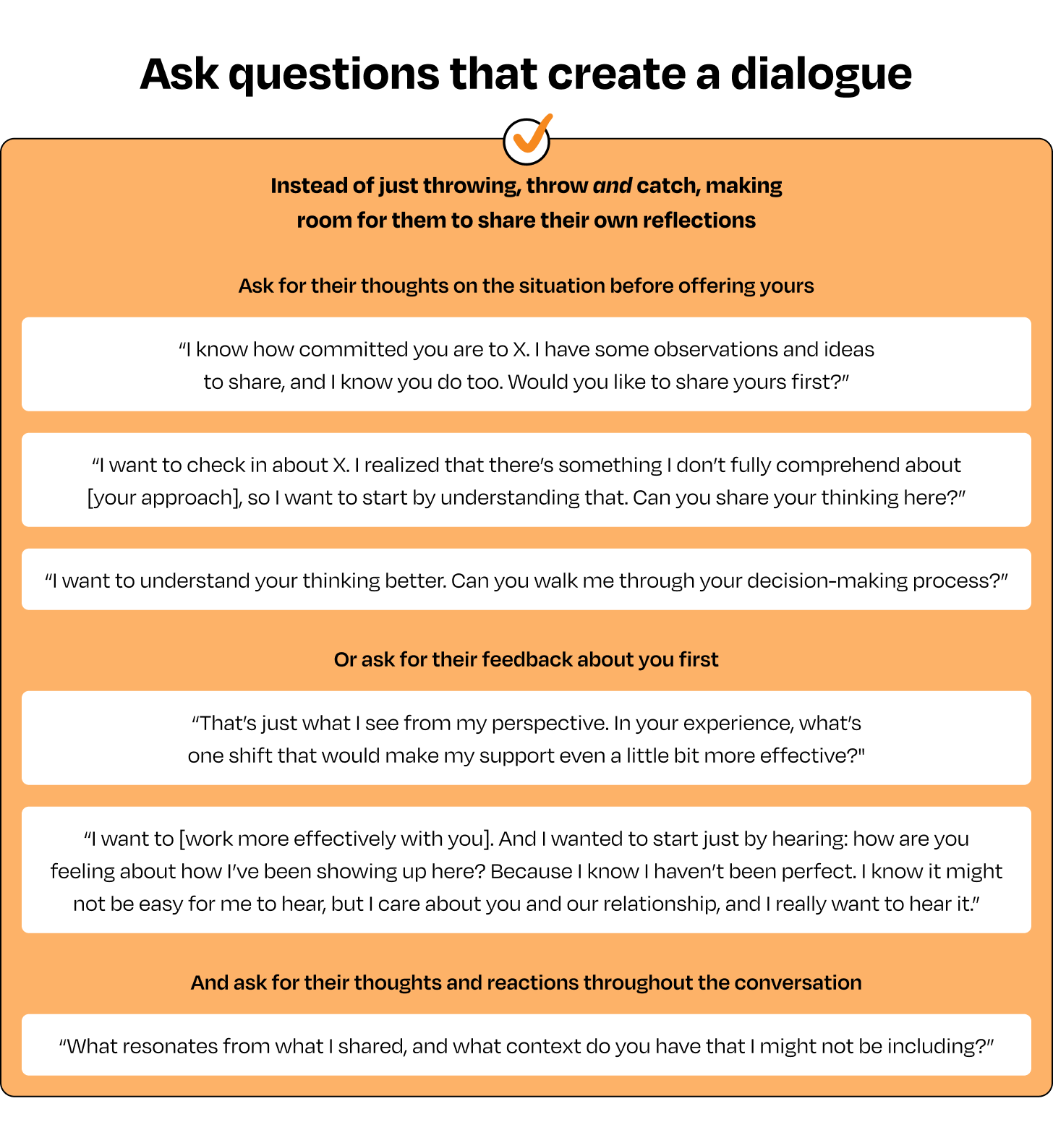

Each of the phrases above can engage people’s interest in the conversation, but the key is that it be an actual conversation—a dialogue, not a monologue. One of the most common mistakes I see people make is delivering feedback instead of exploring it together.

The point is not you giving the feedback; it’s them getting it—and ideally, you getting some insights too. In this way, communication is like a game of catch: the other person needs to actually receive and hear the feedback in order for the game to be successful. GAIN largely focuses on throwing better so it’s easier for them to catch whatever you’re throwing, but ultimately, effective communication is an alternating rhythm of throwing and catching.

You can initiate this rhythm by pausing routinely and asking a question that elicits their reflections, reactions, and their own feedback for you. This creates two benefits: (1) it can reveal what message they are actually getting, giving you the opportunity to clarify immediately if needed, and (2), equally important, it can expand your understanding of root causes, revealing blind spots you may have (and keeping you from putting your foot in your mouth).

Especially if you’re not clear yet on why they would care or what their goal is, listen before you talk.

