👋 Hello, I’m Lenny and welcome to a ✨ once-a-month-free-edition ✨ of my newsletter. Each week I humbly tackle reader questions about product, growth, working with humans, and anything else that’s stressing them out at the office.

If you’re not a paid subscriber, here’s what you missed this month:

Q: I have a self-serve bottom-up SaaS product, and I'm trying to decide if, when, and how I should hire my first full-time salesperson.

One of the most surprising takeaways from my research into early B2B growth was that 100% of the bottom-up B2B companies ended up layering on a sales team. It’s rarely a question of if — it’s a question of when, and how.

Since I don’t have a lot of depth in sales myself, I went straight to my go-to person for all things sales: Pete Kazanjy. If you don’t know of Pete, he wrote THE book on startup sales, which he recently released as a physical book. This tweet was not an exaggeration:

Pete generously agreed to write a guest post, and unsurprisingly, below you’ll find the most in-depth and tactical guide for adding sales into your org. Including:

Should I start with a self-serve product?

Should I ever involve salespeople?

When should I add a salesperson to the mix?

How do I set myself up for success during The Transition?

Common pitfalls to avoid

Let’s dive in!

A bit more about Pete: In addition to authoring Founding Sales, Pete Kazanjy is also the founder of Atrium, makers of data-driven management software for sales teams, and founder of Modern Sales (the world’s largest peer-education community for sales operations and leadership professionals). He previously started and sold TalentBin (a recruiting software startup) to Monster Worldwide. You can find him on Twitter and LinkedIn.

