👋 Hey, Lenny here! Welcome to this month’s ✨ free edition ✨ of my newsletter. Each week I humbly tackle reader questions about product, growth, working with humans, and anything else that’s stressing you out about work. Subscribe today to get each and every issue.

As a startup founder, you need to do the impossible. You build something that has never been built before, with a team that’s never worked together before, while learning dozens of new skills, making countless no-going-back decisions, all before you run out of money (and energy). It’s like being lost in the wilderness, in the dark, with only a vague sense of where you’re heading.

Imagine if you had a map.

From TikTok to Reddit to Uber to Airbnb, I’ve had the opportunity to study the growth stories of hundreds of companies. I’ve explored how these companies acquired their first users, found product-market fit, built growth engines, and nailed retention, conversion, virality, positioning, pricing, and most every other ingredient that goes into building a durable business. But I’ve never tied all of these pieces together.

Starting today and for the next five weeks, I’m going to share a six-part playbook that I’ve been developing that guides you through the six fundamental steps of kickstarting and scaling your consumer business. Later this year, I’ll share a similar playbook for B2B businesses.

This work is the result of hundreds of hours of research, interviews, and synthesis. It’ll include brand-new frameworks, stories, and insights that I’ve never before shared. It may be the best work I’ve ever done. If nothing else, it’s definitely been the most time-intensive.

Here’s what’s in store:

Step 1: INSIGHT: Come up with your idea ← This post

Step 4: REACH: Find your early adopters by doing things that don’t scale

Following these steps (or any steps!) won’t guarantee success—but it’ll certainly increase your odds.

Let’s dive right into Step 1.

Whether it’s disappearing photos, cars on demand, DVDs by mail, or a marketplace for NFTs, it all starts with an idea. And as much as you’re told that ideas don’t matter—don’t buy it.

“I myself used to believe ideas didn’t matter that much, but I’m very sure that’s wrong now.”

—Sam Altman

To kick off this series, I dug into how 50 of today’s most successful consumer businesses originally came up with their startup idea. Below I’ll share:

The five most common strategies for coming up with a startup idea

Should you sit around and think, or wait for an idea to strike?

What signs point to it being a good idea?

What to do once you have an idea

This post also includes the largest collection of startup founding stories you’ll find anywhere.

Before we get into strategies, a few takeaways (and surprises) from my research:

High-level takeaways

These consumer founders were very young. Half were under 30 years old when they started the company, and 80% were under 35.

Less than a third of consumer startup ideas emerged out of founders trying to solve their own problem. I was expecting this to account for the majority of startup ideas.

Less than a third of founders were actively ideating a startup idea when they came up with their big idea. In other words, most startup ideas emerged organically.

Only 18% of winning consumer startup ideas came from pivots—I was also expecting this to be much higher.

Less than a third of founders had a unique or specific skill that enabled them to build their product.

Just over half of the biggest consumer business ideas felt very trivial at the time, e.g. Twitter, Snap, Pinterest, Coinbase, Tinder, Calm, Airbnb.

Over 75% were founded by 2+ founders.

68% had an engineering co-founder.

42% had previously started a company.

11% of founding teams had a co-founder with an MBA.

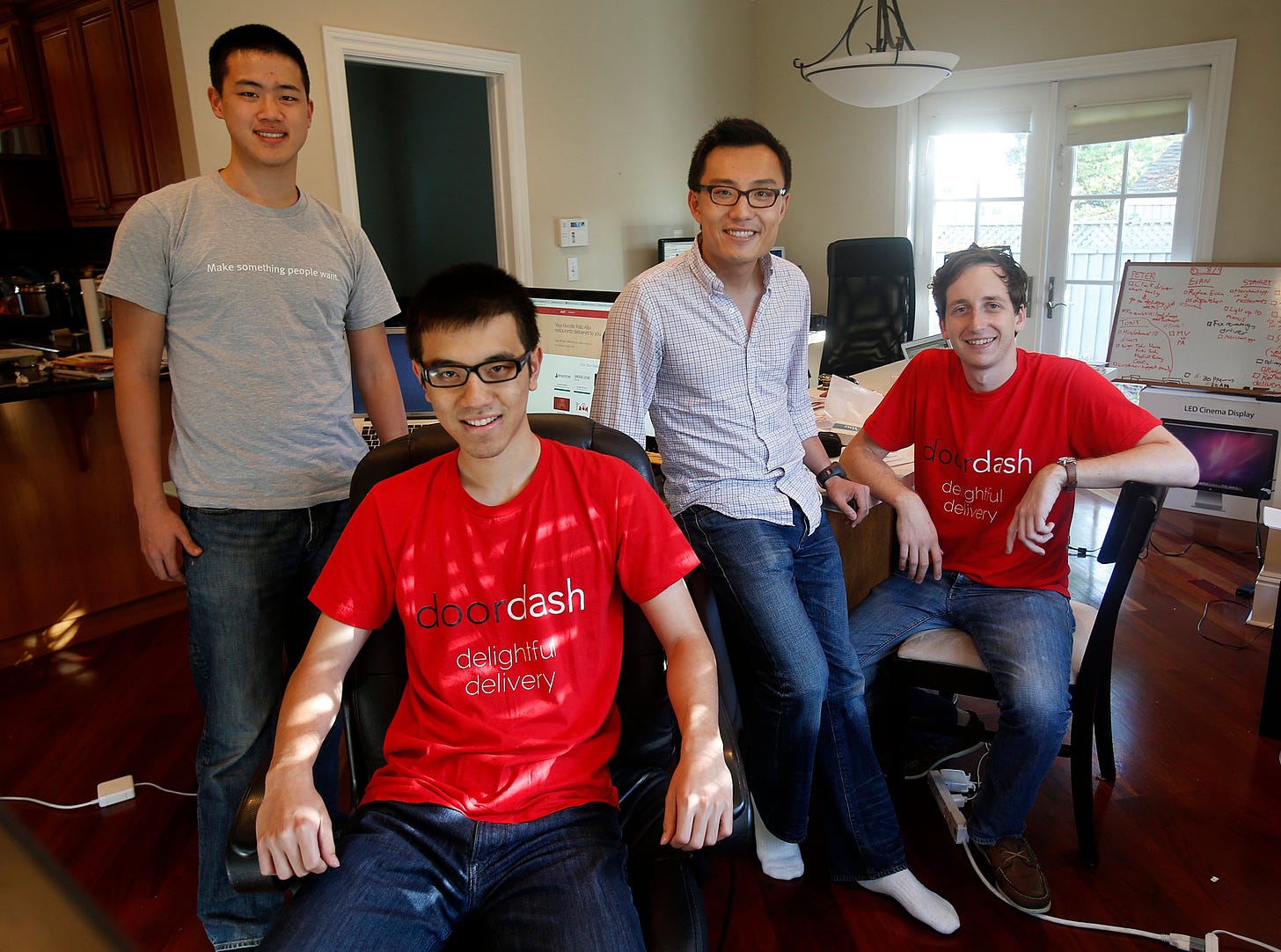

Only one company, DoorDash, came up with its idea by actively talking to potential customers/users.

You can see the analysis I did in this Google Sheet.

How to come up with a startup idea

Based on my research of over 50 of the most successful consumer companies, there are only five common strategies for coming up with a great startup idea—all rooted in paying attention:

Pay attention to your own problems, and solve them (~30%)

Pay attention to your curiosity, and tinker (~20%)

Pay attention to what’s already working, and double down (~18%)

Pay attention to paradigm shifts, and work backward (~15%)

Brainstorm with friends, and pay attention to the four points above (~15%)

Here are these strategies mapped to today’s biggest consumer businesses:

Below, I explore each strategy in depth and share the founding stories from each of these companies. Let’s get into it.

Strategy 1: Pay attention to your own problems, and solve them

The largest chunk (~30%) of successful consumer companies emerged from the founders simply solving their own problems—and then realizing that their solution was valuable to others.

For example:

Dropbox: Drew Houston kept losing his thumb drive, so he built cloud-based file syncing.

Etsy: Rob Kalin was looking for a way to sell his furniture and couldn’t find anything good.

Cameo: Steven Galanis and Martin Blencowe needed to find business for their NFL client, so they experimented with pay-for-access to celebrities.

Airbnb: Joe Gebbia and Brian Chesky needed to find a way to pay rent, decided to rent their air bed to travelers, and found that people enjoyed the experience.

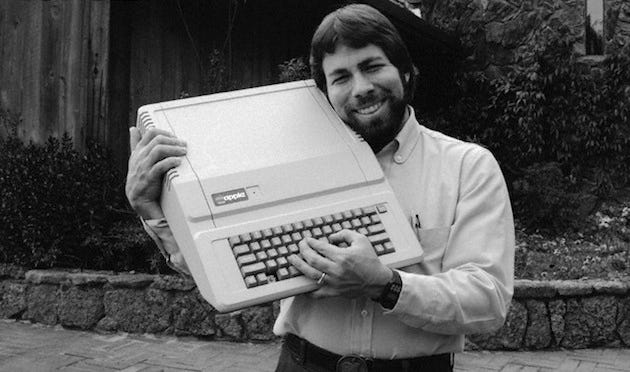

Apple: Steve Wozniak couldn’t find a computer he was happy with, so he built his own.