A & I: Actions & Impacts

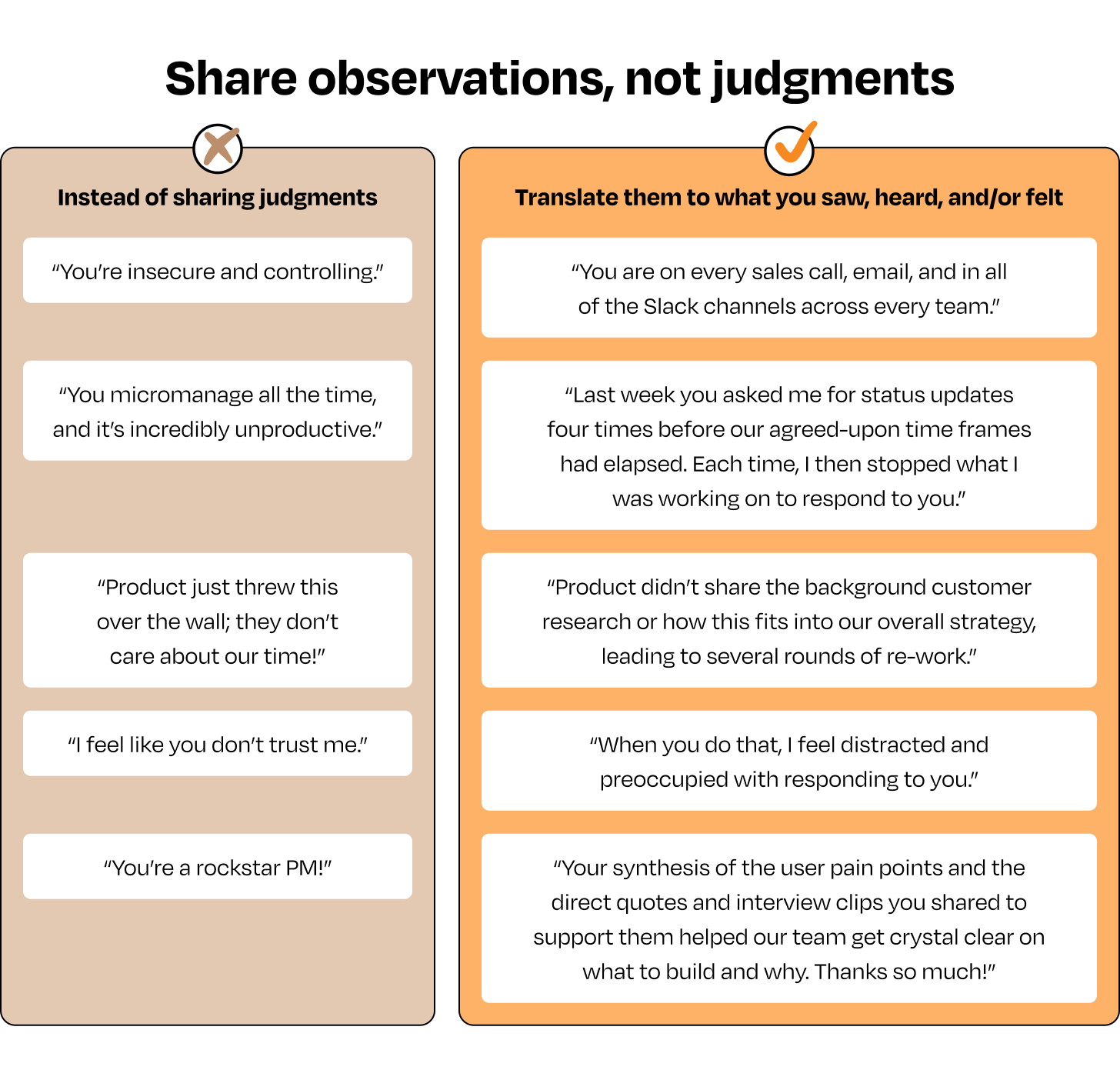

It’s not just the goal that determines receptivity or defensiveness. The most common move I see that leads people to put up their shields is hearing critical judgments. They’re an almost guaranteed way to trigger people and derail the conversation.

Feedback is effective when it’s actionable. To make it actionable instead of objectionable, feedback masters share observations of people’s actions and their impacts, not judgments. “Response times to client emails averaged 4.2 days last month” lands very differently than “You’re being unprofessional.”

Even if this seems obvious, it becomes challenging when we’re annoyed and feeling justified in our annoyance (“Product just threw this over the wall; they don’t care about our time!”). Our judgments feed our emotions, which then amplify our judgments.

And what seems straightforward in theory can be deceptively difficult in the face of real-world situations. In over 50 feedback workshops across dozens of tech companies, I’ve asked people to share real-world feedback examples, and there hasn’t been a single workshop in which everyone agreed on whether every example we talked through was a judgment or observation.

Fortunately, recognizing and translating our judgments is a skill easily developed with practice, one even more easily practiced now with AI. To do so, you can use this custom GPT or just input this prompt:

Give me examples to practice identifying whether something is an observation or a judgment. Explain why I’m right or wrong after I answer, then give another example, making them increasingly ambiguous each time.

There’s a strong correlation here: the more clearly we see what is impacting progress, the more quickly we can identify new strategies to move toward our Goal.

Laura never called it “micromanagement” to the founder. She didn’t even use the word “feedback”; she just described the actions and their effects as she observed them.

