Lessons learned from a startup that didn’t make it

What not to do when building a B2B startup

👋 Hey, Lenny here! Welcome to this month’s ✨ free edition ✨ of Lenny’s Newsletter. Each week I tackle reader questions about building product, driving growth, and accelerating your career. If you’re not a subscriber, here’s what you’ve missed:

Subscribe to get access to these posts, and every post.

Failure has a lot to teach us. But we usually miss our chance to learn from it.

Recently, in the process of shutting down his startup, Jake Fuentes (co-founder and CEO of Cascade) jotted down his biggest lessons from the journey. I found them incredibly insightful, and applicable to most startups and product teams, so I asked him if I could share them broadly. Below, Jake offers his hard-won lessons about what people forget about competition, how early market signal is often deceiving, what it takes to build horizontal products, the danger of unfocused ICPs, and more. These lessons are especially timely with the conclusion of my recent B2B series.

For more from Jake, follow him on LinkedIn and X. He also advises companies considering acquisitions or other strategic options. Learn more and get in touch on his website.

“So, what did you learn?”

It’s meant to be a simple question, asked by friends and family in the months after the end of a startup journey. But when looking back on a company that didn’t go the distance, so many lessons emerge that it’s daunting to find an equally simple answer. That said, I’m struck by a few key decisions we made that seemed sound at the time but that ended up having a profound impact on the company’s direction. I doubt we’re the only team to face those junctures—perhaps our hindsight can serve as a tiny bit of foresight for others.

We started Cascade in 2019 destined for glory. Both founders were repeat entrepreneurs with prior exits, we were backed by top investors including First Round Capital and Redpoint, and we had a spectacular starting team. We sat at the intersection of the no-code wave and the red-hot data space: our product gave non-technical teams a way to import, analyze, and visualize large data sets and present their findings via an interactive data app. In our previous companies, we had been surrounded by ambitious but nontechnical business analysts, and we saw how much time they spent fighting Excel and updating charts in PowerPoint. Over the next four years, Cascade raised a $5.3 million seed round, grew to be a team of 10, and served some marquee customers. However, without a clear path to breakout growth, in 2023 we decided to pursue a soft landing.

Here’s what we learned.

If you allow your ICP to fray, you’ll lose

From the beginning, we knew we needed to define a good ideal customer profile (ICP). There are many approaches to defining a good ICP, but a quality we underestimated is specificity. Simply put, an ICP must be a single market segment: a group of people for whom the value of solving a problem is roughly the same, and who can be reached in roughly the same way. “People who use Excel” is not a market segment, because it says nothing about either the value of their problem or how to reach them. “Marketers who use Excel to build content calendars at Fortune 500 companies” could be a good market segment, depending on how you reach them.

We defined our ICP as nontechnical business analysts using Excel to crunch big data sets. In retrospect, that was much too broad, particularly because it said nothing about why they were using Excel or the value of the problem they were solving with it. So we ended up with a large basket of ICPs: a scooter company used us to manage location data, an HR team used us to manage employee data, and a retailer used us to analyze distribution. We didn’t really have a framework for accepting one and rejecting another, so we tried to support them all.

If we had a properly defined ICP, we would have seen it start to fray with each new use case. ICP fray confuses every decision for a very simple reason: to know what problem you’re solving, you need to know who you’re solving it for. On the journey to product-market fit, we know products often change quickly. But the chances of finding fit go down dramatically if the market is changing as well. Therefore, every other decision is downstream of a clear definition of who your audience is. Encountering demand outside of your ICP may seem like a good thing, but be very careful about supporting those customers and expanding to a new segment. Yes, you may discover a whole new market for your product, but along the way, recognize that you’re allowing your customer focus to fray. Either validate the new market segment and pivot into it, or stick to your guns and move on.

Horizontal products are only as good as their best vertical use case

We justified our broad approach and basket of use cases because we thought about ourselves as a horizontal product (a toolkit built for multiple use cases rather than a single solution). We looked at Airtable, Notion, and Webflow as successful examples of horizontal plays, and we salivated when thinking about the aggregate TAM of all the use cases we could support.