Substack: Chris Best and Hamish McKenzie were worried about the direction content and journalism were heading in, so they decided to build a solution themselves.

Uber: Garrett Camp was frustrated by his inability to get around San Francisco reliably and began experimenting with better solutions.

Hipcamp: Alyssa Ravasio struggled to find great campsites, so she built a website to make that much easier.

Snapchat: Reggie Brown wanted to send private photos without worry, so he recruited Evan Spiegel help him built an app that sent disappearing photos.

GOAT: Daishin Sugano got ripped off with fake Air Jordans, which got him thinking about a better solution.

WhatsApp: Jan Koum wanted a simple way to know what his friends were up to.

Warby Parker: The founders kept losing their expensive glasses and realized there had to be a way to make them cheaper and easier to order online.

Calm: Michael Acton Smith found that meditation helped him deal with his pain.

As Paul Graham says, “Pay particular attention to things that chafe you.”

Below are stories from these founders sharing how they overcame a problem they were facing, and how that helped them realize there was an opportunity to start a business.

Dropbox

“I got really sick of having to carry my thumb drive everywhere, and if it wasn’t a bus ride I was getting on, I was about to put in the washing machine—it’s always one step away from disaster. And then I was on a ride from Boston to New York, forgot my thumb drive, and I couldn’t get any work done and started writing the first lines of code for what became Dropbox, even though I had no idea where that was gonna go at the time.”

—Drew Houston, CEO and co-founder, via foundr

Etsy

“I started my own company with woodworking and I was making these couture computer cases, and I looked for the best way to sell those. I looked in the offline world, where there’s consignment and there’s wholesaling, and neither of those were really my cup of tea. I also looked at the online world and neither of those really worked out.

And then the magical moment happened when I started working with Jean Railla, who was the creator of Get Crafty.... She asked me to help her rebuild Get Crafty. That was my introduction to designing websites.... I was looking to sell my own furniture, and so that idea percolated and I talked with Jean about adding a marketplace to Get Crafty. She said, and I probably agreed with her, that it would probably be better to start the marketplace separate instead of doing it inside of Get Crafty, because Get Crafty was really a community of people talking, so one thing led to another and the idea of creating the marketplace as a marketplace took birth.

And when I initially started Etsy, my thinking was I’ll build the marketplace where I’d like to sell what I’m making, and then I’ll get right back to making these things.”

—Rob Kalin, co-founder, via From Scratch

Cameo

“The way the company started was Steven and Martin [co-founders] were chatting at a funeral, and Martin was talking about how we recently became an NFL agent managing Cassius Marsh and the challenges with trying to find him brand deals, etc.

They decided to start a company where for X dollars you can do Y activity with Z athlete. For example, go golfing with Michael Jordan, invite Serena Williams to your daughter’s birthday, etc. The specific problem that Cameo was solving was Martin’s problem to get cash paid. At first.”

—Devon Townsend, CTO and co-founder

Airbnb

“I get to San Francisco and Joe tells me the rent is $1,150. And I don’t have enough money to pay rent. It turns out that weekend, though, an international design conference was coming to San Francisco. And all the hotels in San Francisco were sold out. And so that’s when we had this idea. We said, ‘Well, what if we just turned our house into a bed and breakfast for the design conference?’

Unfortunately, I didn’t have any beds, but Joe had three air beds. So we pulled the air beds out of the closet. We inflated the air beds and we called it airbedandbreakfast.com.

When we came up with this idea, I remember telling my mom, like, ‘I’m now an entrepreneur.’ And she said, ‘No, actually you’re unemployed.’ ”

—Brian Chesky, CEO and co-founder, via The Jordan Harbinger Show

Apple

“I didn’t want to pay to use somebody else’s computer, so I decided to design my own. I wanted to have it all in one place, and I already had a terminal, so I was partway there.”

—Steve Wozniak, co-founder, via Byte magazine

Substack

“The way it all started was through conversation between Chris and I. Chris was writing a draft of a blog post that he never ended up publishing. In the draft, he laid out all the problems with the attention economy, how it incentivized bad online content and behaviors that led to bad outcomes in society. He asked me for feedback on that draft, and I said all the things he was saying were true but that people in the media already knew those were the problems and what they were lacking were any meaningful solutions (not for want of trying).

I suggested that he add a couple of paragraphs proposing a better way forward, but instead of doing that he started trying to convince me that we should make a thing based on direct payments between readers and writers because that would better align incentives between all parties.

We were both readers of Stratechery and had heard Ben Thompson saying the model was working great for him and he didn’t know why more people weren’t trying it. We wondered what might happen if it were far easier for any writer to try to do what Ben was doing, since the effort required to set up and maintain all the infrastructure to run something like Stratechery was nontrivial. And that’s when we started brainstorming.”

—Hamish McKenzie, co-founder

Uber

“The city’s sad taxi situation seriously cramped [Garrett Camp’s] new lifestyle. Since he couldn’t reliably hail a cab on the street, he began putting the yellow cab dispatch numbers in his phone’s speed dial. Even that was frustrating. ‘I would call and they wouldn’t show up, and while I was waiting on the street, two or three other cabs would go by,’ he says. ‘Then I’d call them back and they wouldn’t even remember that I called before.’

Habitually restless and frustrated by inefficiencies, he came up with his first attempt at a solution: he would call all the yellow taxi companies when he needed a cab. Then he would take the first one that arrived.

Not surprisingly, the cab fleets didn’t like that tactic. Though impossible to confirm, Camp believes his mobile phone was blacklisted by the San Francisco taxi companies. ‘They wouldn’t take my calls,’ he says. ‘I was banned from the cab system.’

Camp started to experiment with the city’s ‘gypsy cab fleet’—the unmarked black sedans that would approach prospective passengers on the street and flash their headlights to solicit a fare. Most San Franciscans, particularly women, would stay away from these unmarked cars, fearing for their safety or worried by the ambiguity of a cab without a running meter.

But Camp found that a majority of the cars were clean and that many of the drivers were friendly. The biggest problem for these drivers was filling in the dead time between rides, when they tended to wait outside hotels. So Camp started collecting the phone numbers of town-car drivers. ‘At one point, I had 10 to 15 numbers in my phone of the best black-car drivers in San Francisco,’ he says.

Then he started gaming the system further: texting a favourite driver hours before he needed him and telling him to meet him at a restaurant or bar at an appointed time. On another night, he rented a town car and driver for himself and a group of friends for an entire evening. It was an indulgence that cost $1,000, and zooming around the city at the end of the night dropping everyone off was a pain.

And that is when the futuristic image from Casino Royale popped into Camp’s head. Suddenly, he was obsessed with a new notion. He frequently talked with McCloskey [his girlfriend] about the idea of an on-demand car service and vehicles that passengers could track via a map on their phones. At one point that year, Camp scrawled the word ‘Über’ into a Moleskine notebook that he kept to jot down new ideas and logos for companies and brands.

Camp was certain that he wanted such a service. He also knew that the iPhone and its new app store, which Apple introduced over the summer of 2008, were going to finally make the futuristic vision in Casino Royale practical. Not only could you chart the location of an object on a map, but since the earliest models of the phone had an accelerometer, you could also tell if the car was moving or not. That meant that an iPhone could function like a taximeter and be used to charge passengers by the minute or the mile.

The idea behind Uber was crystallising in Camp’s mind.”

Hipcamp

“I was planning my first camping trip. I had been camping a ton before, but always with someone else doing the work, making the reservation. I couldn’t believe how difficult the process was. Everything was on so many different websites. So much was booked out. The information was super-fragmented.

Finally I found a campground. We got down there and it was great. I walked out to the ocean and everyone was surfing. It turned out this place was a great surfing spot. I had read everything about the campground online, everything on their website, and nowhere had mentioned surfing. And I love to surf! I just sat there looking at this beautiful wave breaking and realized I had tried so hard and still missed what was the best part of this campground experience. I was driving back the next day when the idea came to me that getting outside was very broken, and that the internet could fix it.

I learned how to program later that year. That June, I launched a very, very beta version of the website.”

—Alyssa Ravasio, CEO and founder

Snapchat

“Reggie Brown [co-founder] carefully ran his fingers over the blunt, admiring its tightly rolled perfection. It was almost a shame to smoke such a work of art. […] The subject of the conversation moved on to the girls. A dreamy expression appeared on Reggie’s face. ‘I wish I could send disappearing photos,’ he mused, almost absentmindedly. […]

Reggie focused on the usefulness of this new idea. A way to send disappearing pictures. He wouldn’t have to worry about sending a hookup a picture of his junk! And girls would be way more likely to send him racy photos if they disappeared.

Suddenly, he jumped up, and rushed down the hall to see if Evan [Spiegel] was around. Bursting into Evan’s room, Reggie exclaimed, ‘Dude, I have an awesome idea!’ Even before Reggie finished explaining his idea, Evan lit up. He was immediately energized—almost intoxicated. It was just like all those nights of partying together, except they were drinking in Reggie’s idea. ‘That’s a million-dollar idea!’ Evan finally exclaimed.”