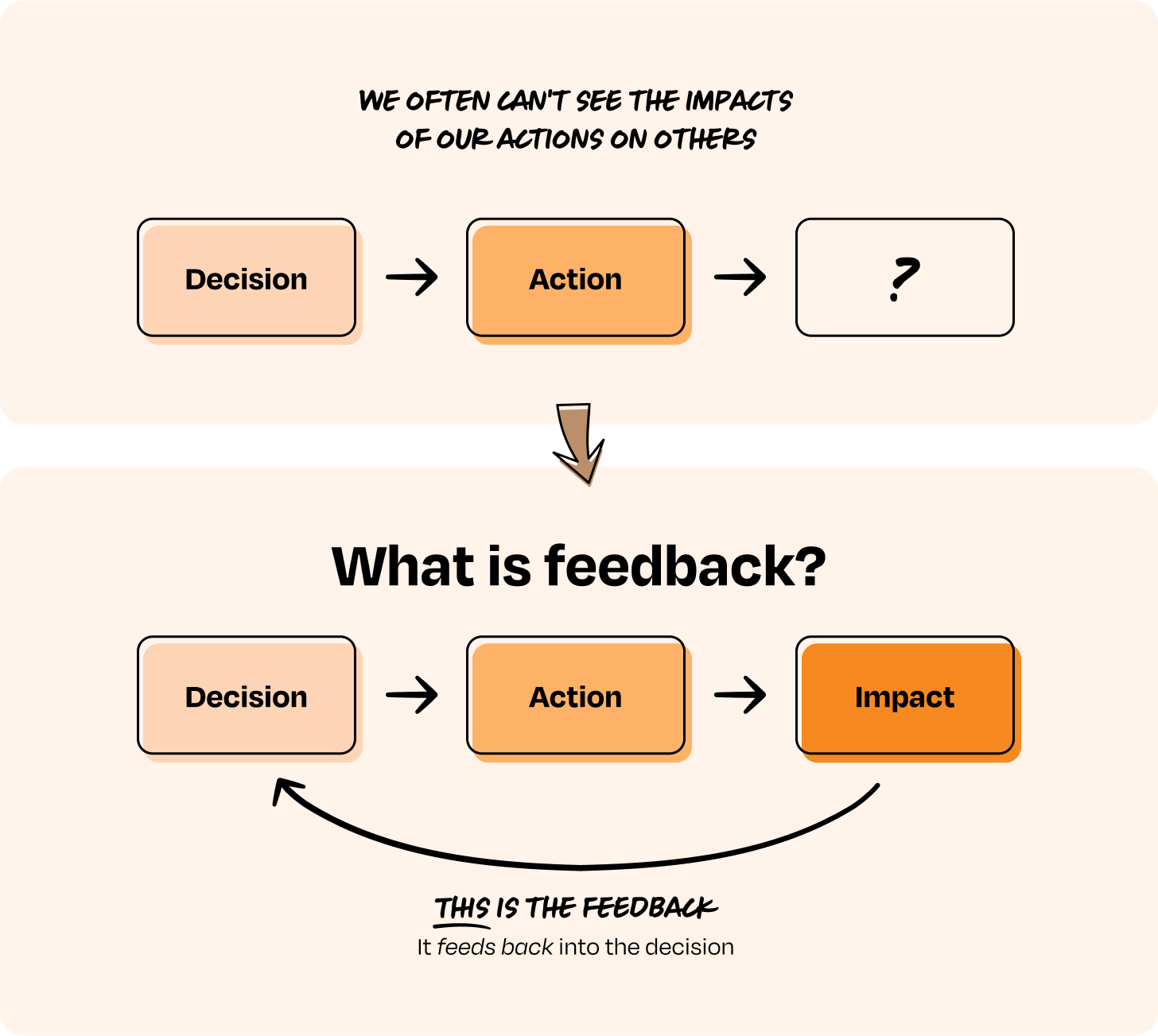

This gets to the essence of feedback as I define it: creating visibility into people’s actions and their impacts. Simple cause and effect is a line of sight that the actor often lacks. Often, not only do we lack visibility into how we are impacting others; we lack the ability to step back from and see our own behavior.