The Transition: Layering Sales onto a Bottom-Up Self-Serve Product

By Pete Kazanjy

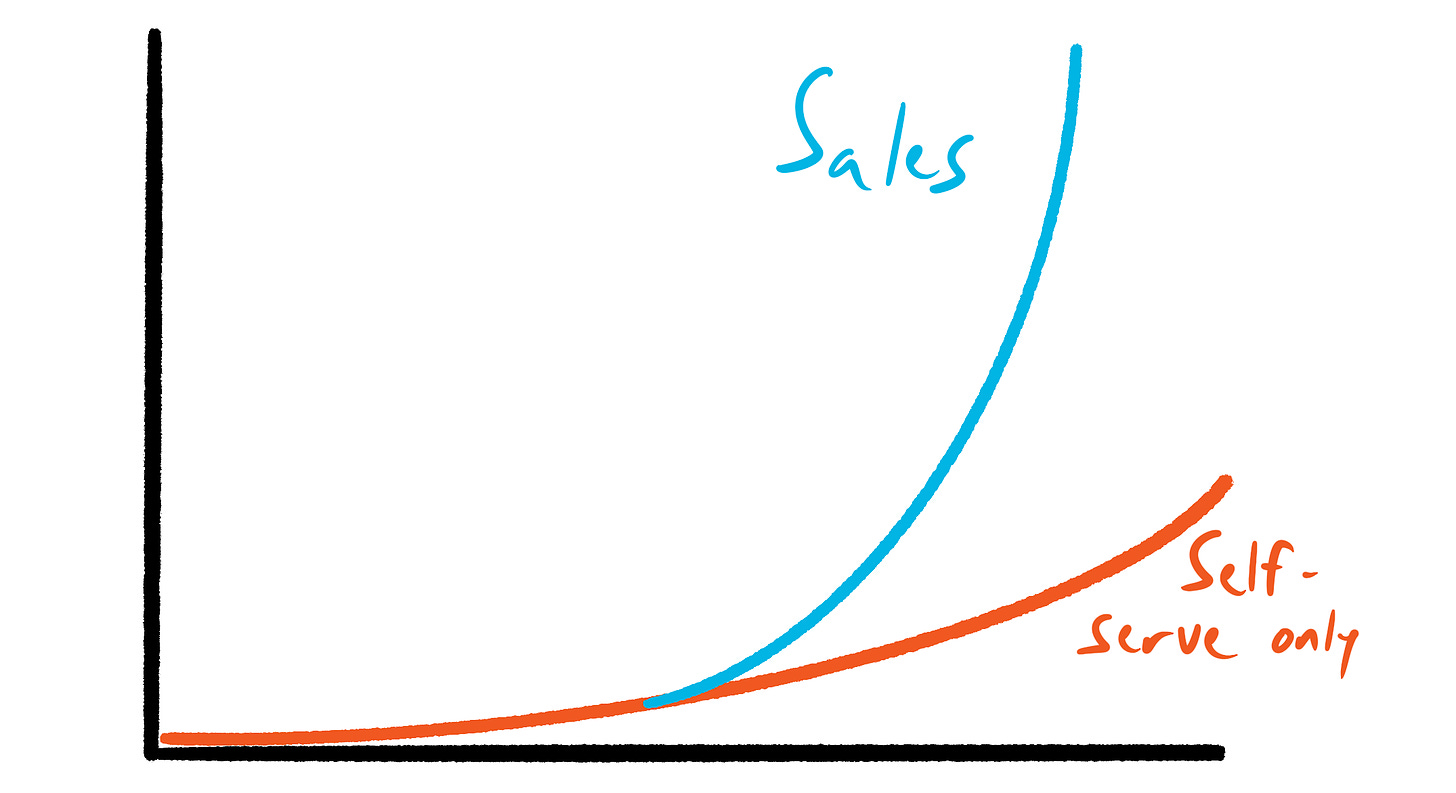

“Bottom-up” (or “product-led”) B2B growth is a hot topic in early-stage circles these days, and it makes sense why. A self-serve (“easy-in”) entry motion, that’s later combined with a strong direct sales motion, can make for explosive revenue growth as shown by IPO’d exemplars Zoom, Slack, Datadog, and private market dynamos like Airtable, Figma, and others. The combination of bottom-up self-serve plus direct sales can simultaneously lower CACs and power larger contract values (with expansion into enterprise contracts). This would never be possible in a pure self-serve model.

The crux of this article is that waiting too long to add sales-involvement often leads to a large opportunity cost. Many successful self-serve applications saw their market position usurped by competitors who adopted a sales-assisted motion and effectively firewalled the self-serve-only products out of lucrative enterprise segments (e.g. Dropbox).

Below, I’ll help you understand if layering in sales is right for your business, when to take the leap, and how to navigate this critical transition successfully:

First of all, should I even start with a self-serve product?

Self-serve has a lot going for it, but it’s not necessarily a slam dunk decision for every product. Below are four questions to take into consideration before building a self-serve product (many of which can be answered before you launch):

1. Is the product simple enough for self-serve?

Successful self-service is about allowing a user to get to success and have that “aha” activation moment on their own. So the question that follows from this is how easy is it for users to get to that aha moment? Zoom is not complicated. Send someone a link or join someone’s link, and boom, you’re talking to them. Dropbox is pretty straight forward – download this client, and tell it what folders to sync. Airtable is a bit more advanced, but you can start simple, and they’ve invested heavily in a content catalog of templates and recipes to allow for self-served advancement.

Note, “complexity” is audience contingent. Tableau is not an easy product to use by any stretch of the imagination, but it’s self-serviceable by the technical data analysts for whom it was designed, and as such started self-serve with a desktop client download. Similarly, Stripe, Datadog, Twilio, New Relic, and other developer tools have all started self-serve, in that their technical audience has the capacity to self-serve even these more involved products. Some offerings are really just too complex to start self-serve, such as enterprise-grade marketing automation platforms like Marketo, and software targeting massive financial enterprises like Blend.

2. Is this truly new and differentiated?

If your offering is truly new and differentiated, self-serve can be fantastic. When Yesware and Mixmax first launched, most organizations didn’t have any sort of sales engagement email offerings for their salespeople. The notion of sending someone a link to a public calendar with which to book time was crazy talk when Calendly first launched. Software that proactively monitors your revenue stack’s automations and linkages for errors has never existed, which is why Sonar can be self-serviced by sales and marketing operations staff. Personal business cloud app search has never existed before, and thus there’s no reason for a given user in an organization to not download and give Command E a try.

3. Can this co-exist with a (less good) incumbent in a given company’s stack?

Conversely, if your offering can coexist alongside inferior incumbents, self-serve can also work. Most organizations where Slack was adopted early-on already had Gmail and thus GChat. Organizations that start using Guru may have antiquated knowledge bases in Sharepoint or in Confluence wikis. This is where my company, Atrium lives. Customers will frequently have legacy analytics infrastructure, like Tableau or Looker, in place, but its complexity underserves the needs of the sales organization, leaving open an opportunity for Atrium to enable data-driven management for sales managers and sales operations staff in a way they’re currently not doing. Tableau and Looker still end up existing in the organization, but for more advanced analytics run by a data or analytics team.

By contrast, an “end to end” offering like a Human Resource Information System (e.g. Workday) or email sending platforms (e.g. Iterable) are not something you have “two of” in an organization. As such, even though Sapling makes delightful modern HRIS software, they don’t have a self-serve offering. Iterable makes great, modern customer engagement software, but it’s highly unlikely an organization would run a legacy system like Responsys and Iterable side by side. Self-serve would likely not work for them.

4. Will you focus on small organizations?

If none of the above apply, you can still target smaller orgs that have not yet adopted a legacy provider with a self-service offering. Stripe is a great example here. Payments providers already existed when Stripe first came on the scene, so it was less likely for a mature e-commerce provider with an existing payments provider to switch to a new upstart. But because legacy providers were clunky with poorly documented APIs, Stripe was the obvious choice for new internet businesses who didn’t yet have a payments provider.