—Billy Gallagher, How to Turn Down a Billion Dollars

GOAT

“When the [Air Jordan 5 Grapes] arrived [from eBay], I was so excited; I immediately opened the box and smelled them. There’s a very distinct Air Jordan 5 smell, and it just wasn’t there. When I put the shoes on, they didn’t feel right. After buying a lot of the same sneaker style, you know what to expect when they’re in hand/on your feet. The details of the shoes and the Jumpman logo looked off, the pods in the back looked deflated, and the laces were even a different texture.

The purchase was my first pair of fake shoes, and it was a total letdown. And I wasn’t able to get my money back, because eBay has a poor policy for reconciliation that puts the burden on the buyer and seller to work out any issues. The experience really affected me, and for the first time I wasn’t excited to shop for kicks.

My co-founder Eddy and I talked about the experience and he started grilling me with questions:

‘Does this happen to a lot of people?’

‘Who did the best job outside of eBay?’

‘Is there anyone leveraging technology to solve this problem?’

‘How do people search for sneakers?’

It became apparent that the industry I loved was fragmented and unsafe. Many people buying sneakers were running into the same problems. There are entire subreddits, social accounts, and blogs built around how to spot fakes. People even post product SKUs in spreadsheets on forums like NikeTalk so others can find the shoes they are looking for. Essentially, everyone was piecemealing information together to find and purchase authentic sneakers.

We knew we could use technology to solve many of the existing problems, and with the knowledge we already had in the space, we would have an additional edge. We also decided it was important for us to find an industry that serves a passionate and youthful generation. GOAT fit the bill, and we knew we were onto something. We just needed to start building.”

—Daishin Sugano, co-founder, via Matrix Partners

WhatsApp

“ ‘Jan was showing me his address book,’ recalls Fishman. ‘His thinking was it would be really cool to have statuses next to individual names of the people.’ The statuses would show if you were on a call, your battery was low, or you were at the gym. […]

Koum spent days creating the backend code to synch his app with any phone number in the world, poring over a Wikipedia entry that listed international dialing prefixes—he would spend many infuriating months updating it for the hundreds of regional nuances.”

—Alex Fishman via Forbes

Warby Parker

“[Right before starting business school], I had accidentally left my glasses on an airplane and they’d cost me $700. And I just couldn’t justify as a full-time student paying that much for a new pair of glasses. The new iPhone 3G had come out that we didn’t mind at the Apple Store paying $200 for, and it did all these magical things. And meanwhile, the technology behind a pair of glasses is 800 years old, and it just didn’t make sense. […]

I was complaining to anyone that would listen about why glasses were so expensive. And then Andy kept losing his glasses, and he was buying everything online but couldn’t figure out why he couldn’t buy new glasses online and why no one was effectively selling glasses online. So we kind of started this conversation where we were kind of frustrated by different pieces of the eyewear industry.

We knew that Neil [co-founder] had spent a number of years working for an eyewear nonprofit and probably knew a lot more about this than we did. And so we were all in the computer lab one day and started asking Neil a bunch of questions, and, no pun intended, but I think all our eyes were open that there was this massive opportunity. We thought, oh, why not sell glasses? And the light bulbs went off in all of our minds.”

—Dave Gilboa and Neil Blumenthal, co-founders, via How I Built This

Calm

“I just couldn’t face going into the office every day…. I used to take painkillers every morning because I woke up with such a headache and my body ached, I felt like I was hit by a truck every morning. So these painkillers would kind of help me get started in the day. It was a very tricky time, so not addressing the fundamental issues with my business, or trying to but not doing a very good job—for me this is what led to Calm, because I could see it so clearly having been through it. One of the best businesses to ever set up is one where you’re scratching your own itch, and I didn’t know what meditation was or mindfulness, but my very dear friend Alex Chu had been meditating with CD-ROMs he bought when he was a teenager (a very unusual teenager), and he would often say to me, ‘Look, dude, you need to try meditation,’ and I’d be like ‘You need to try effing off. That’s the last thing I need. Give me something practical.’

But slowly but surely, the penny started to drop and I kind of got it, and the key breakthrough for me was when I did something I’d never done before. I took myself off on a solo holiday. I went away to the Austrian Alps, to this resort where I played tennis in the morning, I scribbled in my notebook, I read books, and I started to try to meditate because I’d heard about it, and it was just incredible. The fog started to clear; I’ve had my face pushed up against the cliff and I couldn’t see a way out of this problem that I was facing with my business, and just taking a step back and getting perspective was hugely valuable. And I read a bunch of books and research papers and I realized that you know, this is science: mindfulness is a way of rewiring the human brain. What if we could make this simple and relatable and accessible to everyone? This could be one of the biggest opportunities and businesses in the world.

I came back, I remember chatting to Alex about it, and he was like ‘Right, dude, you finally get it. Let’s go.’ […]

He found a person that owned calm.com […] and I said, ‘Oh my god, what a great domain, what a business we could build there, helping the world become more calm.’ I said, ‘How much is the domain?’ And he said, ‘It’s about a million pounds,” and I said … ‘Right.’

About a year later, we’re playing video games and he said the guy that has calm.com wants to to sell it and he’s willing to to do a deal. We were able to buy it for much, much less… So we bought calm.com, and that was kind of the starting acorn that was planted for that business.”

—Michael Acton Smith, co-founder, via The Diary of a CEO

Advice for finding startup ideas by solving your own problem:

Build your self-awareness: Pay attention to challenges you have day to day.

Be motivated: Pay attention to problems that drive you to action.

Don’t take your ideas for granted: If you’re finding it valuable, it’s likely other people will too.

Strategy 2: Pay attention to your curiosity, and tinker

Twenty percent of the biggest consumer businesses emerged out of the founders simply following their curiosity and intuition and then spending time tinkering with the idea. In most cases, soon after they had the idea, they quickly built a prototype to see if there was a there there.

For example:

Coinbase: Brian Armstrong got excited about the applications of crypto and decided to build a Bitcoin wallet.

Google: Larry Page and Sergey Brin got interested in the web for its mathematical characteristics and built a crawler to rank pages.

OpenSea: Devin Finzer got excited about what the new ERC721 standard made possible and shipped a beta of OpenSea in a couple of months.

Musical.ly (aka TikTok): Alex Zhu noticed teens combining video and music and quickly built a prototype.

Twitter: Jack Dorsey got excited about building a way to send simple status updates to friends and built a prototype in two weeks.

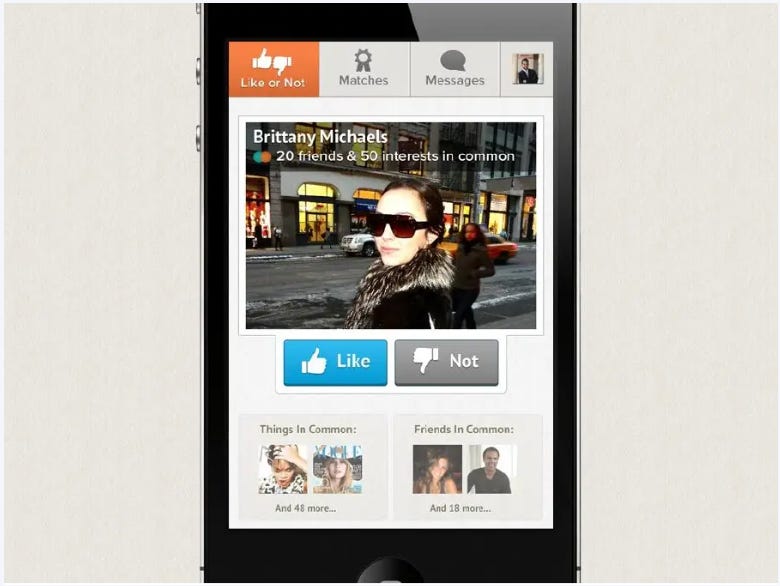

Tinder: The early team built a prototype at a hackathon and couldn’t stop working on it.

Duolingo: Luis Von Ahn started exploring language learning academically and got excited to see if he could build it into a business.

Rent the Runway: Jenn Hyman’s sister told her she wanted to wear a dress once, mostly for the photographs, but still had to buy a new dress.

The RealReal: Julie Wainwright’s friend bought upscale consignment while they were out shopping, and she recognized that it could be done much more effectively online.

“A good way to trick yourself into noticing ideas is to work on projects that seem like they’d be cool. If you do that, you’ll naturally tend to build things that are missing. It wouldn’t seem as interesting to build something that already existed.”

—Paul Graham

As Steve Jobs said, the reason people have to have a lot of passion for what they’re doing is because “if you don’t, any rational person would give up. If you don’t love it, you’re going to fail. So you’ve got to love it, you’ve got to have passion.”