Avoid flattering judgments too

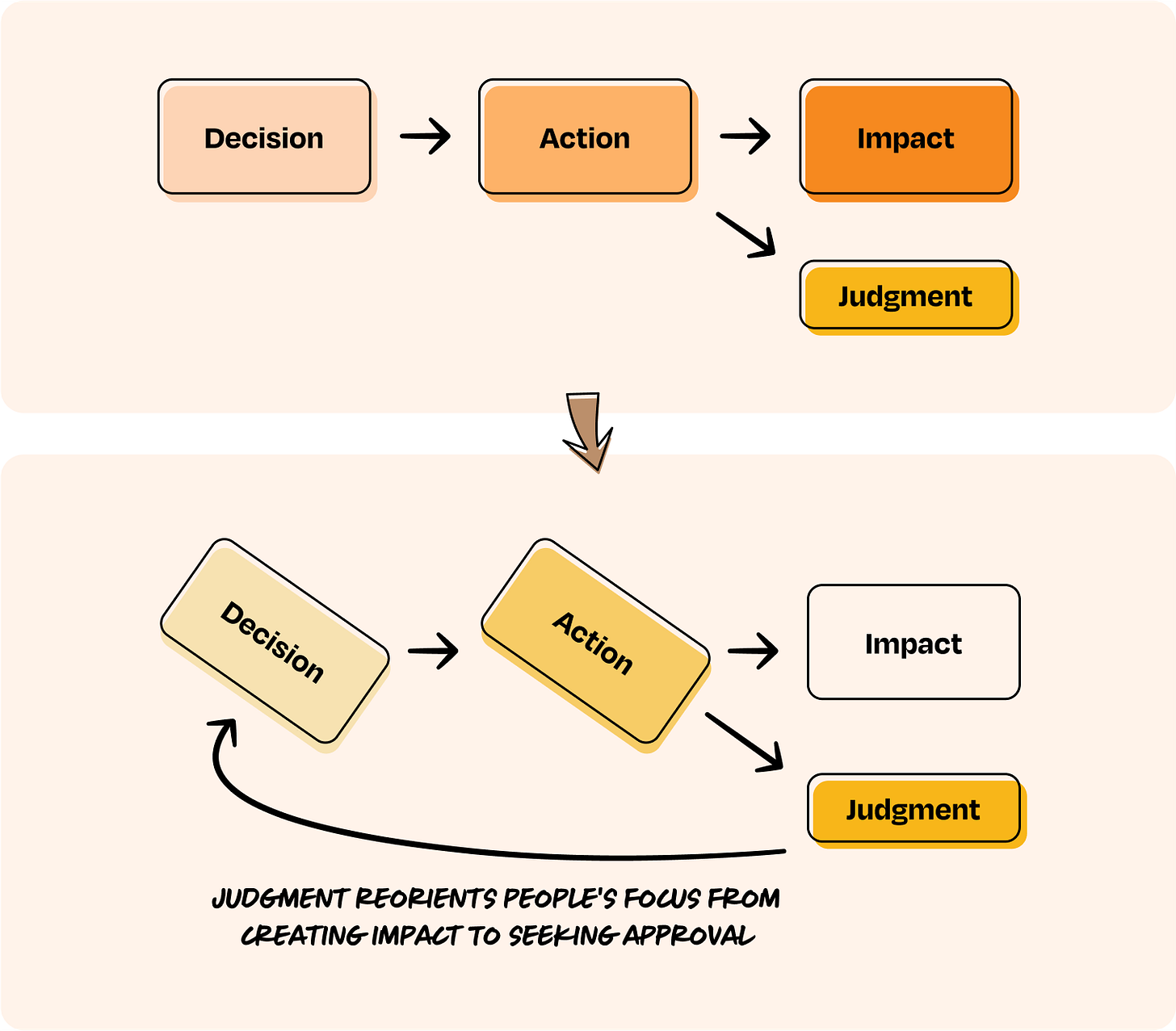

Even for well-practiced feedback masters, it can be tempting to deploy critical judgment’s close cousin, flattering judgment. Well-intentioned people might offer praise and compliments, like “You’re a rockstar PM” or “You’re so brilliant. You have such a gift,” to motivate or thank colleagues. But just as critical judgments can trigger defensiveness, flattering ones can destroy growth mindset, autonomy, and productivity, and foster people-pleasing.

The “rockstar PM” worries about maintaining that image if she fails, turning challenges into threats rather than opportunities to learn and grow. Carol Dweck’s mindset research explains why: If the cause of my success is my brilliance, what does that imply about the cause of my potential failures? This is especially pernicious in contexts that require experimentation, where failure—however temporary—is inevitable. This dynamic is exacerbated when the flattering judgments come from a manager or executive.

That rockstar PM’s focus reorients from iteration and impact to seeking approval.

She could spend a lot of energy trying to get an “Exceeds Expectations” on her next report card—I mean performance review—instead of focusing on influencing user behavior or being more effective in her work relationships.

By contrast, observations of people’s actions and impacts point them to what is within their control—the actions they can change or keep doing and the potential impacts of those actions. They see how to increase their own ability to create their desired outcomes. This means that giving this kind of actionable feedback can actually evoke feedback recipients’ growth mindsets, or as Satya Nadella frames it, help them shift from know-it-alls to learn-it-alls. If you want greater openness and motivation, share impacts, not judgments! Here’s how.

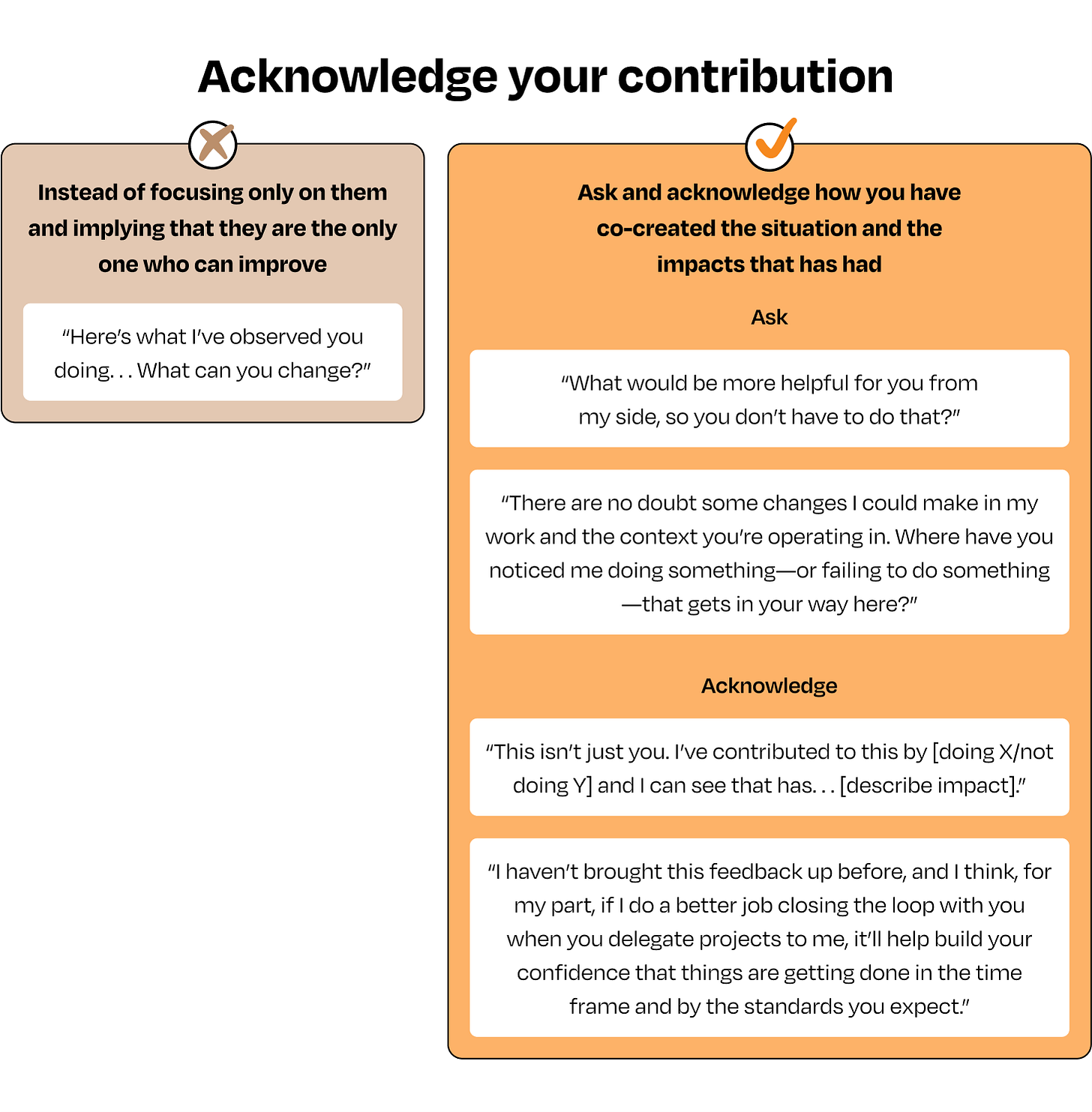

Acknowledge your own actions and their impacts

Judgments aren’t the only trigger for defensiveness. When you as the feedback giver have contributed to a situation but you aren’t noting that, the recipient’s attention can latch onto this gap. “Yeah, but what about your actions?” they wonder. You can preempt this reaction by simply and directly acknowledging your contribution.