We needed to remember that our customers do not care about our TAM. All they care about is their specific set of problems. Building a horizontal tool is especially hard, because each supported use case often competes with a tailor-made, vertical solution. If we had tried to build a whole business around the scooter company that was using Cascade to manage logistics, we would have quickly run up against Samsara and Onfleet.

Horizontal products win if a specific audience encounters enough use cases that they want one tool to address them all. Figma won because it captured a much larger portion of an app designer’s workflow than Sketch or Illustrator did. Notion won because it addressed the vast array of documentation tasks faced by product managers in San Francisco. In both cases, a specific buyer encountered a large array of problems, so a horizontal toolkit was the best solution.

As we took Cascade to market, we were dismayed to find that the business analyst role had changed, making us less relevant. A lot of big-data wrangling and analysis was being shifted to more technical data teams, for whom Cascade had little value. Business analysts at midsize companies no longer faced the diversity of analytical problems they used to, which meant that more opinionated, targeted products could pick up what was left. The diversity problem still existed upmarket, but that meant we would have to build a large number of enterprise features in addition to what we had.

We knew that horizontal tools often must survive a very long, uncertain journey toward product-market fit in order to support all the use cases they need to. During that time, we knew our customers would reject the product for ambiguous reasons, our team would second-guess our strategy, and our investors would tell us to pivot. We stuck to our guns for over three years, convinced that we could build our way out of it. But the further we got, the more it felt like we had landed on a melting island.

A competitive product being old and clunky doesn’t mean it’s vulnerable

We thought we had landed on a startup gold mine. Alteryx, an early-2000s-era software company, was about to clear a billion dollars in annual revenue. Their only product was a Windows-only, clunky desktop application for which each user paid over $5,000 a year. They were the only player in their esoteric market and seemed incapable of delivering anything that resembled modern software. Getting the application started took several incantations and a minor miracle, and one look at the interface revealed a stark contrast with the lightweight, browser-native applications we were used to. We set out to build a competitor, confident that we could out-execute them and steal major market share.

The problem was that Alteryx users actually liked the product. It was clunky and probably needed to be moved to the cloud, but it delivered on its promise, giving its nontechnical users the ability to build logic the way their engineering teams did. Over the past 15 years, it had also amassed a community that helped each other solve complex data problems. The desktop app was a big part of the offering, but the community had helped solidify its moat.

We chalked all that up to the fact that users had no real alternative. Besides, we knew that Alteryx was horrendously expensive, which left buyers frustrated even if end users were not. While most of their customers were not actively seeking an alternative, cost alone led to reasonable success getting companies to evaluate their options. If we could overcome switching costs, we saw a path to real growth.

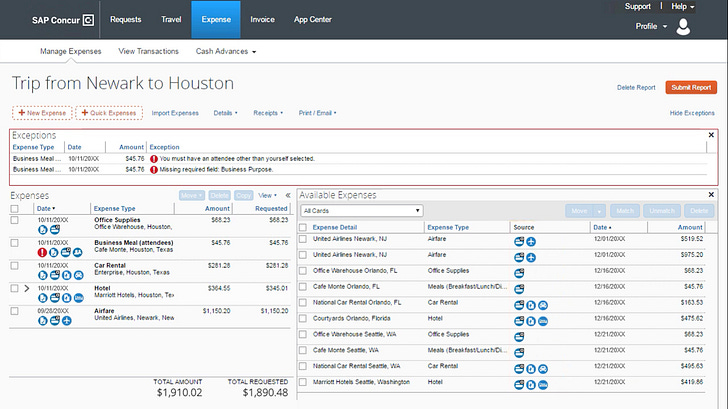

Generally, teams think about switching costs as the amount of time and money needed to install one solution and remove another. But true switching costs are much more than that: they include the politics, emotions, career ambitions, esoteric business processes, competing priorities, and sheer laziness that all favor the existing solution. Those forces can be incredibly strong, working to ensure that inferior products can still win (have you ever used Bill.com, Concur, or even Salesforce?).