Here are the stories from founders who found their way to a massive business through following their curiosity:

Coinbase

“I happened to see [the Bitcoin white paper] on Hacker News. I was just sort of reading things on the internet…. I don’t claim to have understood it the first time I read it, but I did have a degree in computer science and economics, and something about it grabbed my attention. I distinctly remember reading it and thinking, wow, this might be the most important thing I’ve read in like five years. […]

And then at Airbnb, we were trying to operate in 190 countries around the world. There were delays; it was impossible to know how money was going to get moved in all these countries. And so I just had this sense that financial services are really holding back innovation in the world, and it’s holding back human progress because people don’t have the freedom to participate in this global economy, because of all the barriers to innovation.

Imagine if you could unlock the level of innovation or the kind of trust in security that a society like the U.S. has, but put that into 190 countries, just because they have good internet access, a cell phone, and now they have crypto. And what if I could help do that? That just got me incredibly excited.”

—Brian Armstrong, CEO and founder, via How I Built This

Google

“[Larry] Page didn’t start out looking for a better way to search the web. Despite the fact that Stanford alumni were getting rich founding internet companies, Page found the Web interesting primarily for its mathematical characteristics. Each computer was a node, and each link on a web page was a connection between nodes—a classic graph structure. […]

It proved a productive course of study. Page noticed that while it was trivial to follow links from one page to another, it was nontrivial to discover links back. In other words, when you looked at a web page, you had no idea what pages were linking back to it. This bothered Page. He thought it would be very useful to know who was linking to whom. […] Unaware of exactly what he was getting into, Page began building out his crawler.”

OpenSea

“Initially, the idea for OpenSea stemmed from our interest in CryptoKitties. While marketplaces for digital goods have existed for quite some time, they tend to be self-contained ecosystems: individual marketplaces for specific games, marketplaces for domain names, marketplaces for tickets, etc. Scaling something like eBay for digital assets would be difficult because there was little standardization around digital ownership. With the introduction of ERC721, it felt like such an idea was possible for the first time.

We validated the idea by joining the various communities for the new ERC721 project […] and shipped the first version of OpenSea within a couple of months, in order to get a product out there in the wild and start testing with early adopters.”

—Devin Finzer, CEO and co-founder, via DeFi Prime

Musical.ly (aka TikTok)

“I was on Caltrain one day, from San Francisco to Mountain View, and it was crowded by teens. Observing their behavior, 50 percent were listening to music and the other 50 percent were taking photos and videos with their speaker on top to add music. Teens are so passionate about social media, photos, videos, and music, that it made me think, ‘Can we combine these three very powerful elements into one app and build a social network for music videos?’ ”

Twitter

“Jack Dorsey grew up in St. Louis, and at the age of 14 he became obsessed with dispatch routing. That was something he wanted to write software for, so he got to work on that. He was in St. Louis and there were no bike messengers there, but he was obsessed with this, so he wrote open source software for dispatching, which to this day is used by many different taxicab companies. He had this routing history, and he had this idea from when he first started seeing the status messages in instant messaging and wondered, ‘What if we could build a status service out of that?’

So later, he came to us with this idea: ‘What if you could share your status with all your friends really easily, so they know what you’re doing? But you don’t want to have to write a whole blog entry or LiveJournal entry.’ At the time, we had been thinking about what interesting things we could do with SMS, because we were interested in it. And so we made the connection between status and SMS [in March 2006].

So we went off and built a prototype in two weeks and showed it to everyone in Odeo. They really dug it. We knew when Jack told us the idea it was a cool idea, but we built it and showed it to the team and everyone started using it. I think the first weekend we were using it, I was ripping up all the carpet in my house, having a terrible weekend, and my phone buzzed and I look down and saw that Jack was sipping wine in Napa. The idea that I was doing what I was doing, and I could look down and see what he was doing just struck me. ‘I can’t believe I know that,’ and it made me giggle that I knew that.”

—Biz Stone, co-founder, via MediaShift

Tinder

“About two weeks after Sean [co-founder] started work, he participated in a hackathon. Sean had been talking about potentially building out a dating product for a while, so the two [Sean and Joe Muñoz] were paired together based on the compatibility of their two passion projects. Over the course of the hackathon in February, they built the first prototype of Tinder.”

Duolingo

“The whole thing started as an academic project at Carnegie Mellon between me and my PhD student Severin Hacker. I had just sold my second company to Google, and we both wanted to work on something related to education. Education is very general, so we decided to concentrate on one kind that is in huge demand everywhere (except the U.S.): language education.”

—Luis Von Ahn, co-founder, via Quora

Headspace

“I was midway through a sports science degree when I left England and traveled to Asia to find some form of meaning, and I was eventually ordained as a Tibetan Buddhist monk after years of training. Ritually meditating four times a day, I became aware that many people outside this tradition didn’t know what meditation was, or had negative preconceptions about it....

I returned to England—in a suit and tie, rather than robes—and found a doctor who was interested in mindfulness. I worked in his London clinic, where I was introduced to an advertising executive, Rich Pierson. We clicked from the start and began doing a skill swap—me teaching meditation and him giving lessons in marketing.

Rich had amazing vision and saw the potential of what I was doing. He tried to persuade me to do an app—a very new thing at the time—which I thought was such a bad plan, so we launched Headspace as an events series in 2010. After receiving feedback that people had been inspired at our events but didn’t know what to do when they got home, Rich asked me to record some of the sessions. Almost three years later, those recordings became the main material of the app.”

—Andy Puddicombe, co-founder, via Soho House

Rent the Runway

“In the second year of business school, I went home for Thanksgiving, and I was in Becky’s apartment. And Becky had just gone to a store and bought a dress that was higher-cost than her rent. And as her responsible older sister, I remarked how she should probably wear one of the dresses in her closet again, as opposed to being in credit card debt. And her response to me was, you know: Everything in my closet is dead to me. I’ve been photographed, and the photographs are up on Facebook, and I need something new.

And, you know, Becky was a 25-year-old, like, normal girl who lived in New York. She wasn’t a celebrity, but she was talking about being photographed and not being able to wear something.

And it was like a light-bulb moment for me, because I realized I was having a conversation with my sister about the experience of wearing an amazing dress, of walking into a party, feeling self-confident and feeling beautiful. And that’s what she cared about. She didn’t care about the actual ownership of the items in her closet. The other thing she cared about was the photograph that would exist after the party that she could post on Facebook and kind of share with everyone.”

—Jenn Hyman, CEO and co-founder, via How I Built This

The RealReal

“The idea for The RealReal was born after I was out shopping with a girlfriend. My friend purchased items from a consignment rack in the back of an upscale boutique. I never knew her to shop consignment or buy from online resale websites. When I asked my friend why she said she trusted the shop owner—the shop was beautifully curated, and she was getting amazing deals on Chanel, Louis Vuitton, Gucci. It changed my perception of consignment.

The light bulb went off, and I did extensive research of the luxury and resale markets and even tested resale methods myself. […]

In December of 2011 I had my aha moment, and by early March, I picked out a name, registered the business, and raised capital. In June 2011 I opened the doors.”

—Julie Wainwright, CEO and co-founder, via Marin Magazine

Advice for finding startup ideas by following your curiosity:

Give yourself time to tinker: If you’re excited, make space in your life to explore the idea.

Build: Don’t just think. Build a prototype.

Keep it simple: Test the idea as cheaply as you can, as quickly as you can. Your first idea is unlikely to be exactly right.

Strategy 3: Pay attention to what’s already working, and double down (aka pivot)

The third most common path to a successful consumer business, a path just over 15% of the companies I looked at followed, is to first launch something, pay close attention to which elements (unexpectedly) work best, and then double down (aka pivot) to that one element. For example:

Instagram: Kevin Systrom noticed people weren’t using Burbn to check into places, but they were often sharing filtered photos they downloaded from other apps.

YouTube: The founders noticed their video-based dating site was more useful as a generalized platform for all types of videos.

Lyft: Logan Green and John Zimmer noticed their long-distance ridesharing service Zimride was struggling, but there was pent-up demand for shorter trips.

Pinterest: Ben Silbermann noticed that his e-commerce app Tote wasn’t taking off but that people loved saving collections of their favorite items.

Glossier: Emily Weiss noticed a budding need for personalized beauty products in her existing beauty community Into the Gloss.

PayPal: In one year, the founding team pivoted from encryption on mobile phones to cash on mobile phones to cash on PalmPilots to cash over email, based on their learnings about what was possible and useful.

Discord: Jason Citron found that his game business wasn’t working but that people loved its voice and text chat feature.

Twitch: Every other product the team tried faded, while this one side project continued to grow.

The best part about this strategy is that it should motivate you to launch whatever it is you’re currently most excited about—because even if the idea doesn’t work, it may lead you to the bigger idea.

“The stars will never align, and the traffic lights of life will never all be green at the same time. The universe doesn’t conspire against you, but it doesn’t go out of its way to line up the pins either. Conditions are never perfect. ‘Someday’ is a disease that will take your dreams to the grave with you. Pro and con lists are just as bad. If it’s important to you and you want to do it ‘eventually,’ just do it and correct course along the way.”