As a social species, humans unconsciously mirror the behavior we see in others around us. The crowd waits at a light, and so do we; we start jaywalking, and others are more likely to as well. This plays out interpersonally too. Far too often, we approach feedback conversations with the implicit attitude of “You are the one who needs to change.” From this angle, it’s no surprise that what we get back is the other person looking at us thinking, “No, you are the one who needs to change.” We tend to get what we give.

But this human instinct is actually good news: if you want to lead a conversation and a relationship in a specific direction, just start moving in that direction yourself. The message switches to “I think we can both shift some things that will make it easier to change and move toward that Goal.”

This is one of most disarming feedback approaches I’ve ever encountered—and one of the least-used. Once we have acknowledged our contribution and shown that we are monitoring our own behavior, the other person can release their focus on our actions, freeing up their attention to concentrate on their own actions.

There’s an added benefit here for the feedback giver: shifts that I make in one relationship often apply to other relationships too. When I was frustrated with one client constantly rescheduling, I realized how I was contributing to and even encouraging the problem by always saying yes to requests. Quick check-ins with all my clients around minimizing changes dropped rescheduling requests to zero across the board. More levers, more leverage.

N: Next actions

What do we do with those levers we identified? Once feedback has been shared and received, the final step in an effective feedback conversation is defining next actions. These could be actions for the feedback recipient, the feedback giver, or both.

The clearer and more concrete our action-and-impact observations are, the more obvious the potential next actions become.

Sometimes it’s a very direct link: “Hey, when you don’t schedule interviews in the time frame you said you would, it slows down our hiring process. Can you schedule those this week and let me know if there are any blockers?”

Other times, arriving at next actions is more complex and uncomfortable. Our insides are screaming, “This conversation is awkward. Get me out of here already!” But even an otherwise-great feedback conversation will often amount to nothing if we don’t close it clearly and concretely.

There are a few ways of doing this that increase buy-in and follow-through.

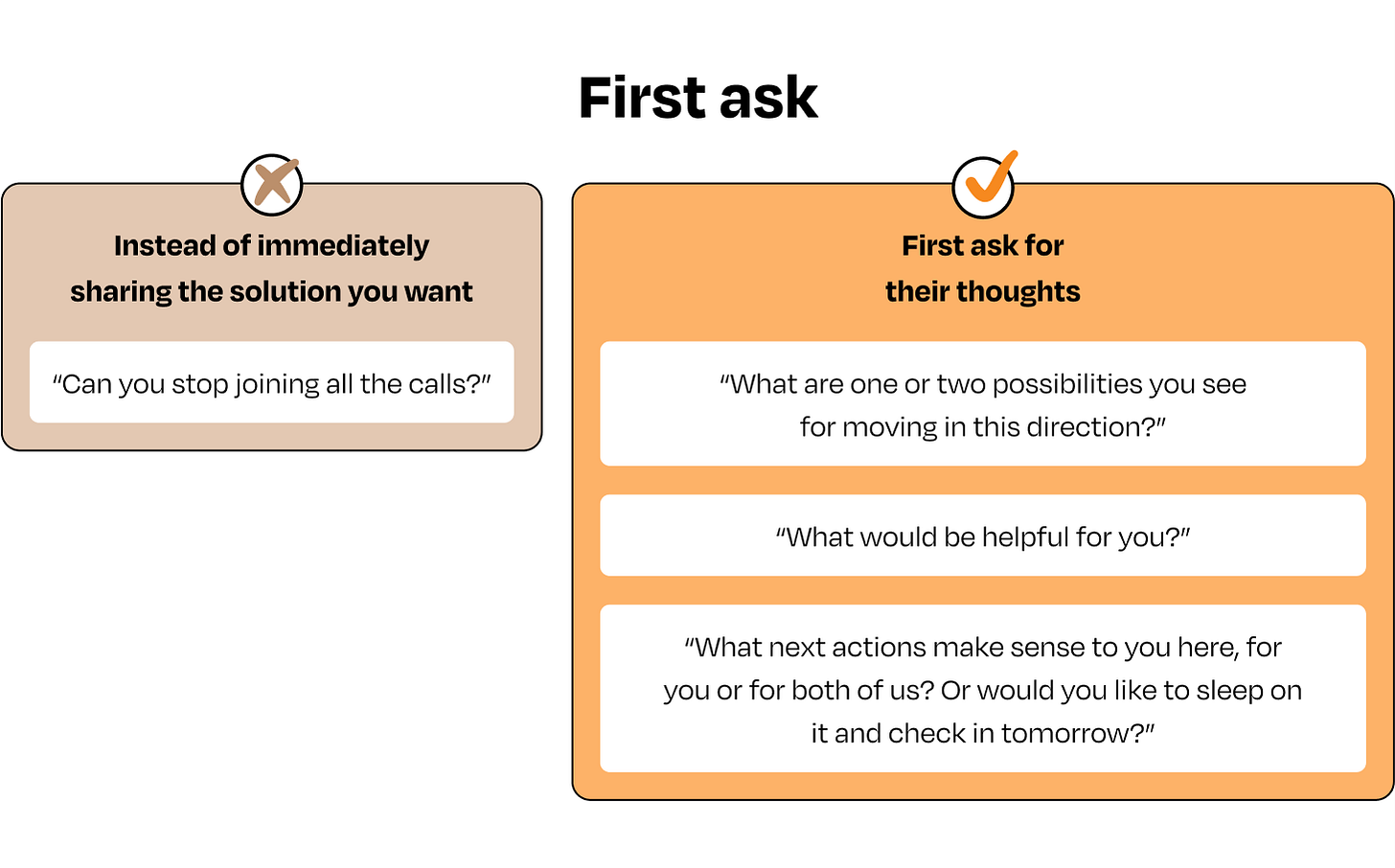

First, ask for their ideas

In an often-maddening phenomenon, people will resist change that they themselves want if it appears to come at the expense of their autonomy. We may want to change, but we want to choose it.