RevOps makes fantastic quoting software for sales organizations that can be self-setup, but there’s no way anyone who already has Salesforce CPQ or Apttus is going to switch over to them. But for a 10 person sales organization that wants to systemize the creation of quotes and sending proposals, the idea of solving that problem in less than 5 minutes (rather than 3 months, like a standard Salesforce CPQ deployment) is really attractive. Which is why self-serve works for RevOps, specifically targeting this down-market segment.

Should I ever involve salespeople?

Once you’ve determined whether self-serve is right for you, growth is going well, and you’re on your merry way (i.e. people are self-serving, getting to “aha”, transacting, and retaining), the next question would be “OK, well, should we get some salespeople involved here?” Well, that depends.

There are two primary reasons to add salespeople to a self-serve commercial motion:

To facilitate the penetration or expansion of your solution into an organization where it has an initial foothold, and/or

To help raise conversion rates of your self-serve offer

It turns out, humans are really helpful when it comes to smoothing over weird edge cases, communicating complicated concepts, and persuading other people to surmount their inertia and try a new thing. They’re good at, you know, selling! But there’s a downside. Humans are expensive, and can only do so many tasks in a given amount of time - as compared to software which, once written, is really cheap to run, and can be scaled up to do as many tasks as you like.

So the question of “should I add sales to the mix?” is one of “will it help?” and “will the juice be worth the squeeze?”

1. Facilitating the penetration or expansion into an organization

This is the approach Slack and Zoom’s early sales motions helped with. It wasn’t about a salesperson showing up to an organization and saying “Hi, you need intra-organizational communication assistance, you should check out Slack.” Rather, teams within organizations might start using Slack to communicate amongst themselves, and the addition of an “Account Manager” (psssst...it’s a salesperson) helped unify those various pods into a single contract, while potentially adding more pods, was powerful. Similarly, in a more “single-player” offering, like Command E, a handful of sales people in a 200 person sales organization might start using it to search their Salesforce opportunities, their Google Docs, and their Gmail, but a “Customer Success Specialist” (psssst...it’s a salesperson) offering to “give a personalized tour to the rest of the sales organization” could also be quite powerful (for expansion).

2. Helping with conversion

Sometimes even supposedly simplistic offerings can have sharp edges or places where a user can get hung up on their way to an “aha” moment. This is another place where “sales” people can be helpful. I use the quotes because this frequently looks more like support and customer success than it looks like sales, but the goal is the same: get the user to success so they can transact. Much of this will be addressed by product or marketing approaches via programmatic email, in-product guides, and so on, but in cases where you might know it’s worth it to engage the user to assist with their conversion, having dedicated people to do so can be helpful.

How do you know it’s worth it? Imagine a situation where the average user of your software ends up spending $5,000 a year. And further imagine you know that engaging with a hung, unactivated user doubles the probability they convert to a customer from 10% to 20%. Lastly, you know that the time cost of doing so is a couple of hours, by a staff resource that costs $50 an hour. With those inputs, we’re essentially saying “I can spend $100 in human labor to capture $500 in expected conversion upside.” In this case, it seems it might make sense to have a “sales assist” salesperson.

That said, Snowflake’s probably not going to be sales-assisting every abandoned user who signs up for an account and bails. If you can differentiate between the valuable hung users and everyone else, this can work. For example, if early Slack sees that a Director of IT from, say, Tesla had signed up for a Slack account, and abandoned their instance before inviting anyone else or setting up channels...well, I have a hunch that it might be worth a person’s time to engage with that user, by phone, by email, maybe even by candygram to see if we can get them to success. This is what is often known as a “qualified” or “gold” lead that, in this case, has been generated by your product.

This realm is where my company, Atrium, sits. Because it takes less than 90 seconds to sign up and stand up a sales performance analytics harness, we get a lot of people “checking it out.” Because our average sales price is high enough (in the many thousands of dollars), it’s very much worth our while for a salesperson to engage with abandoned users who fit the criteria of a potentially successful customer - which, amongst other reasons, is why we have a sales team full of delightful, helpful humans to do just that. For more on how to differentiate between an ideal customer who’s “worth the time” and those that aren’t, check out this section of Founding Sales on the topic.

The other thing to consider is something I call “commercial conversion”. You might not have issues with users getting to product value, but there could be other barriers to successful conversion. Security audits, sign-off from the procurement team, you name it. This is another reason why having humans involved can be helpful – a head of data infrastructure that wants to take Snowflake off her credit card, and get procurement to start paying via invoicing may need some hand-holding. Providing that can be in your best interest, along with an easy means by which to “Contact Sales” on your home page and in your product to facilitate that.

All that said, you have to make sure the economics pencil out. Humans are not cheap, so you need to make sure that the added human labor costs are worth the enhanced revenue upside. Generally speaking, you want to see a salesperson delivering 4x their fully loaded cost in incremental revenue. So make sure to do the math on how many of these unique potential transactions (“opportunities” in sales speak) a given sales rep can handle in a given time period and what the value output might be.