—Tim Ferriss

“If there were two paths where we had to choose one thing or the other, and one wasn’t obviously better than the other, then rather than spend a lot of time trying to figure out which one was slightly better, we would just pick one and do it. And sometimes we’d be wrong ... but oftentimes it’s better to just pick a path and do it rather than just vacillate endlessly on the choice.”

—Elon Musk, speaking about PayPal

Here are stories from companies that found their way to a massive business through pivoting, or simply doubling down on an idea that was already working:

Instagram

“Most people don’t realize that we were doing a completely different startup before we did Instagram. We were doing something called Burbn. I remember we had maybe 100 users using the service. It was a check‑in app, a lot like Foursquare meets Gowalla meets everything else. […]

We knew it wasn’t working when we would give it to people and they’d just keep bouncing off. The one thing that people would continue to do on the service was post square images from either Hipstamatic or CameraBag or whatever filter app existed out in the world, and people loved these posts.

They got the most likes. They got the most comments. I would ignore every other post on Burbn except for the photos.

One day, Mike, my co-founder, and I sat down, and we were like, ‘All right, we have to change something, because no one knows what we’re doing.’ We were like, ‘You know what? Let’s do what everyone’s doing on our service anyway. Let’s cut everything except for photos. Let’s build the filters in, and let’s allow for likes and comments and see what happens.’ I swear, the first day we launched it, we got 25,000 users.”

—Kevin Systrom, CEO and co-founder, via Startups.com

YouTube

“When YouTube first launched in May 2005, it was still intended to be a dating service, rather than a generalized platform for all types of videos. So in the early, early days, it was trying to see if there was a need for a video platform for dating (rather than just photos/messages).

I remember trying to recruit users to come to YouTube for that reason. We quickly realized that a dating platform wasn’t in demand of videos as the media type so we opened up the app to go after all types of content creators.”

—Steve Chen, co-founder

Lyft

“We were running Zimride, a long-distance ridesharing platform, and looking at the business, we realized that people took long trips pretty rarely. They also needed much more reliability than ‘I am heading to L.A. sometime this weekend,’ and coordinating pickup was a big challenge.

John Zimmer [co-founder] mocked up something called ‘On My Way’ during one of our hack days, which was a service that would notify your passengers as you were approaching them to pick them up for your Zimride. We also started thinking about creating an ‘instant ridesharing’ product with firm commitments, even dabbling with calling it ‘Zimride Instant’—but we weren’t sure it would be legal.

The Uber black-car experience was starting to take off, and then we saw Sidecar announce that they were going to launch that exact product we were thinking about. That was the kick in the rear we needed to hit the metaphorical gas. The founders grabbed a couple engineers and a designer, and three weeks—and a lot of hard work—later, that small team within Zimride launched Lyft.”

—Evan Goldin and Adam Fishman, early Lyft employees

Pinterest

“But while Tote users weren’t making purchases via the app, they were amassing growing collections of ‘favorite’ items to share with their friends. To Silbermann, who had collected insects as a kid, this was yet another example of people’s tendency to share their collections with one another. And while there was already a plethora of sites that allowed people to display virtual collections, they were all limited to a single item.

So a year after launching Tote, Silbermann pivoted to offer people a visually appealing way to display all their collections—whether they were books, adorable dog images, or women’s clothes—on the same site. […] Six months after its launch, Pinterest, then still an invitation-only site, had 80,000 collections.”

PayPal

“Of course, neither team had set out to build the world’s foremost email payments system. For X.com, like Confinity, the feature emerged as an afterthought.

In the fall of 1999, Musk and another X.com engineer discussed the concept of emailing money from one user to another, and they determined that an email address could function as a unique identifier, not unlike the digits of a checking account number. Nick Carroll, the engineer, recalled that the program took only a few days to build, ‘if even that.’

Musk concurred: ‘It’s trivial to do money transfer. It’s literally, you have a SQL database with one number, decrement that, and move it to another row in the database. It’s super dumb. My kid made one. He’s twelve.’

Carroll and Musk alike found the feature’s success surprising. ‘It was totally an add-on,’ Carroll admitted. Amy Rowe Klement recalled that the X.com team thought of the person-to-person payment product as simply its ‘user acquisition engine ... it wasn't the core business. That was the online financial superstore.’

Indeed, Musk was frustrated that X.com’s other products didn’t generate the same excitement. ‘We would show people the hard part—the agglomeration of financial

services—and nobody was interested. Then we’d show people the email payments—which was the easy part, and everybody was interested,’ Musk explained in a

2012 commencement speech at Caltech. ‘So I think it’s important to take feedback from your environment. You want to be as closed-loop as possible.’Despite frustration, the team responded to the product's strong market feedback and shifted focus to the incipient email product.”

—Jimmy Soni, The Founders: The Story of PayPal and the Entrepreneurs Who Shaped Silicon Valley

Glossier

“I started ‘Into the Gloss’ [a community she formed] because I wanted to create a space where people could celebrate beauty and share their routines. The women I was interviewing and the community that formed around the site had so much to say about their own experiences, and it struck me that brands were failing to leverage the power of their own customers. There had always been a ‘brand knows best’ approach—here’s an issue and a product to fix it. It really was an aha moment when I decided that, with our community, we could create a modern beauty experience that empowered people to be their own experts.”

—Emily Weiss, CEO and founder, via Irish Tatler

Discord

“His first company started as a video game studio and even launched a game on the iPhone App Store’s first day in 2008. That petered out and eventually pivoted into a social network for gamers called OpenFeint, which Citron described as ‘essentially like Xbox Live for iPhones.’ He sold that to the Japanese gaming giant Gree, then started another company, Hammer & Chisel, in 2012 ‘with the idea of building a new kind of gaming company, more around tablets and core multiplayer games.’ It built a game called Fates Forever, an online multiplayer game that feels a lot like League of Legends. It also built voice and text chat into the game, so players could talk to each other while they played.

And then that extremely Silicon Valley thing happened: Citron and his team realized that the best thing about their game was the chat feature. This was circa 2014, when everyone was still using TeamSpeak or Skype and everyone still hated TeamSpeak or Skype. Citron and the Hammer & Chisel team knew they could do better and decided they wanted to try.

It was a painful transition. Hammer & Chisel shut down its game development team, laid off a third of the company, shifted a lot of people to new roles, and spent about six months reorienting the company and its culture. It wasn’t obvious its new idea was going to work, either. ‘When we decided to go all in on Discord, we had maybe 10 users,’ Citron said. There was one group playing League of Legends, one WoW guild, and not much else. ‘We would show it to our friends, and they’d be like, ‘This is cool!’ and then they’d never use it.’

After talking to users and seeing the data, the team realized its problem: Discord was better than Skype, certainly, but it still wasn’t very good. Calls would fail; quality would waver. Why would people drop a tool they hated for another tool they’d learn to hate? The Discord team ended up completely rebuilding its voice technology three times in the first few months of the app’s life. Around the same time, it also launched a feature that let users moderate, ban, and give roles and permissions to others in their server. That was when people who tested Discord started to immediately notice it was better. And tell their friends about it.”

Twitch

“It was as classmates at Yale University that the two [Emmett Shear and Justin Kan] first worked together, launching a web calendar startup called Kiko in 2005. It didn’t last. One month after launch, Kiko—designed to combine the power of Microsoft Outlook with the modern web sensibilities of Google’s then-new email product Gmail—was buried by a different solution: Google Calendar. After 14 months, Kiko did find an exit, however … it was sold on eBay, for $258,000.

That money kept them going, and they learned from a series of further fizzle-outs, like a Facebook-for-families social network and a company that would sell glow-in-the-dark gene-spliced roses. Then the duo landed on one idea that Y Combinator founder Paul Graham was willing to invest $50,000 to see: a reality show devoted to broadcasting Kan’s life on the web, 24/7.

Justin.tv began broadcasting in early 2007 and quickly scored some major headlines; Kan even wound up on NBC’s Today show and ABC’s Nightline. Shear said that part of what made the Truman Show-esque experiment work was that this time, the product was something its creators wanted for themselves.

The site opened up to other broadcasters in October 2007. Three years later, Justin.tv had raised $7.2 million in venture capital and was claiming some 31 million unique users per month.

It was at this time, in late 2010, that the company began working on two ‘skunkworks’ projects. One project, a Justin.tv mobile initiative led by Michael Seibel, would spin off into an Instagram-for-video startup called Socialcam, which sold to Autodesk for $60 million in 2012. The other, a task force led by Shear to grow the audience for video game content on the site, would also become its own product: a new site called TwitchTV.

TwitchTV (later shortened to Twitch) has outpaced its predecessor. Meanwhile, Justin.tv’s star has faded.”

Advice for finding startup ideas by doubling down:

Kill your darlings: You may love your idea, but if not enough other people do, it won’t work.

Don’t take what’s working for granted: If any part of your product is proving to be valuable to people, that’s a rare find. Embrace it.

Try stuff: The more ideas you put out there, the more likely you are to find something that sticks.