One simple way of supporting someone’s sense of autonomy is to ask for their ideas of what to change before offering our own. When the other person is really on board with the Goal and open to hearing what we’ve shared, given even a few moments of brainstorming, I have found that they regularly come up with useful options I had not considered. They also tend to be more motivated to pursue ideas they have generated themselves.

For feedback that is difficult to hear regardless of how it’s shared, a feedback conversation might actually be a series of conversations, so it’s often best to sleep on it and schedule a future time to return and commit to next actions (not just “later”).

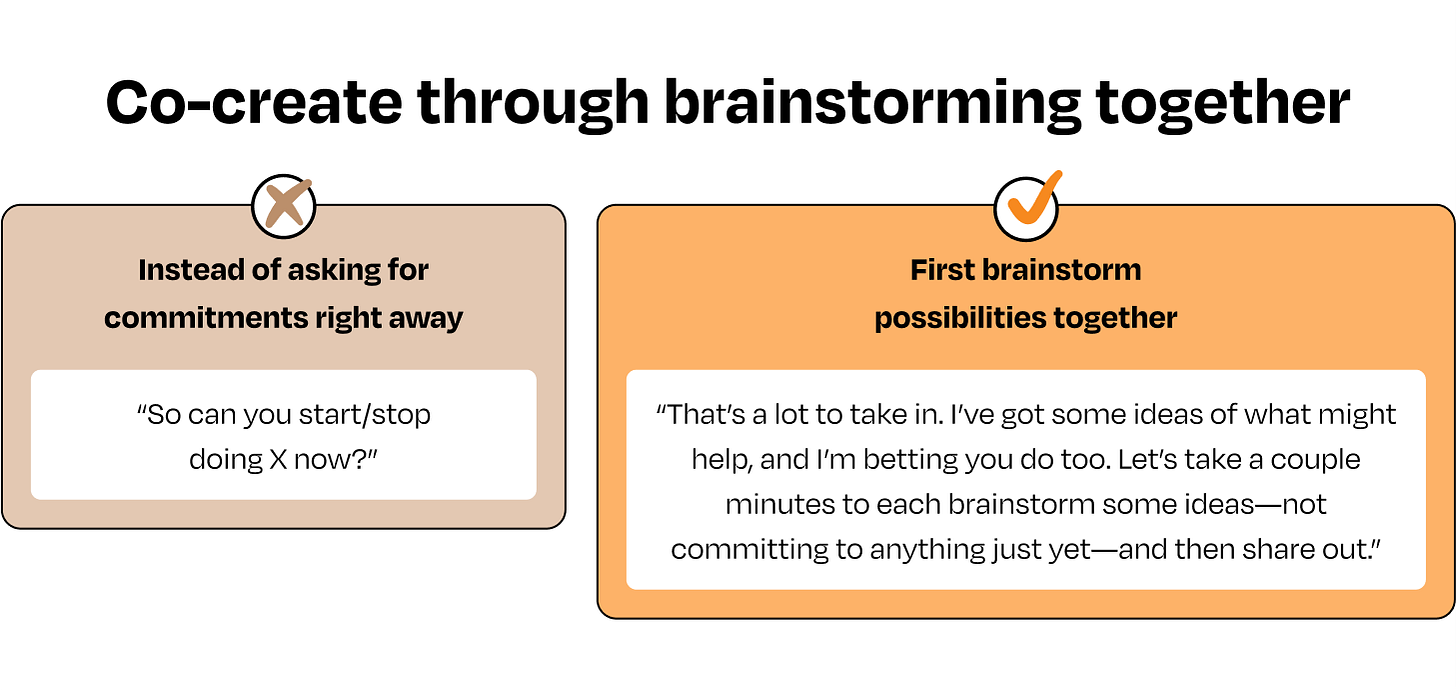

Co-create through brainstorming together

If you are itching to share your own idea but also want to involve them, this option opens up the opportunity for both. It also lets you build on each other’s ideas.

Make specific requests—and make it easy to say no

Sometimes asking for the other person’s ideas can feel disingenuous when all you want is to propose your own. In that case, share your idea, and offer it as a suggestion or a request in a way that still honors their autonomy—in other words, not as a demand.

To support this feeling, make it easy for them to say no to or edit the request. A meta-analysis of 52 studies showed that “Feel free to say no” doubled the percentage of time that people said yes to a request. Supporting autonomy conveys real respect, which preempts resistance, engenders goodwill, and helps people think clearly about the suggestion on its own merits. If they actually say no, you will get to learn what’s blocking them and how to incorporate that in the next actions. (And if you’re feeling attached to your idea and actually want to demand it, remember that it’s the Goal you care about, not the way they get there.)

It’s also important to ensure that your specific request includes what you want more of, not just less of. As psychologist Marshall Rosenberg, the author of Nonviolent Communication, said, “You can’t do a don’t.” Otherwise, when they find themselves in the same situation again, they’ll be unclear about what alternative behavior to engage in.