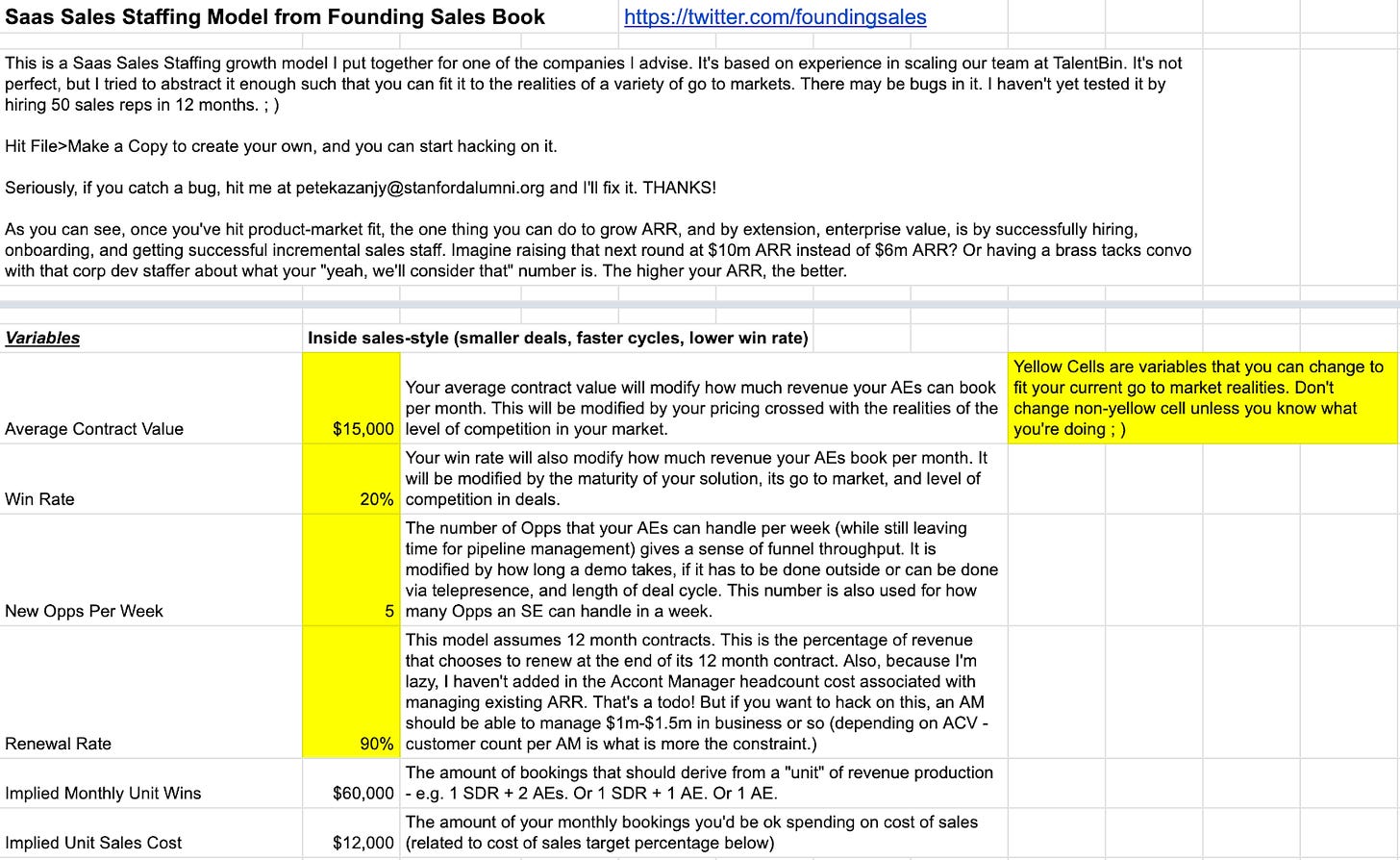

For example, let’s say it takes on average two 30-minute meetings per opportunity (both wins and losses), a rep can have 20 of these meetings a week, thus 80 per month, giving you a 40 opportunity “budget” per rep per month. Let’s say this capacity costs us, say, $10k in salary expense and commission for a junior AE - meaning a cost of $250 per opportunity managed. If we get $5k out of each successfully won opportunity, and win 25% of those engaged - well, that’s 10 wins out of 40 monthly attempts, for $50k of revenue, on a sales rep cost of $10k. Not bad! We should test this out! You can use this rudimentary SaaS Sales Staffing Model to play around with what this could look like for your offering.

You have to at least have a credible hypothesis that this could commercially work for your offering before engaging wholeheartedly in the effort (or, testing it, meaningfully.). By contrast, if you do the above math and it feels more like you’d be getting $20k of bookings out of a $10k of rep costs...sales assistance may not be in the cards for you. Unless you can raise your prices, lower the costs of your reps, raise your win rates, or substantially increase the number of opportunities a given rep can handle in a time period.