Strategy 4: Pay attention to paradigm shifts, and work backward

Another common strategy to coming up with an idea is to simply notice a shift in where the world is going, and work backward. As Mike Maples Jr. put it, “Start from the future and work backwards,” and as Paul Graham said, “Live in the future, then build what’s missing.”

“From mobile to social to crypto, there’s so many examples where people failed to imagine what a couple years of compounding developments would look like, in terms of technology speed improving, costs dropping, or adoption increasing. We should be monitoring what’s compounding at a fast rate or, alternatively, where adoption is growing reasonably rapidly. The proof is in the growth rate or the extrapolated technology curve rather than the number sitting in front of you in that moment.”

—Elad Gil, founder and investor

Examples of founders doing just that:

Spotify: Daniel Ek realized that the future of music was paid.

Amazon: Jeff Bezos noticed that the web was growing 2,300% a year and found a product that would most benefit from being sold online: books.

23andme: Anne Wojcicki realized that genetic information was suddenly cheap and available.

Instacart: Max Mullen and Apoorva Mehta noticed the rise of on-demand ridesharing and delivery services.

Stitch Fix: Katrina Lake noticed that retail was going to move online.

Here are their stories:

Spotify

“I realized that you can never legislate away from piracy. The only way to solve the problem was to create a service that was better than piracy and at the same time compensates the music industry. That gave us Spotify.”

—Daniel Ek, CEO and founder, via Fast Company

Amazon

“I was in New York City working for a quantitative hedge fund when I came across the startling statistic that web usage was growing at 2,300% a year. So I decided I would try and find a business plan that made sense in the context of that growth, and I picked books as the first best product.

I made a list of like 20 different products that you might be able to sell, and books were great as the first product because books are incredibly unusual in one respect—that is that there are more items in the book category than there are items in any other category by far. Music is number two. There are about 200,000 active music CDs at any given time, but in the book space, they are more than 3 million different books worldwide, active, and printed at any given time.”

—Jeff Bezos, founder and CEO, via YouTube

23andme

“I happened to be—when I was investing on Wall Street—I happened to realize genetic information, it was suddenly cheap to get access to a broad amount of information on your genome. And I was really lucky noticing that, one, suddenly, individuals could get access to your genome. And then there was this whole convergence of Web 2.0. There was going to be social networks. And you’re going to find each other. And it was hot. It was so interesting.

And I suddenly realized that one of the things that’s a big issue in health care is there’s a lack of data. So routinely, my sister, who does nutrition research, said: you look at those studies, and it’s like 200 patients here, 200 there. And my dad, who is a particle physicist, would be like: anyone who knows about statistics knows you can’t find anything in this. You need lots of data. And clearly, the Google world had taught me the value of lots of data and what you can do with it.

So I got lucky with this idea of, why do I need Stanford? Why do I need Pfizer to go and do all this research? I can just allow all these people to learn about their genome. It’s so cool. Learn about your genetics. And then we’re going to bring everyone together in this whole new research model. It’s going to be like crowdsourcing. We’re going to have the world’s data. I don’t need Stanford and Pfizer and all these other people. I don’t want you to be a human subject. I want it to be a live participant, excited in research. So we had this idea of really marrying this idea of cool technology with this concept of Web 2.0. And we launched the company.”

—Anne Wojcicki, CEO and co-founder, via Talks at Google

Instacart

“I had several life experiences over the 10 years leading up to starting the company that eventually gave me the insight that this would become a huge consumer need. They included early adopting Web 1.0 delivery services, a business plan I wrote in college for a food marketplace, and then seeing the early days of ridesharing in 2011 after moving to San Francisco.

Once I had that insight in April 2012, I was on a warpath to start this company, and I started telling my smartest friends about the idea and getting their feedback. By luck, one of them was Brandon, who introduced me to Apoorva in June 2012, and he had a similar consumer insight from working at Amazon. Then Apoorva and I brought Brandon on as our third co-founder in July 2012, and the rest is history.”

—Max Mullen, co-founder

Stitch Fix

“I moved on from Parthenon to become an associate at Leader Ventures, a VC firm, just as the iPhone appeared, in 2007. I was thinking about retail. I studied the economics of Blockbuster during the rise of Netflix. On one side was a company that dominated physical store sales; on the other was a company that dominated sales without stores. It was the perfect case study. And I could see exactly when the scale tipped. Whenever Netflix hit about 30% market share, the local Blockbuster closed. The remaining 70% of customers then faced a decision: try Netflix or travel farther to get movies. More of them tried Netflix, putting more pressure on Blockbuster. Another store would close, and more customers would face that try-or-travel decision, in a downward spiral.

I recognized that other retailers might suffer Blockbuster’s fate if they didn’t rethink their strategy. For example, how would someone buy jeans 10 years down the road? I knew it wouldn’t be the traditional model: go to six stores, pull pairs of jeans off the racks, try them all on. And I didn’t think it would resemble today’s e-commerce model either: You have 15 tabs open on your browser while you check product measurements and look for what other shoppers are saying. Then you buy multiple pairs and return the ones that don’t fit.

The part of me that loves data knew it could be used to create a better experience with apparel.”

—Katrina Lake, founder, via Harvard Business Review

Advice for finding startup ideas by looking into the future:

Spend time thinking: What is likely to be very different in 5, 10, 20 years?

What hasn’t software eaten? Find a big market with a bad customer experience.

What would be amazing if it were possible? Start with the ideal experience, and figure out what it would take to make it possible.

Strategy 5: Brainstorm with friends, and pay attention to the four points above

A final strategy is to simply sit around with your friends and think up ideas. Eight out of the 50 companies I looked at found their idea through active brainstorming. Michael Seibel has some great advice on this path (30-second clip):

Here are a number of examples of this working:

Thumbtack

“The conventional wisdom when starting a company is to work on a problem that you’ve faced personally.

At Thumbtack, we didn’t do that. Instead, for a year we brainstormed on weekly phone calls ideas of things we could start that, if successful, would create opportunity for people. We were focused on impact at scale. We knew we weren’t representative of the general population. We focused on issues that most people faced even if we didn’t personally.We threw so many ideas at the wall over the course of a year. The first one that stuck was an aggregator for all of one’s online financial accounts. We drafted our business plan ... then a couple weeks later, Mint.com launched and won TechCrunch 50. So we then moved to the second (and better!) idea that stuck—for Thumbtack. I don’t recall the specific moment the idea for Thumbtack came up. These ideas all came from observing the problems people faced in the world and thinking about how we could use technology to make things a bit better.”

—Sander Daniels, co-founder

Netflix

“Silicon Valley loves a good origin story. The idea that changed everything, the middle-of-the-night lightbulb moment, the what if we could do this differently? conversation. Origin stories often hinge on epiphanies. The stories told to skeptical investors, wary board members, inquisitive reporters, and—eventually—the public usually highlight a specific moment: the moment it all became clear. […]

There’s a popular story about Netflix that says the idea came to Reed after he’d rung up a $40 late fee on Apollo 13 at Blockbuster. He thought, What if there were no late fees? And BOOM! The idea for Netflix was born. That story is beautiful. It’s useful. It is, as we say in marketing, emotionally true. But as you’ll see in this book, it’s not the whole story. Yes, there was an overdue copy of Apollo 13 involved, but the idea for Netflix had nothing to do with late fees—in fact, at the beginning, we even charged them. More importantly, the idea for Netflix didn’t appear in a moment of divine inspiration—it didn’t come to us in a flash, perfect and useful and obviously right.

The truth is that for every good idea, there are a thousand bad ones. And sometimes it can be hard to tell the difference.

Customized sporting goods. Personalized surfboards. Dog food individually formulated for your dog. These were all ideas I pitched to Reed. Ideas I spent hours working on. Ideas I thought were better than the idea that eventually— after months of research, hundreds of hours of discussion, and marathon meetings in a family restaurant—became Netflix.

I had no idea what would work and what wouldn’t. In 1997, all I knew was that I wanted to start my own company, and that I wanted it to involve selling things on the internet. That was it.”

—Marc Randolph, CEO and co-founder, author of That Will Never Work

Yelp

“So I got to Max [Levchin]’s little office, little dumpy office, brick lined room, and it was just a bunch of different folks working on little internet ideas. What’s going to be the next big thing on the internet—which I actually was intrigued by. And I thought, well, this is a fun exercise. I’ve always wanted to start a company—this is a good trial run for me to see if I could come up with a compelling idea that I could pitch Max on that he would actually get excited about. […]

There was some interest within the incubator around the local space. It was, you know, we were observing. Craigslist was killing the newspaper business by carving out classifieds, and so that put a spotlight on the Yellow Pages, like, hey, here’s another old media business that hasn’t really been transformed by the internet.

And so that got us thinking about what would be, you know, better than the Yellow Pages. And as I thought about and talked about it with my co-founder, Russ Simmons, who was another early PayPal person, you know, reviews, capturing word of mouth, bringing it online, marrying it with social networking—which was another technology that was just emerging; you had Friendster and MySpace. It seemed intriguing, but we didn’t think you could create a social network just around reviewing.