In our case, we underestimated how deeply Alteryx was integrated into company processes. Only a couple of people inside those companies actually knew how Alteryx worked, and hell would freeze over before we convinced them to abandon a career-defining tool. While “normal” users were willing to switch, we didn’t go far enough to facilitate replacing old work and to convince power users that we were the future. We thought the product would speak for itself. While it did to some degree, we needed more.

Many old-school companies seem ripe for disruption but are actually much stronger than they appear. Others appear strong but are secretly vulnerable. If only the user is frustrated, you’ll have a hard time winning. If only the buyer is frustrated, you have a path to victory as long as you can overcome switching costs. Only direct input from customers will reveal the true story.

Don’t confuse people rooting for you with market signal

On some level, all founders suffer from “happy ears”—the chronic confirmation bias pervading conversations with customers, partners, team members, and investors. We tend to have irrational levels of confidence anyway, but that gets compounded when we mistake support for market signal. Most commonly, founders believe that investor checks signal that they’re on the right track. That could be true, but at the seed stage, investors often make a broad bet on the team, trusting that they’ll figure something out. If founders read more into an investment than that, they might double down on a bad strategy because of some perceived investor confidence.

The phenomenon goes further than investors. Before a product can speak for itself, a company’s earliest deals are often done on the backs of the founders’ personal relationships. While those early deals are often critical to the company’s survival, they’re also not true market signal. Your supporters will be rooting for you and want you to succeed, and at times they’ll be in a position to accelerate your progress. Unbeknown to them, sometimes they can accelerate you in the wrong direction.

That’s especially true if you have a product like Cascade, which has multiple use cases and a broad value proposition. Our customers hired us because they liked or trusted us and because the founders were involved in the deal. But once the founders stepped out of the room, things got a lot more difficult. The founding team could push the car forward, but we mistook that movement for a machine that could run on its own. Once we stopped pushing, the car stopped.

Looking back, I’m struck by the insane number of forces pulling companies away from product-market fit. Founders need to plow through a murky market, propelling their journey with the right team, stepping over competitive land mines, turning based on the right feedback but not the wrong feedback, and suppressing their own biases in order to see their environment clearly. Along the way, we often look to learn from companies that have gone the distance, succeeding in spite of the odds. But success stories (and the revisionist narratives told about them) often don’t do enough to highlight the common misconceptions, obstacles, or mirages that face new companies. I hope our story, with all of its ups and downs, will add a few more signposts along the road.

Have a fulfilling and productive week 🙏

📣 Join Lenny’s Talent Collective 📣

If you’re hiring, I can help. Lenny’s Talent Collective works with a select group of companies every month to help them make key growth and product hires.

You tell us what you’re looking for, we scan through our entire community to find the best fits, and introduce you directly to the candidates you most want to talk to. I hand-review every potential intro to ensure a great experience for all parties.

If you’re looking for a new gig, join here! We’ll send over personalized opportunities from hand-selected companies if we think there’s a fit. Nobody gets your info until you allow them to, and you can leave anytime.

If you’re finding this newsletter valuable, share it with a friend, and consider subscribing if you haven’t already. There are group discounts, gift options, and referral bonuses available.

Sincerely,

Lenny 👋

Too many good quotes in one post! "Horizontal products are only as good as their best vertical use case" is a standout. Thanks for sharing the lessons learned, Jake 🙏

I worked 9 years in corporate and I founded and run a data company called dyvenia, we do well, but we are still mostly consulting revenue even though I am shifting some revenue to services and licenses. I basically started my data journey with Alteryx and Tableau. On Alteryx you forgot to say they grew a lot by siding with Tableau, they had their ICP well defined in that case: Tableau users that needed to do quick data modelling for their dashboards. Tableau Prep came a lot later and now PowerBI has its own modelling tool, so in fact I think Alteryx is in trouble now, less so 3 years ago. I likes your analysis, especially your insight on horizontal tools, I am in fact trying to go vertical myself now after trying to sell an horizontal tool for about 1 year. I would recommend to include in the team someone who has done enterprise work or sales next time, UI is never the problem with Enterprose tools, you need to fit in the internal narrative of the Enterprise buying committee, and they will always go for whatever they thing is “standard” or “best practice” at the moment.