Some organizations push the envelope here by locating lower-end salespeople offshore. Take KeepTruckin, makers of Fleet Management Software. They have an expansive SMB sales team in Pakistan, where the cost of a salesperson is much, much lower than in the United States, who are charged with handling smaller opportunities from US-based mom and pop trucking companies with one, two, or three trucks (KeepTruckin’ also has a US-based sales team in Nashville for managing larger prospects). They get the benefit of higher human-assisted conversion while keeping their costs lower.

When should I add a salesperson to the mix?

Assuming that you’ve decided you meet the criteria above, and believe you will benefit from involving people in your sales motion, the next question becomes when to start doing so.

The good news is there are pretty helpful signals to indicate that now is a good time to start. First, make sure that you have a “Contact Us” or “Contact Sales” call to action on your home page in a place that wouldn't distract the user from self-sign up, but at least discoverable enough such that if someone was looking for it, they could easily find it.

This is how you’ll start to see if you get inbound requests asking for help with “commercial conversion.” Like “Hey, finance would like us to put this on an invoicing relationship” or “What’s your SOC 2 situation?” or “We have a couple of different teams that we need to consolidate into one billing relationship.” As you start seeing more of these come in, maybe one or two a week, now’s probably the time to dedicate someone to handling those – a salesperson!

Now, obviously one or two inquiries a week isn’t exactly a full-time job, but it’s an indication that there are likely recurring needs like this in your existing customer base. For each user who raises their hand for help, there are probably ten other users who have the same pain point. So once you have that person in seat, handling those inbound inquiries, they can also start going outbound (“warm outbound”, versus pure cold outbound) into the customer base to determine if they can proactively help with some of these issues (and, perhaps, expand your offering within the customer’s account).

Having someone handling these requests is almost a two-for-one: Inbound inquiries help indicate that you need someone helping with commercial transactions, and their extra bandwidth (to start) can be used to start proactively engaging customers where your solution has an initial foothold to further penetrate the organization. For example, if Command E is seeing that a handful of salespeople are using the tool in a 200 person sales org, and then proactively engaging with those users (plus others) to see if they can do some personalized demonstration could help the rest of the sales org.

The second case for involving sales – raising conversion rates for accounts that are “worth it” – is a little trickier. If you’re like RevOps, and the cost of the software is such that it’s worth engaging pretty much any qualified user signup that abandoned, well, you would start doing this from day one. If you’re more in the realm of a Snowflake, Datadog, Mixmax, and others, where you can have individuals signing up for $99 a month, who would happy to stay at that level forever, mixed in with people signing up who may be starting at $99 a month but could represent an organization who could scale up to tens of thousands of dollars a month, well, we have to figure out a way of differentiating between these groups.

The good news is that you may already be getting low-tech indications that there could be a place for sales via the “Contact Us” information above. If Lockheed, Boeing, and General Motors all have registered a Contact Us request...well, that’s probably a good bet that Airbus, Ford, and Tesla have started a signup flow and abandoned. If this is the case, it’s probably time for us to get more proactive about knowing when a highly qualified lead comes through signup. I talk about this in the Early Inbound Marketing chapter of Founding Sales. There are a few ways to approach this. One way is to add some fields to your initial signup form that helps characterize the potential value of an account. For example, Snowflake asks for a user’s Title and Company name on signup, which can be used to make a judgment about the potential value of the user signing up (“Software Engineer” vs. “Director of Data Infrastructure'').

Datadog, on the other hand, doesn’t ask for the user’s title, but does ask for a Company name, and also ask for a Phone number - even though it’s not required (some people want you to call them! I promise!).

With this information in hand, we can do some smart things. Even something as basic as pinging an internal email listserv or Slack channel with new signups, so a person can see them makes a big difference. Later, you can get more advanced with programmatically sorting new signups based on observable factors (title, company size) and behavioral factors (if they completed the signup or abandoned it) to quickly differentiate between needles and haystack, and focus in on the needles - the “Directors of Data Infrastructure” from Tesla, while letting the lower value intensity signups be handled by our “tech touch” maturation efforts (emails, in-app messaging, etc.).

The even more advanced version of the above is using form enrichment from providers like Clearbit to match a signup email to a composite profile associated with that email address, and thereby potentially not have to ask, or, allow us to add additional information (e.g., company size) without having to extend our form, and thereby injure our conversion rates.

How do I set myself up for success during the transition?

Once you’ve decided the time is right to add salespeople to assist your self-serve product, there are a few key items to ensure you get it right. First, figure out if the initial focus of this salesperson will be:

“Scooping up” pods of successfully activated customers in large organizations and facilitating expansion in those accounts, OR

Helping with the conversion of unactivated customers.