It took us a couple of months, maybe a month and a half or so, to really zero in on an idea. Eventually I said to [Russ], you know, what if you asked me a question, like who’s a good doctor in San Francisco—I love to be the expert, I love to reply, to give you this helpful information. So out of this sort of back-and-forth conversation about questions, the idea emerged: maybe we can build a site around asking friends for recommendations.”

—Jeremy Stoppelman, CEO and co-founder, via How I Built This

Reddit

“Somewhere in the middle of Connecticut, on an exceptionally long train ride back to Virginia, my cell phone rang. It was Paul Graham. He wanted us back, but only if we changed our idea to something else. So much for proving them wrong. We got off at the very next stop, but not before I got Paul to buy us a pair of tickets to fly back to Charlottesville that night so we could return to Boston for an hour to join him in ‘brainstorming a better idea than mobile food ordering.’ […]

We got back to the Y Combinator office and met with Paul Graham alone, without his partners. He told us to forget mobile for a moment and consider building something for the browser. […]

He asked us about frustrations we had using the internet, which had just recently seen the launch of a college-only site called TheFacebook.com. Steve was an avid reader of Slashdot, a news website with editorial oversight and a robust community of commenters as well as a moderation system. I had too many tabs open every day—they showed me a range of news websites, but I had no way to filter signal from noise.

At the time, a website called del.icio.us (pronounced ‘delicious’; ignore the dots) let people bookmark websites online, so if you hopped between computers, your reference material followed you. An interesting by-product of this was del.icio.us/popular, which aggregated the most popular bookmarked URLs at any given time. There was something here that del.icio.us wasn’t quite getting, but we saw the potential for something bigger, which would sort not the most popular links for bookmarking but the most popular links for sharing.

We hadn’t figured out functionality, but we knew the old model for news aggregation, when it was printed on a dead tree, wasn’t suited for the internet age. In fact, the vision was best crystallized by Paul Graham in that very meeting: ‘That’s it! You should build the front page of the web.’ ”

—Alexis Ohanian, CEO and co-founder, via Reddit

Nextdoor

“We had no hierarchy at all. And we had this standing 10 a.m. meeting to come up with billion-dollar ideas. It was fun. We were kind of poking fun at it.

And you would have ideas and they would come up and people would talk about them and then you’d find out, ‘Okay, who wants to go work on that?’

We had a lot of ideas that were focused on building and taking advantage of online community because that’s what we understood and what we knew. One of those ideas was what became Nextdoor, where one of our co-founders came in and said, ‘Hey, I’m trying to get a pothole fixed in my neighborhood and I realized there’s no way to communicate with the folks who live around me.’

I remember the moment he said it. ‘Oh, that’s super interesting.’ And then we started to ... like, well, you have Facebook for friends and family, people you know. LinkedIn for your professional contacts. But people who live around you, how do you have a way to communicate with them?”

—Sarah Leary, CEO and co-founder, via Mike Maples, Jr.

DoorDash

“During our second year in b-school, we wanted to build something. We went door to door and asked business owners to tell us about their work. The most useful question, for me, was ‘Tell me everything you’ve done since getting here today.’

Delivery first came up at a macaron shop. We were wrapping up an interview when we overheard the manager turn down a delivery order. If there was a light-bulb moment, this was it—why couldn’t businesses send things across town, on demand? There should be an on-demand FedEx!

We tested just the consumer part first. We made a static HTML page at http://paloaltodelivery.com with a Google Voice number and a few PDF menus from local restaurants, offering delivery for $6. We launched a small AdWords campaign to see if anyone was searching for it.

Hours later, Tony [Xu] and I were driving home when we got the first order. I grabbed a notebook and wrote down what the guy wanted from a local Thai restaurant. We placed a takeout order, drove to the restaurant, bought the food, took it to the customer, and charged him with Square.

We quickly had trouble keeping up. I remember running out of class to answer the phone more than a few times. We probably took ‘Do things that don’t scale’ too far.”

—Evan Moore, co-founder, via Twitter

Bumble

“I received an email from Andrey Andreev—we’d met back in 2013, and he’d always said he wanted to speak to me when I had my next step after Tinder. We got speaking—he was really convincing—and said, ‘Hey! You should come be the CMO for my dating app.’ At the time I was allergic to dating apps and didn’t ever want to be in the space again. I told him, ‘Thank you so much; it’s really kind of you to have that belief in me. I’d love to work with you, but I want to start my own company and be CEO. I’m thinking of starting a social network, where the currency is compliments, just for girls and women…’

I’d had a really tumultuous summer where I was being abused on the internet by strangers, and I really wanted to clean up the internet for young girls. I shared this vision with Andrey and he said, ‘That’s a great vision; I believe in it. I see these issues all the time on the internet, and there’s definitely something here. Why don’t we turn the concept into a dating app?’ I thought he was mad. I thought he’d lost his mind, but you know what? He was absolutely right—there was a huge opportunity to improve the dating space for women.

We sat down, brainstormed what a dating app for women would look like—how it would work, how our past experiences could be drawn on—and it came down to one thing. Women were never in the driver’s seat with dating. It always came down to the man to take the lead, to ask the girl. There was this playbook where the guy has the power, the girl is weak and fragile waiting to be saved by Prince Charming—and this is disempowering for both sides.

We decided to flip the script and empower people through connections, reducing rejections on the man’s side and empowering women to make the first move and be confident. That was the beginning of Bumble. And here we are, five years later, with almost 60 million users globally.”

—Whitney Wolfe Herd, CEO and co-founder, via ThoughtEconomics

Eventbrite

“[Kevin Hartz] was already transitioning out of Xoom and he was starting to look at what he wanted to do next, what he wanted to build next. So he was primed to be in ideation phase.

There were several ideas that he had actually prototyped and, to some extent, had built early versions of. One of the things was about this very simple transactional platform to sell tickets to any kind of event. […] And that became, that was the first idea that we had to work on together and, you know, just so happened to stick.”

—Julia Hartz, CEO and co-founder, via How I Built This

Should you sit around and think, or wait for an idea to strike?

Of the more than 50 companies I looked at, fewer than 10 founders had sat around and actively brainstormed startup ideas. I’m sure many other founders were thinking about startup ideas passively, but most didn’t actively try to think of one. The majority of ideas emerged organically, out of the founders’ attempt to solve their own problem, following their innate curiosity, trying something and then doubling down on the part that was working, or having a sudden insight into a much better user experience.

This isn’t to say that you shouldn’t spend time ideating—it just means that isn’t where most of the biggest consumer startup ideas have come from.

What makes a good idea?

Although there’s no way to truly know if your idea will work (otherwise, some VC would be batting a thousand) and many really good ideas fail, based on my research, the more of the following elements your idea has, the more likely it is to succeed:

1. You can’t stop thinking about the idea

Startups only really fail when the founder gives up. The more passionate you are about your idea, the less likely you are to do that.

Max Mullen, Instacart: “I was on a warpath to start this company.”

Neil Blumenthal, Warby Parker: “You know one of those moments when you can’t sleep because you are just thinking? […] The four of us each had that feeling in our stomachs where we thought that we were really onto something and we really couldn’t sleep, and it was that next day that we all met back up at school and were committed to doing whatever it took to make it happen.”

Brian Armstrong, Coinbase: “It was kind of an obsession. I don’t know what you’d call it. I kind of couldn’t help myself. I remember I was actually almost trying to talk myself out of it at a certain point because I was like: if you’d go down this rabbit hole, you know, you’re not going to be able to get out of it because this is not some kind of throwaway project you can do.”

“We hear again and again from founders that they wish they had waited to start a startup until they came up with an idea they really loved.”

—Sam Altman

2. You immediately start building a prototype, and have the skills to do it

Most of the companies I researched emerged out of a scrappy experiment that came together hours/days/weeks after the founders had the idea. That isn’t always the case, but it seems to be common for successful consumer companies. This is likely why over 80% of the startups had an engineering co-founder.

Twitter: “We went off and built a prototype in two weeks.”

Tinder: “Over the course of the hackathon, they built the first prototype.”

Lyft: “The founders grabbed a couple engineers and a designer, and three weeks—and a lot of hard work—later, that small team launched Lyft.”

Patreon: “The very day [I] had the meeting to talk about the idea, I went home to work on the code. I started working probably more passionately than ever on any other project. For me it felt like a race, and I had this fear that if we didn’t move fast on this, someone else would do it and I’d regret that.”

3. You have unique insight into the opportunity

Although only about half of the startups I looked at were started by founders with specialized skills/experience, the majority of founders had a unique insight into the opportunity, based on some prior experience they had.

For example, Alex Zhu worked on video and music apps before TikTok, Larry and Sergei wrote research papers and saw how citations were a sign of content value, and Brian Armstrong had a dual bachelor’s degree in economics and computer science. The unique insight is also why some of the best ideas initially sound crazy (e.g. Airbnb, Uber), trivial (e.g. Cameo, DoorDash), or impossible (e.g. Uber, Spotify, DoorDash)—you see the world differently from those around you.

For that reason, also notice that among the stories I shared, rarely is user research a big factor in the early ideating. Most ideas emerged out of the founders’ experience, vision, and gut instincts.