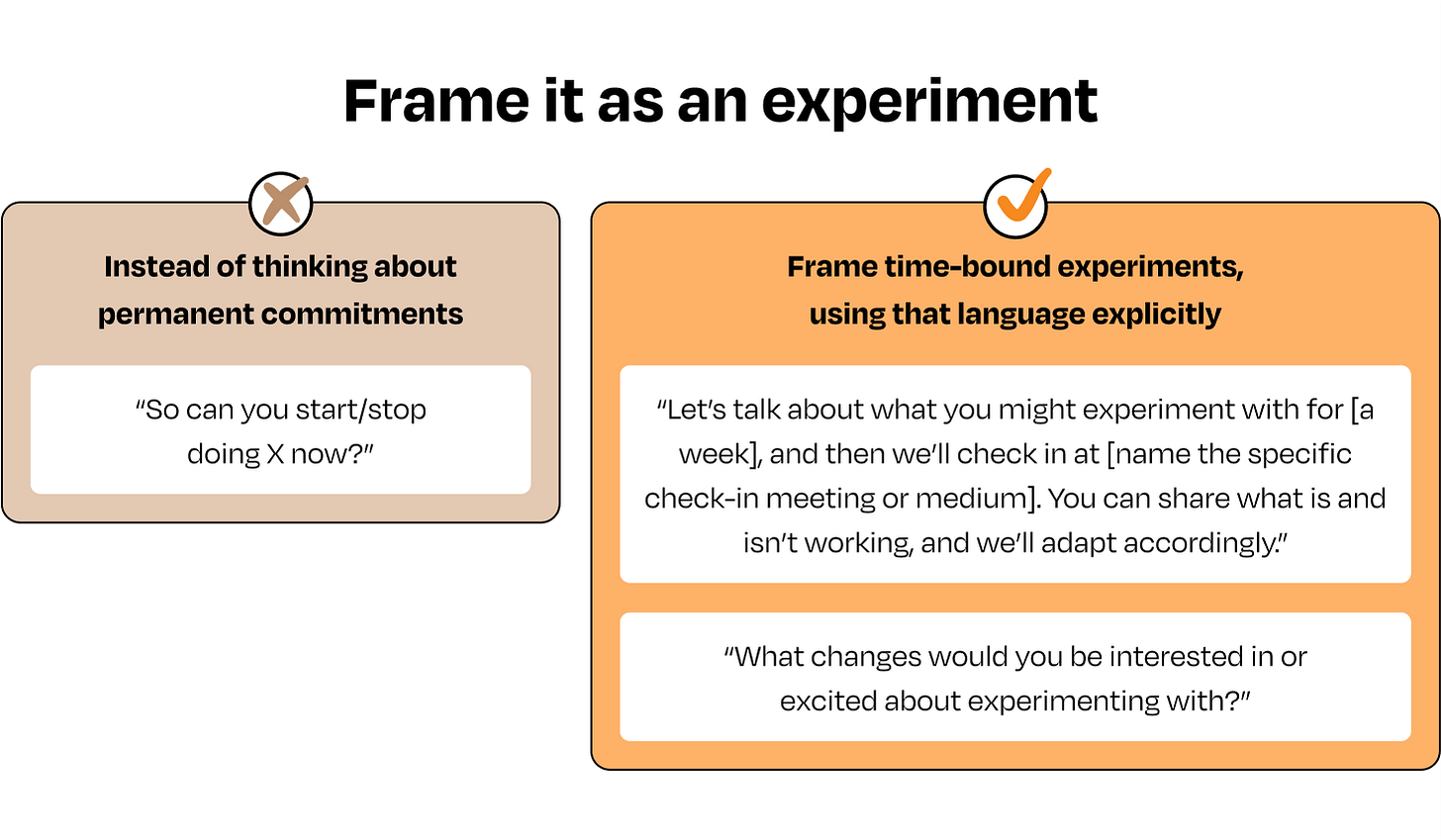

Frame it as an experiment

When someone is considering a new behavior, that means there’s an element of uncertainty. Understandably, there can be some hesitance about committing to do something they’ve never done before, no matter how much they follow the logic. Instead of committing to something new “forever,” explicitly acknowledge it as an experiment for a set time period.

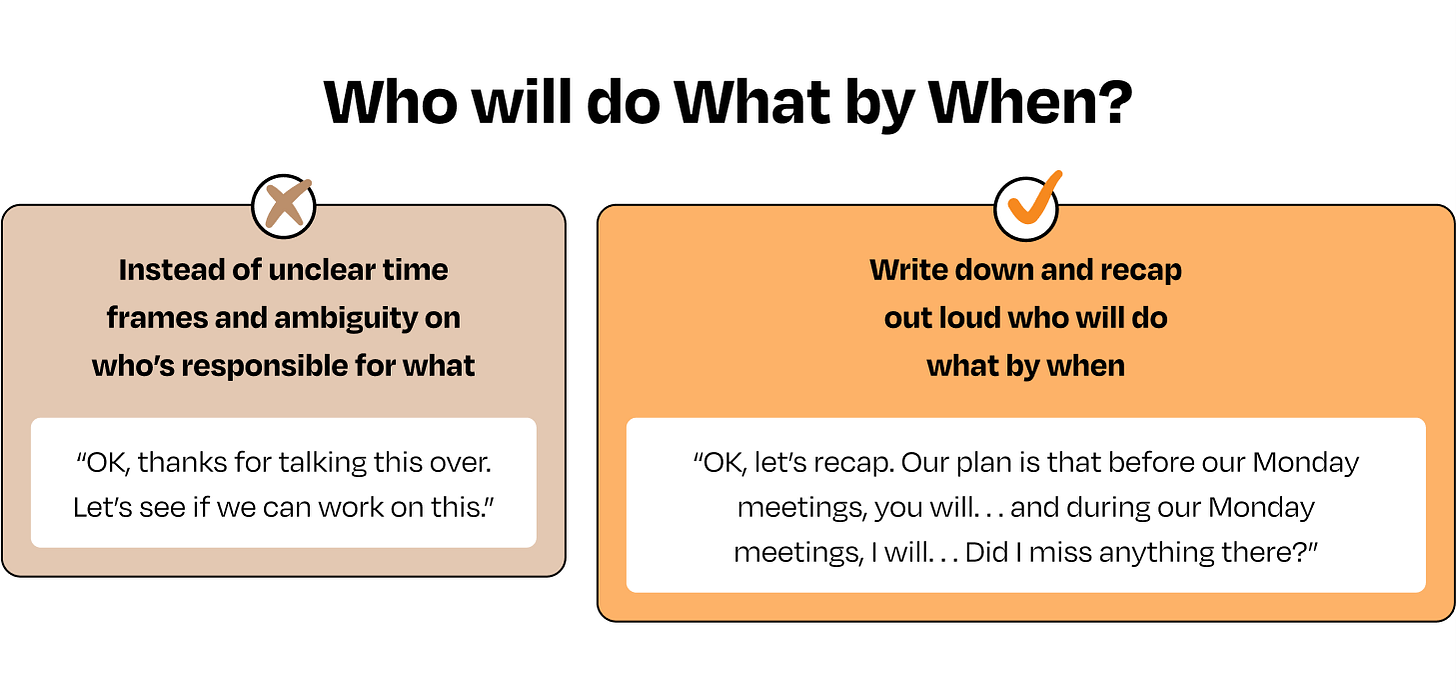

WWW: Who will do What by When?