Your initial focus is likely determined by the same information that told you it was time to start involving sales. If you’re, say, Zapier, and you keep seeing duplicate instances showing up in larger organizations, you might focus on the “scooping up and expanding” motion. Alternatively, if you’re Datadog, and you see registrations from really compelling logos showing up in the signup logs, but never turning on data flows, you might focus on the “help with conversion” motion. This isn’t to say that you can’t have both motions concurrently, but given that you should be approaching this as an experiment to start, better to focus on one, get that right to start, before moving on to validate the other.

First, do it yourself

One key part of starting things off right is to prototype this sales motion yourself, as the founder or product manager. This is something I talk about quite a bit in my book on sales for founders. As a foremost expert in the problem space you’re addressing, you’re best positioned to have the first few dozen of these sales conversations. In part, this is because you know way more about the market and the product than any salesperson you will hire, and secondarily, as you start adding a human element to your sales motion, you will invariably quickly discover new product requirements. Given that product requirement gathering is typically best done by a business founder initially, or someone who works on the product like a product manager, it’s best to have those people having these initial conversations. Later on, these sales tasks will be handed to a specially hired salesperson but usually only after the initial motion has been at least roughed out.

Provide data insights for sales

The next thing you’ll need is the insights to do sales well. Which means at least basic analytics. If you’re focusing on “scooping up pods” and expanding into organizations, then analytics or alerting that notifies you, proactively, to the fact that a larger organization has multiple successful instances of your offering deployed will be key. Note there are two things here - one is being able to see where there are multiple instances, and the second is the ability to see success, as indicated by heavy usage and feature adoption.

Similarly, understanding which of your successfully deployed customers are situated in much larger organizations could be fertile ground for expansion and thus help you prioritize which of these pods you’d like to go after first. Sometimes this can be intrinsic to your product. Most users of Command E sign-in with Google Apps to allow the product to index their GDrive and Gmail. What’s neat is that with this API access, Command E can also query how large that user’s larger organization is. Bigger organizations mean potentially more Command E users, and thus perhaps a juicy target to engage for expansion. When someone turns on Sonar to instrument their Salesforce instance, Sonar can quickly see how many total users are in that Salesforce instance, how many of them have admin rights (typically correlated with the number of eventual Sonar users), and how many tricky automations are already built in that Salesforce instance, which is correlated to the amount of value Sonar offers to a customer.

If you can’t get this data intrinsically from your product, then it’s definitely worthwhile to do some basic enrichment work via APIs like Clearbit. First, consider removing the ability for a user to sign up with a personal email address (or, at least making it non-default and higher friction) to help with your enrichment efforts. Even just having eyes on a domain can help you prioritize which accounts would be best to engage with. Second, enrichment providers can give you the size of the organization that a given user is associated with in their database. Bigger organizations are typically better when it comes to proliferating a successfully “landed” self-serve customer to “expand” more broadly in the account.

The key insights needed for the “conversion assist” sales motion are a bit more involved. In this case, it will be important to understand not just the potential total value of an account as signup (using methods described above), but also the persona of the user signing up. This can be as easy as adding a “Title” required field to your signup form. Understanding when you have an inbound lead who potentially represents substantial purchasing authority is a powerful thing.

As an example when I was researching this piece, I was rather surprised that New Relic’s signup page doesn’t provide them with additional information as to “how valuable” the person signing up might be. Whereas Snowflake’s (as shown above) certainly does in the form of the “title” field.

Enrichment providers can help here too, by passing back a current title for a given email address if you get a hit. Usually, it’s better to just ask for it, even if you’re afraid it’ll reduce signup conversion.

Next, understanding how “activated” users are helps with both the “pod scooping and expansion” case and also the “conversion assist” case. How activated a user gets can show which potential users might need intervention (again, based on their potential value to your organization - large accounts and valuable title), and also where you have pods of highly activated users in larger accounts to prioritize.

You likely already have existing indicators of activation with respect to your product - how far someone got through signup, how many features they are using, and how frequently they’re using those features. Now we need to get that information into the hands of the people who will be prioritizing which hung users, or which pods of activated users to engage.

At Atrium we use software called Census to help us pipe user activation data into our CRM (Salesforce) such that sales staff can easily consume this information and act accordingly. We’re pretty far down this process, but to start you could use any of your existing product analytics for this – whether that’s Amplitude, Pendo, Mixpanel, Heap, etc. Think for a second about what that reporting would look like: new users in some trailing time period, their activation status, per user, their “account desirability” information, their “user desirability” information (e.g., title), and their contact information. Also, all accounts, grouped by domain (ideally) in order to easily show which organizations have meaningful pockets of activation in them. Ideally, you pipe that information into a go-to-market system like your CRM or marketing automation platform and can start doing business logic against it (to protect engineering resources for product work), but giving your salespeople logins to your product analytics tool can be ok to start. We just want to get it somewhere where the person working on this initial sales motion can consume it, maybe lightly manipulate it, and definitely act on it.

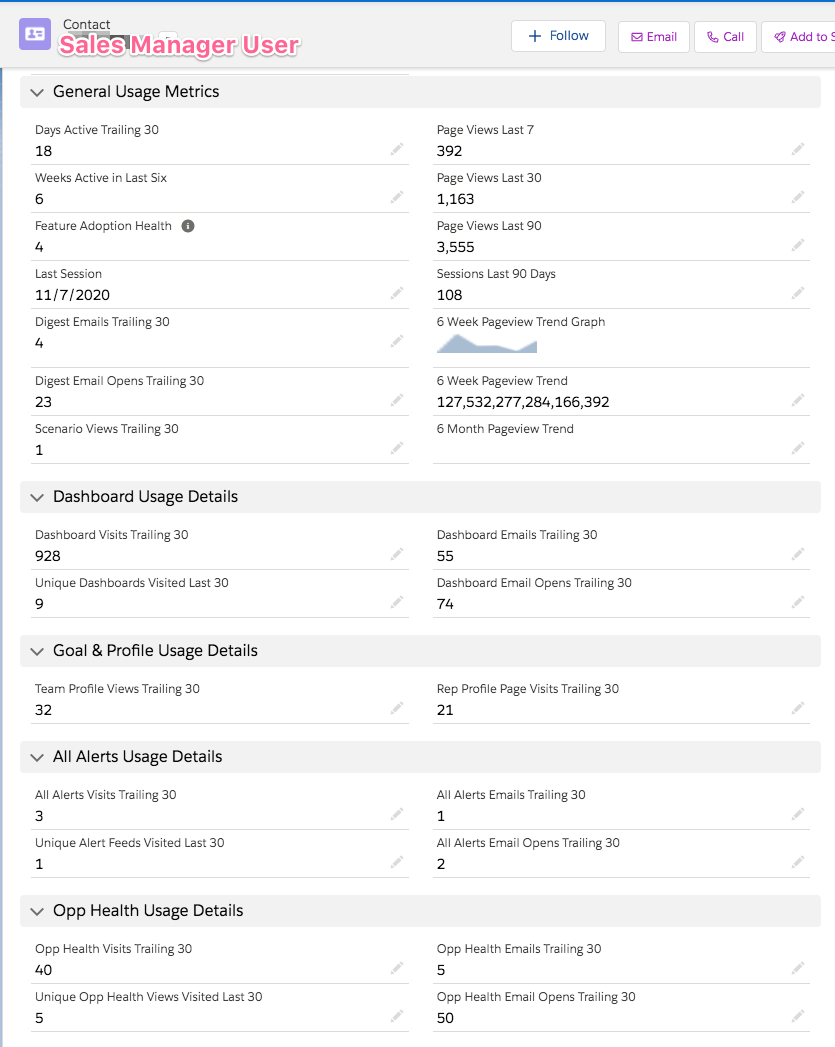

As an example of where you can eventually end up, this is what a Salesforce contact object page looks like at Atrium, as a result of about a year of tuning and additions as we got more sophisticated on user activation instrumentation. But even just starting with the last login and total pageviews or actions on a given time interval can be a great start.

The same approach applies to alerting. You can push alerts into an email listserve or Slack channel based on certain desirability criteria (“Badass account signed up and didn’t activate!” vs. “Badass account reached awesome activation threshold!” vs. “Account reached critical mass of multiple activated users!”). At Atrium we have email alerting on initial user signup that fires an email to a list-serve and a lead to Salesforce, both of which feature user name, email address, company name, title, size of account (after user sign in with Salesforce we can interrogate the size of their Salesforce user table, which correlates to magnitude of the account), and how far through initial activation they got.

Similarly, we have alerting set up using workflow rules and triggers in Salesforce to send pertinent alerting to relevant listserves when users get beyond certain thresholds of activation (“OMG, this user has hit X threshold of feature breadth use and Y threshold of page views in the trailing Z period.”) Once alerted, sales staff use this information to engage the user as relevant (“Wow, it’s time to buy!” or “Wow, you have a bunch of folks getting a ton of value out of this. Let’s roll you all into the same account, eh?”)

Is it working?

Lastly, since the initial involvement of humans in your commercial motion is an experiment until you’ve validated it’s working, you’ll want to set yourself up to be able to understand just that: is it working? There’s a lot more on this topic in the section from Founding Sales on “Early CRM”, but at minimum, you’ll want some sort of system by which to record the number and state of these early sales conversations. This is typically a CRM of some sort, but even something as basic as Airtable can work. The reason you want to do this is to not just help yourself keep all these parallel conversations straight (in sales, you have to record everything), but also to score the results of your efforts: are we actually getting expansions done? Are we actually getting highly valuable accounts converted? How many of these conversations are we having? What proportion are we winning? More on this in the “Sales Performance Instrumentation” section of Founding Sales, but you want to make sure you’re capturing enough information so you can be honest with yourself as to how it’s actually going.

Common pitfalls to avoid

Regardless of how well you set yourself up for success, there are a number of pitfalls you’ll want to avoid.

1. Having someone else do sales

One of the things I passionately believe is that founders should be their own first salesperson. Founding Sales was written based on this belief – to make it way easier for founders (or product managers) to do so. Assigning this task to someone else is fraught with downsides, as they won’t have the same product acumen as the founder by which to have productive sales conversations, they won’t be good at product requirements collection as new features crop up needed to facilitate larger contracts, and so on. Yes, it’s a lot of work, but it’s worth it for it to be you, at least to start. Also, you have a huge advantage – you’re the founder/product manager. That’s really cool to users. They want to talk to you. When the Command E founders reached out to my sales reps, they thought it was the raddest thing ever - “The founder of Command E, this product I totally love, wants to talk to little old me?!”

2. Not starting

A variant of the above is having indications that sales involvement in your growth strategy would make sense, but kicking the can down the road because you’re afraid of it. Selling is not magic, it’s not rocket science, and anyone can learn to do it. Don’t psych yourself out that it’s a huge lift. Adding sales involvement to your commercial motion is no different than adding new features to your product – you can start with a minimum viable approach to experiment, and start iterating yourself towards success. But you do have to start.

3. Going top-down

There will likely be a point in the future when a “top-down” motion – where a salesperson starts engaging at the top of an organization with no existing user relationship with your product – will make sense to add your growth motion. Now is not that time. Your current strength and asset is that you have a self-serve product that users love. A top-down motion will mean interacting with decision-makers who are so far removed from the day to day work your product facilitates, they will have far less understanding of why it’s helpful and valuable. Moreover, they’ll likely have all sorts of conceived product requirements that don’t matter a lick to your users but will gate any sort of commercial progression, typically based on advanced features that incumbents have. Slack and Zoom currently have enterprise account executives talking “digital transformation” with CIOs of massive companies where not a single person uses the product. Now is not the time to do that for your offering.

4. Not allocating product resources

You might think that adding direct sales to a self-serve commercial motion is just about adding people to the mix. It turns out that what actually happens is you start adding incremental “users” to the mix too – they just aren’t end-users. These incremental user personas will have different needs than your existing users, and some of those needs will require new features to satisfy. It will be important to allocate engineering resources to address these needs, otherwise, you may find that your direct sales efforts will be less successful. Moreover, some of these features will be wholly unsexy - like Single Sign-On support, or security credentialing, like SOC 2 or ISO 27001, and more. But these features will end up being important, as their absence will block the sales-assisted use cases you’re seeking to unlock – whether that’s “account merge”, to allow the rolling up of a bunch of disparate self-serve users in an overarching company, or “conversion assist”, where your lack of security credentialing means that a large, prestigious, and commercially attractive account won’t start sending data to your offering.

5. Lenny likes lists of 5

This is here because Lenny said I should always have either three things or five things in a list 😆

Once you have started and are on your way, you’ll eventually want to hand sales off to a dedicated resource. The hiring and management of dedicated salespeople to continue the beginnings of this “sales-assist” motion is beyond the scope of this article, but the chapters on sales hiring, sales onboarding, and early sales management chapters of Founding Sales tackle these topics in-depth.

In summary

Layering a rigorous direct sales motion on top of an existing, successful self-serve commercial motion can hypercharge what is already a successful self-serve business. Similarly, foregoing a direct sales motion can leave important parts of the competitive landscape open for other players to eat your lunch. Adding sales to your existing self-serve approach isn’t for every case - but if it is, it can be a huge advantage. The good news is doing so shouldn’t be mysterious, and the guidance above should get you started on your journey. If you want to get deeper into the nuts and bolts of selling, my book on startup sales, Founding Sales will be a great resource for you. Happy hunting!

🔥 Job opportunities

Product: Aavia, ClassDojo, Descript, KUDO, Hipcamp, Papa, Roofr, Prenda

Growth: Coda, Instrumentl, Levels, Prenda

Design: Ashby, Cascade, Office Hours, Runway, Stytch, Watershed

Engineering manager: Cerebral

Backend engineer: Coda, Sourcetable, Transform

Fullstack engineer: Cascade, Centered, Cerebral, Icebreaker, Iggy, Primer, Runway, Snackpass

Is there someone in your life who would benefit from this newsletter? Consider giving them a gift subscription 💖

Sincerely,

Lenny 👋

Wonderful post with a lot of insights for me as a PM at an early stage B2B startup.

I liked the point around seeing whether your product can fit in along with an existing inferior product.

And another point about going top-down too early. You have to be close to the users of the product.