4. The idea is easy to understand

Every product we’ve looked at can be explained in a sentence or two. We’ll spend more time on this in Part 3 of this series.

Broadly, if you can combine the right founder—who can’t stop thinking about that idea, has a unique insight into the opportunity and the right skills, with market timing—you create the opportunity for massive consumer businesses.

This is also why you shouldn’t be super-worried about someone stealing your idea—the chances that anyone else has this rare combination at the right time are incredibly low.

What to do once you have an idea

As Walt Disney said, “The way to get started is to quit talking and begin doing.” Here’s my advice on what to do as soon as you have an idea you’re excited about.

1. Prototype it cheaply and quickly to validate the idea

Stitch Fix: “Lake used SurveyMonkey to track customers’ preferences and then toted armloads of garments to their homes, accepting checks to cover the $20 styling fee.”

Netflix: “We turned the car around mid-commute and drove back down to the town we lived and tried to buy a DVD. And of course there weren’t any—it was in test market—so we bought a used music CD and mailed that to Reed’s house in Santa Cruz for the price of a postage stamp. And the next morning, we learned is it a good idea or a bad idea.”

DoorDash: “We tested just the consumer part first. We made a static HTML page at http://paloaltodelivery.com with a Google Voice number and a few PDF menus from local restaurants, offering delivery for $6. We launched a small AdWords campaign to see if anyone was searching for it. Hours later, Tony and I were driving home when we got the first order.”

Rec Room: “They built the first game within 90 days and launched it quietly on SteamVR.”

Hipcamp: “I learned how to program later that year. That June, I launched a very, very beta version of the website.”

Don’t miss Todd Jackson’s in-depth post on validating your idea.

2. Talk to potential customers to refine your idea

Rent The Runway: “‘You know, we should really call Diane von Furstenberg,’ Jenny said. ‘Do you know Diane von Furstenberg?’ And I said, ‘Obviously I don’t know Diane von Furstenberg. But we could probably figure out her email address.’ Jenny and I wrote an email that afternoon to many different versions of Diane von Furstenberg’s email address. And we basically said, ‘Hey, we’re two women at Harvard Business School. We’d love to come in and talk to you about it.’ And this is where luck plays into the situation, because she or someone from her office opened that email. She responded, ‘I’ll see you tomorrow at 5 p.m.’ And we drove down to New York that next day, put on our DVF dresses, and walked into her office and introduced ourselves.”

Rec Room: “To get early testers, they set up in the lobby of their WeWork and asked people walking by to check out the app.”

Discord: “Citron and Stan immediately jumped into the server, hopped into voice chat, and started talking to anyone who showed up.”

3. Figure out who you are building for

… and this is exactly what we’re going to be focusing on in our very next post!

Next week: 🕵️ Identifying your super-specific who

Two final words of wisdom:

“Don’t worry about failure. You only have to be right once.”

—Drew Houston

“The critical ingredient is getting off your butt and doing something. It’s as simple as that. A lot of people have ideas, but there are few who decide to do something about them now. Not tomorrow. Not next week. But today. The true entrepreneur is a doer, not a dreamer.”

—Nolan Bushnell

A big thank-you to Alyssa Ravasio (Hipcamp), Chris Best and Hamish McKenzie (Substack), Devon Townsend (Cameo), Evan Goldin and Adam Fishman (Lyft), Julia Hartz (Eventbrite), Max Mullen (Instacart), Sander Daniels (Thumbtack), and Steve Chen (YouTube) for generously sharing their stories for part one of this series.

📚 Further study

How to get startup ideas by Paul Graham

How to get and test startup ideas by Michael Seibel

How to validate your startup idea by Todd Jackson

How to start a startup by Sam Altman and Dustin Moskovitz

How to build a breakthrough by Mike Maples, Jr.

12 frameworks for finding startup ideas by First Round Capital

Finding the right idea by Pioneer

The hidden backstory of 5 startup pivots that grew to $43B by Jason Shen

Have a fulfilling and productive week 🙏

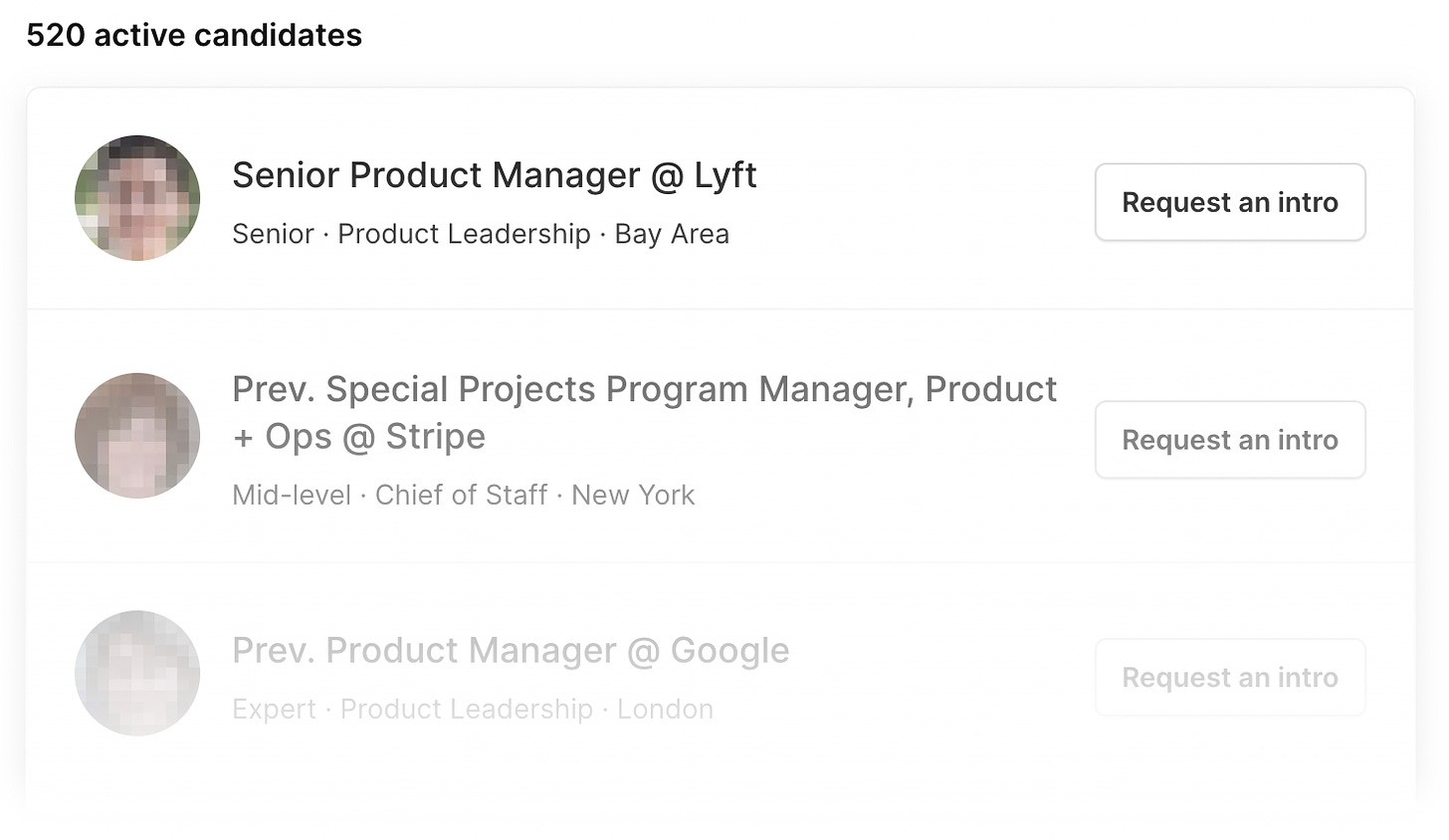

📣 Join Lenny’s Talent Collective 📣

If you’re hiring, join Lenny’s Talent Collective to start getting bi-monthly drops of world-class hand-curated product and growth people who are open to new opportunities.

If you’re looking for a new gig, join to get personalized opportunities from hand-selected companies. You can join publicly or anonymously, and leave anytime.

🔥 Featured job openings

Fountain: Senior Product Manager (Remote)

Render: Product Manager (Remote)

Mine’d: Head of Product (N.Y., Remote)

OpenStore: Product Marketing Manager (Miami)

Ashby: First Lead UX Designer (L.A., S.F., Vancouver, Austin, Tribeca)

Wethos: Director, Growth Product Marketing (Remote)

Scratchpad: Senior Product Manager (Remote)

Joby Aviation: Air Taxi Product Manager-Operations (San Carlos, CA)

Finding this newsletter valuable? Consider sharing it with friends, or subscribing if you haven’t already.

Sincerely,

Lenny 👋

So much value in this one! Definitely bookmarking to revisit later as well.

Paying attention to my own problems and solving it is something that I'm focusing on right now. Will fine tune my thought process with additional insights in this piece!

I have never seen such valuable content anywhere else.

The best idea is to solve your own problems and then offer that solution to others. Thanks for the details!