This question moves growth, progress, and whole companies forward faster than any other one I know.

“Let’s” and “should” are insidious impostors when it comes to action items. Let’s: Is that you or me? Should: Is that an idea we’re considering or a commitment? When you hear these words, use them as an automatic signal to pause and clarify who will do what by when.

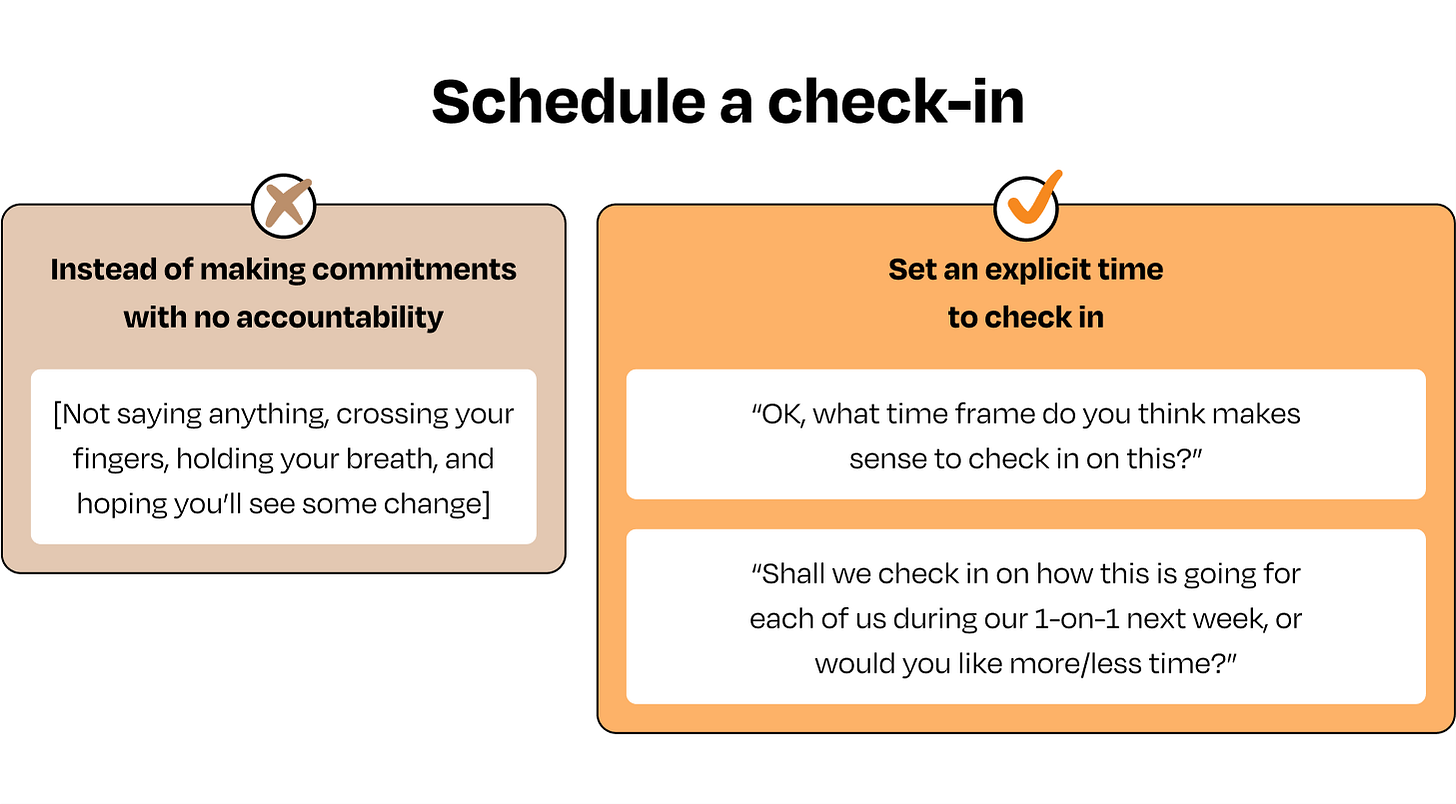

Schedule a check-in

If you don’t set a clear check-in, you run the risk of not seeing the change you were hoping for and having to initiate a follow-up feedback conversation if you still want to close the gap. The discomfort of this is higher, so it’s easier to avoid, and the frustration festers into resentment and helplessness. If instead you establish a time and date to check in, you set up three more desirable possibilities:

An agreed-upon check-in time often increases the accountability and expectation of change.

The behavior may have changed, and you have a built-in moment to appreciate the impacts you’re seeing and the progress toward the Goal, encouraging even more development. This reinforces a growth mindset.

If the behavior hasn’t changed or hasn’t had the desired impact, you will recognize this sooner and be able to troubleshoot and course-correct faster.

AI in feedback

That’s a lot to digest and consider when preparing and leading a feedback conversation. Fortunately, you’re not on your own anymore.

While many people fear AI will erode human connection, I see the opposite happening with clients and in our workshops: People are using AI as a tool for expanding interpersonal skills and deepening human relationships.

Here are three ways AI can support you in using the GAIN approach and having much more effective, connective feedback conversations: