Why your AI product needs a different development lifecycle

Introducing the Continuous Calibration/Continuous Development (CC/CD) framework

👋 Welcome to a ✨ free edition ✨ of my weekly newsletter. Each week I tackle reader questions about building product, driving growth, and accelerating your career. For more: Lenny’s Podcast | How I AI | Lennybot | Lenny’s Reads | Courses

P.S. Annual subscribers get a free year of 15+ premium products: Lovable, Replit, Bolt, n8n, Wispr Flow, Descript, Linear, Gamma, Superhuman, Warp, Granola, Perplexity, Raycast, Magic Patterns, Mobbin, and ChatPRD (while supplies last). Subscribe now.

In this AI era, tech leaders need to re-evaluate every single industry best practice for building great products. AI products are just built differently. The teams that realize that and adjust the most quickly will have a huge advantage.

Based on their experience leading over 50 AI implementations at companies including OpenAI, Google, Amazon, Databricks, and Kumo, Aishwarya Reganti and Kiriti Badam have developed the Continuous Calibration/Continuous Development (CC/CD) framework to specifically address the unique challenges of shipping great AI-powered products. In this post, they’re sharing it for the first time with you.

For more from Aish and Kiriti, check out their popular Maven course and their upcoming free lightning talk that explores this topic in depth.

You can also listen to this post in convenient podcast form: Spotify / Apple / YouTube

If you’re a product manager or builder shipping AI features or products, you’ve probably felt this:

Your company is under pressure to launch something with AI. A promising idea takes shape. The team nails the demo, the early reviews look good, and stakeholders are excited. You push hard to ship it to production.

Then things start to break. You’re deep in the weeds, trying to figure out what went wrong. But the issues are tangled and hard to trace, and nothing points to a single fix. Suddenly your entire product approach feels shaky.

We’ve seen this play out again and again. Over the past few years, we’ve helped over 50 companies design, ship, and scale AI-powered autonomous systems with thousands of customers. Across all of these experiences, we’ve seen a common pitfall: people overlook the fact that AI systems fundamentally break the assumptions of traditional software products.

You can’t build AI products like other products, for two reasons:

AI products are inherently non-deterministic

Every AI product must negotiate a tradeoff between agency and control

When companies don’t recognize these differences, their AI products face ripple effects like unexpected failures and poor decision-making. We’ve seen so many teams experience the painful shift from an impressive demo to a system that can’t scale or sustain. And along the way, user trust in the product quietly erodes.

After seeing this pattern play out many times, we developed a new framework for the AI product development lifecycle, based on what we’ve seen in successful deployments. It’s designed to recognize the uniqueness of AI systems and help you build more intentional, stable, and trustworthy products. By the end of this post, you should be able to map your own product to this framework and have a better sense of how to start, where to focus, and how to scale safely.

Let’s walk through the ways that building AI products is different from traditional software.

1. AI products are inherently non-deterministic

Traditional software behaves more or less predictably. Users interact in known ways: clicking buttons, submitting forms, triggering API calls. You write logic that maps those inputs to outcomes. If something breaks, it’s usually a code issue, and you can trace it back.

AI systems behave differently. They introduce non-determinism on both ends: in other words, there’s unpredictability in how users engage and how the system responds.

First, the user interaction surface is far less deterministic. Instead of structured triggers like button clicks, users interact through open-ended prompts, voice commands, or other natural inputs. These are harder to validate, easier to misinterpret, and vary widely in how users express intent.

Second, the system’s behavior is inherently non-deterministic. AI models are trained to generate plausible responses based on patterns, not to follow fixed rules. The same request can produce different results depending on phrasing, context, or even a different model.

This fundamentally changes how you build and ship. You’re no longer designing for a predictable user flow. You’re designing for likely behavior—both from the user and the product—not guaranteed behavior. Your development process needs to account for that uncertainty from the start, continuously calibrating between what you expect and what shows up in the real world.

2. Every AI product negotiates a tradeoff between agency and control

There’s another layer that makes AI systems different, and it’s one we rarely had to think about before with traditional software products: agency.

Agency, in this context, is the AI system’s ability to take actions, make decisions, or carry out tasks on behalf of the user (which is where the term “AI agent” comes from). Think:

Booking a flight

Executing code

Handling a support ticket from start to finish

Unlike traditional tools, AI systems are built to act with varying levels of autonomy. But here’s the part people often overlook:

Every time you give an AI system more agency, you give up some control.

So there’s always an agency-control tradeoff at play. And that tradeoff matters (a lot!). If your system suggests a response, you can still override it. If it sends the response automatically, you’d better be sure it’s right.

The mistake most teams make is jumping to full agency before they’ve tested what happens when the system gets it wrong. If you haven’t tested how the system behaves under high control, you’re not ready to give it high agency. And if you hand over too much agency without the system earning it first, you may lose visibility into the system, and the trust of your users.

What’s more, you’re stuck debugging a large, complicated system that has taken actions you can’t trace, for reasons you’ve lost insight into, so you don’t even know what to change.

Which brings us to the core framework we’ve developed to help teams navigate these distinctions.

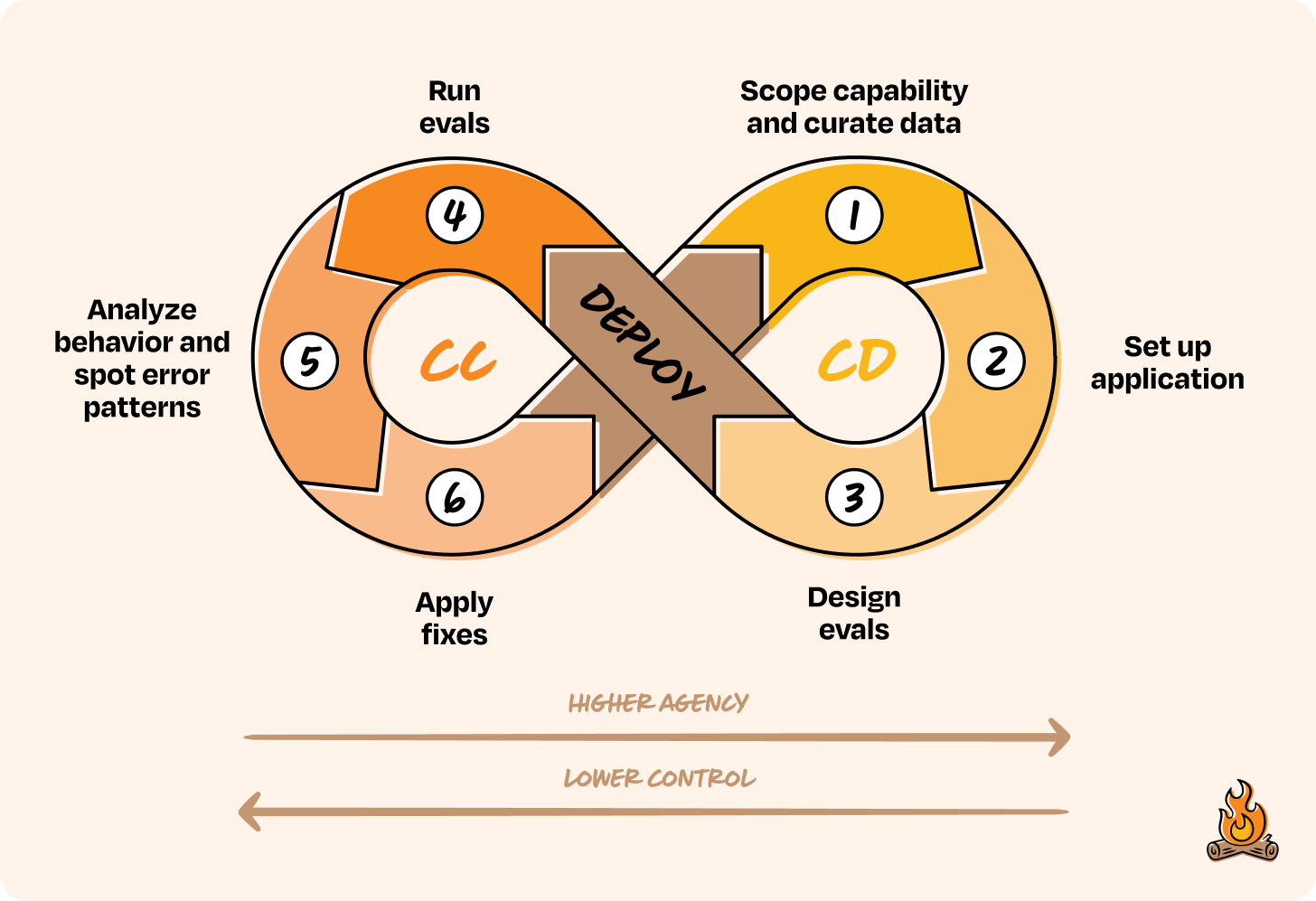

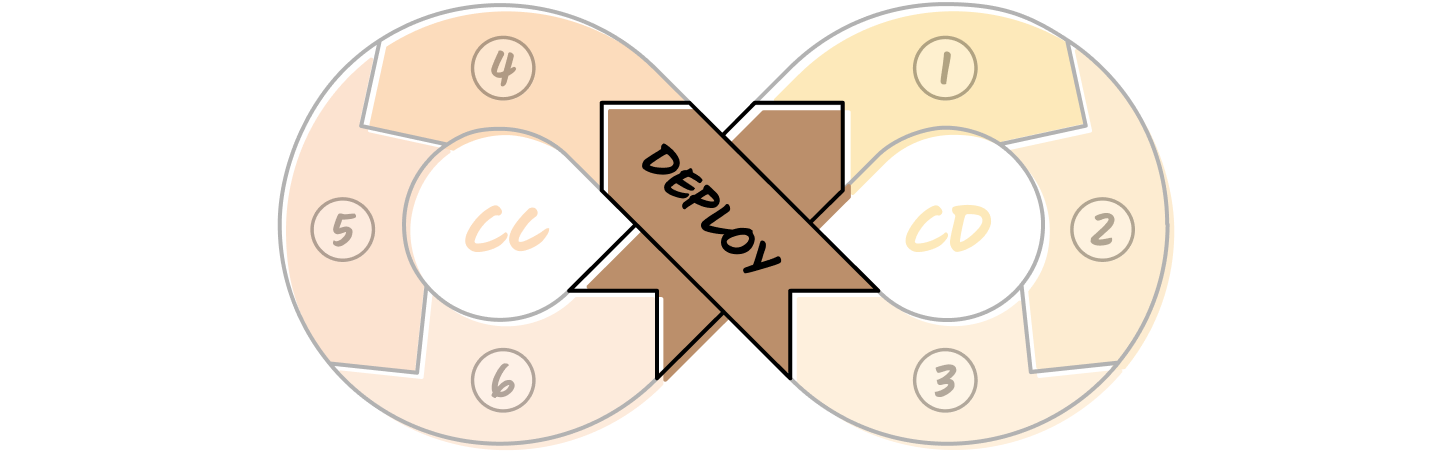

We call it CC/CD: Continuous Calibration/Continuous Development.

The name is a reference to Continuous Integration/Continuous Deployment (CI/CD), but, unlike its namesake, it’s meant for systems where behavior is non-deterministic and agency needs to be earned.

The Continuous Calibration/Continuous Development framework

Just like in traditional software, AI products move through phases toward an end goal. But building AI requires you to account for two things we mentioned earlier: non-determinism and the agency-control tradeoff.

The CC/CD framework is designed to work around these two realities by:

Reducing a system’s non-determinism through design or by monitoring it closely

Ensuring that agency is earned over time, not granted all at once, because every new capability shifts control further away from humans

In our framework, product builders work in a continuous loop of development (CD) and calibration (CC). During development, you scope the problem, design the architecture, and set up evaluations to keep non-determinism in check. You start with features that are low-agency and high-control, then gradually move up as the system proves it can handle more.

Then you deploy, not as a finish line but as a transition into the next phase. Once you’ve deployed, you enter the calibration loop, where you observe real behavior, figure out what broke, and make targeted improvements.

With every cycle, the system earns a bit more agency. Over time, this loop turns into a flywheel, tightening feedback, building trust, and making the product stronger with each version.

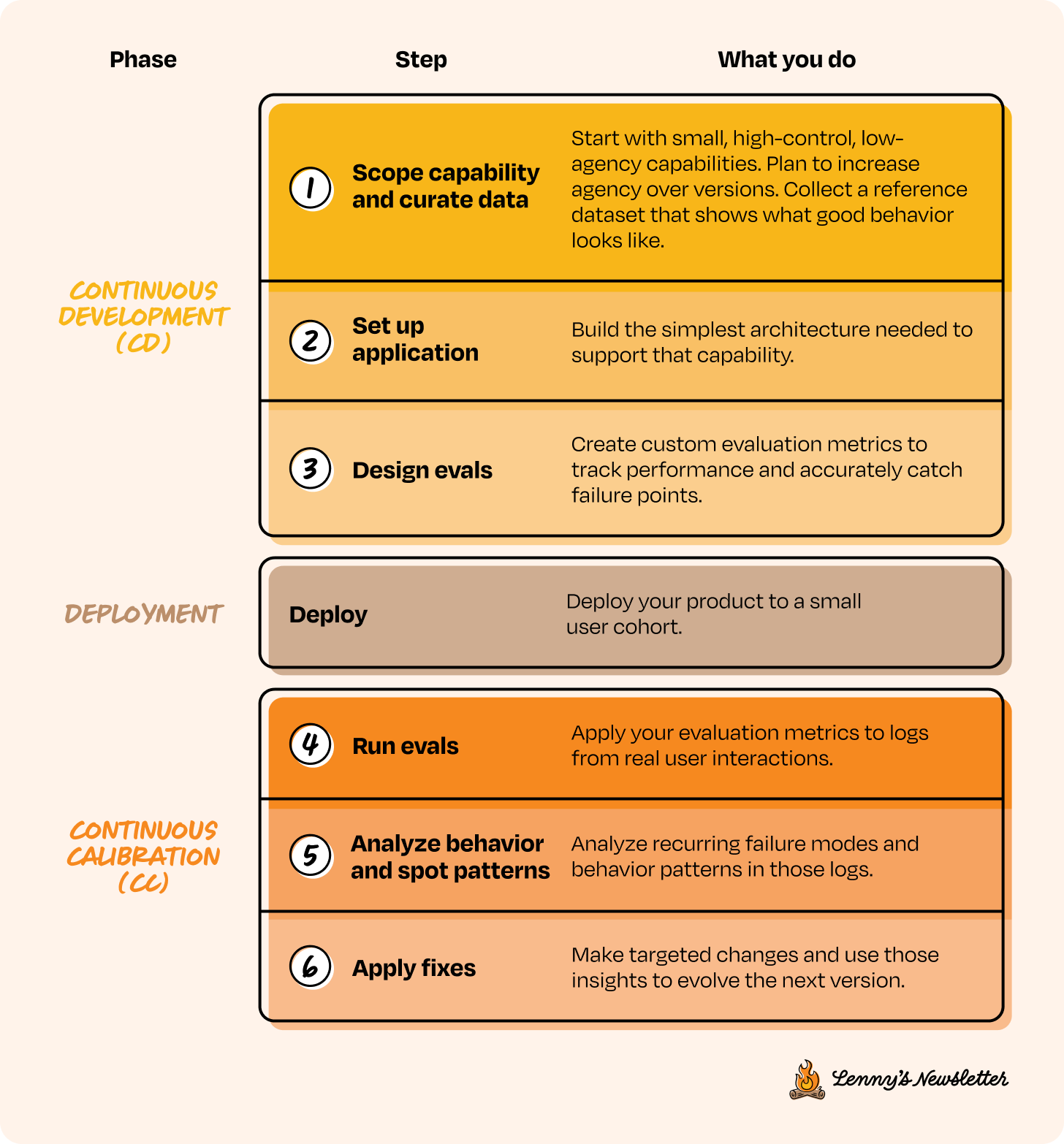

Let’s go deeper into each step of the CC/CD loop, what it looks like, why it matters, and how to do it well. The first three steps make up the Continuous Development side of the loop: scoping the capability, setting up the application, and designing evals.

CD 1. Scope capability and curate data

Let’s say you have a big product idea and you’ve already done your research. It’s clear that AI is the right approach. In traditional software development, you’d typically plan for v1, v2, v3 of the new product based on feature depth or user needs. With AI systems, the versioning still applies, but the lens shifts.

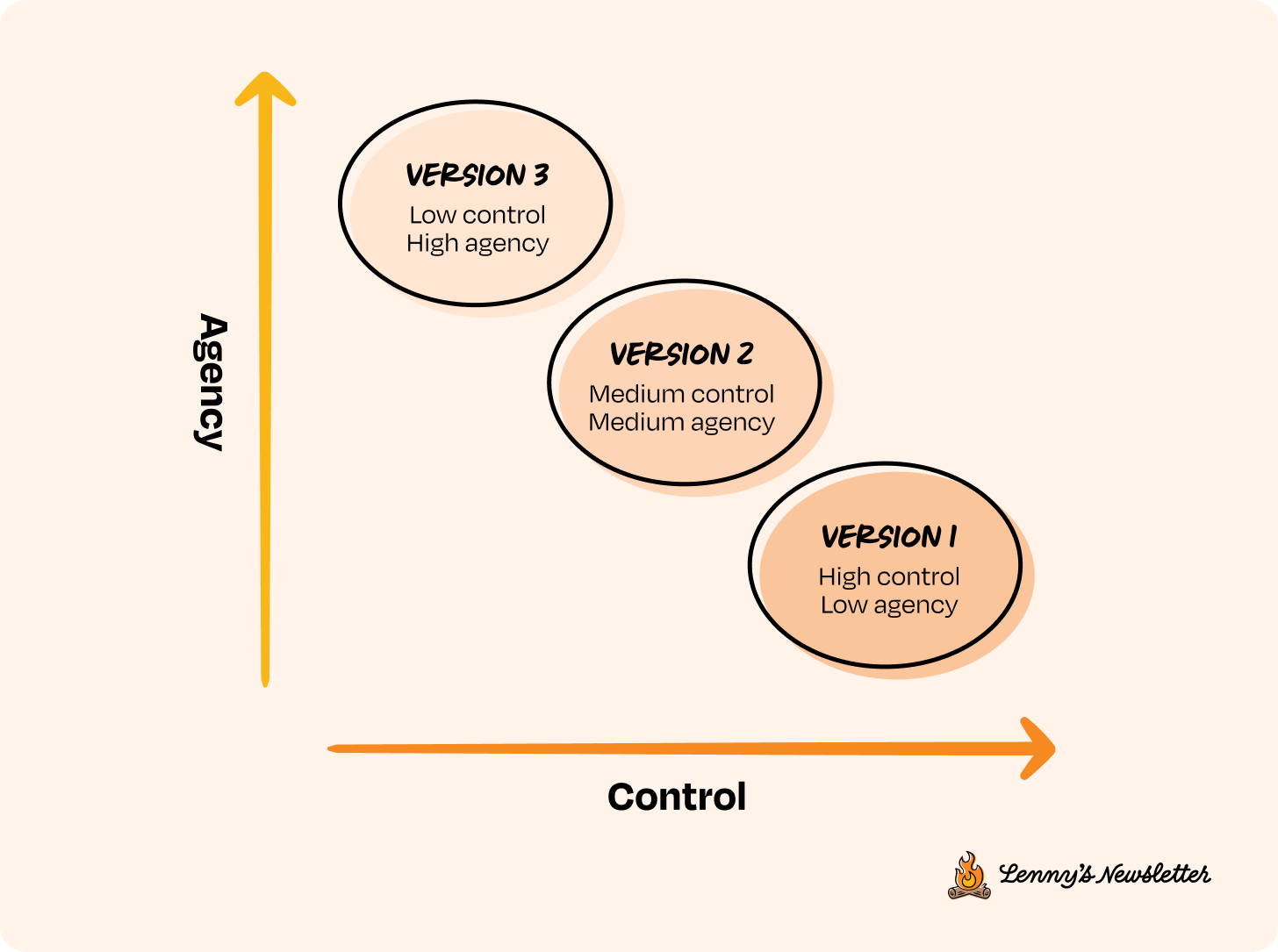

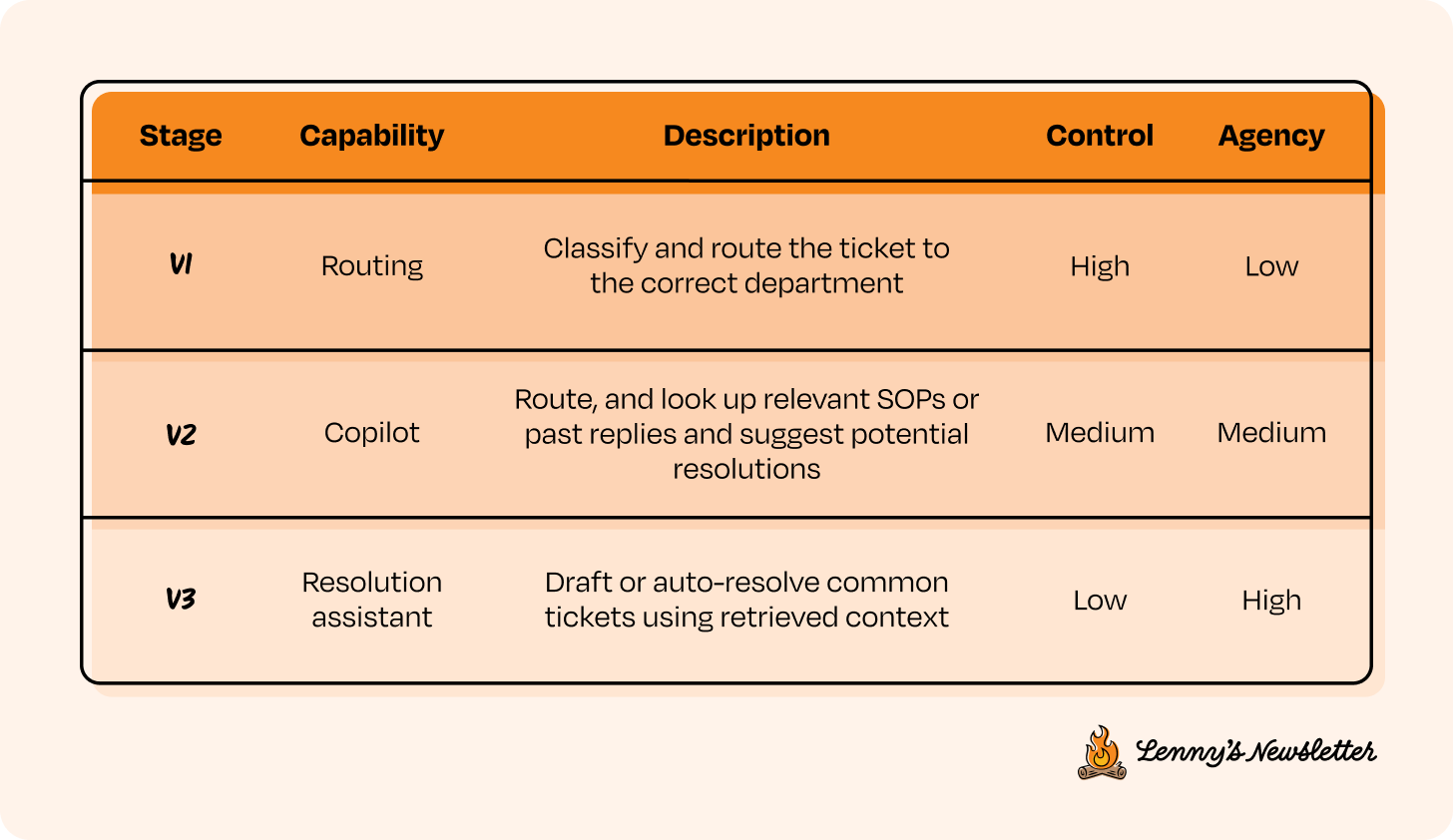

Here, each version is defined by how much agency the system has and how much control you’re willing to give up. So instead of thinking in terms of feature sets, you scope capabilities. Start by identifying a set of features that are high control and low agency (version 1 in the image above). These should be small, testable, and easy to observe. From there, think about how those capabilities can evolve over time by gradually increasing agency, one version at a time. The goal is to break down a lofty end state into early behaviors that you can evaluate, iterate on, and build upward from.

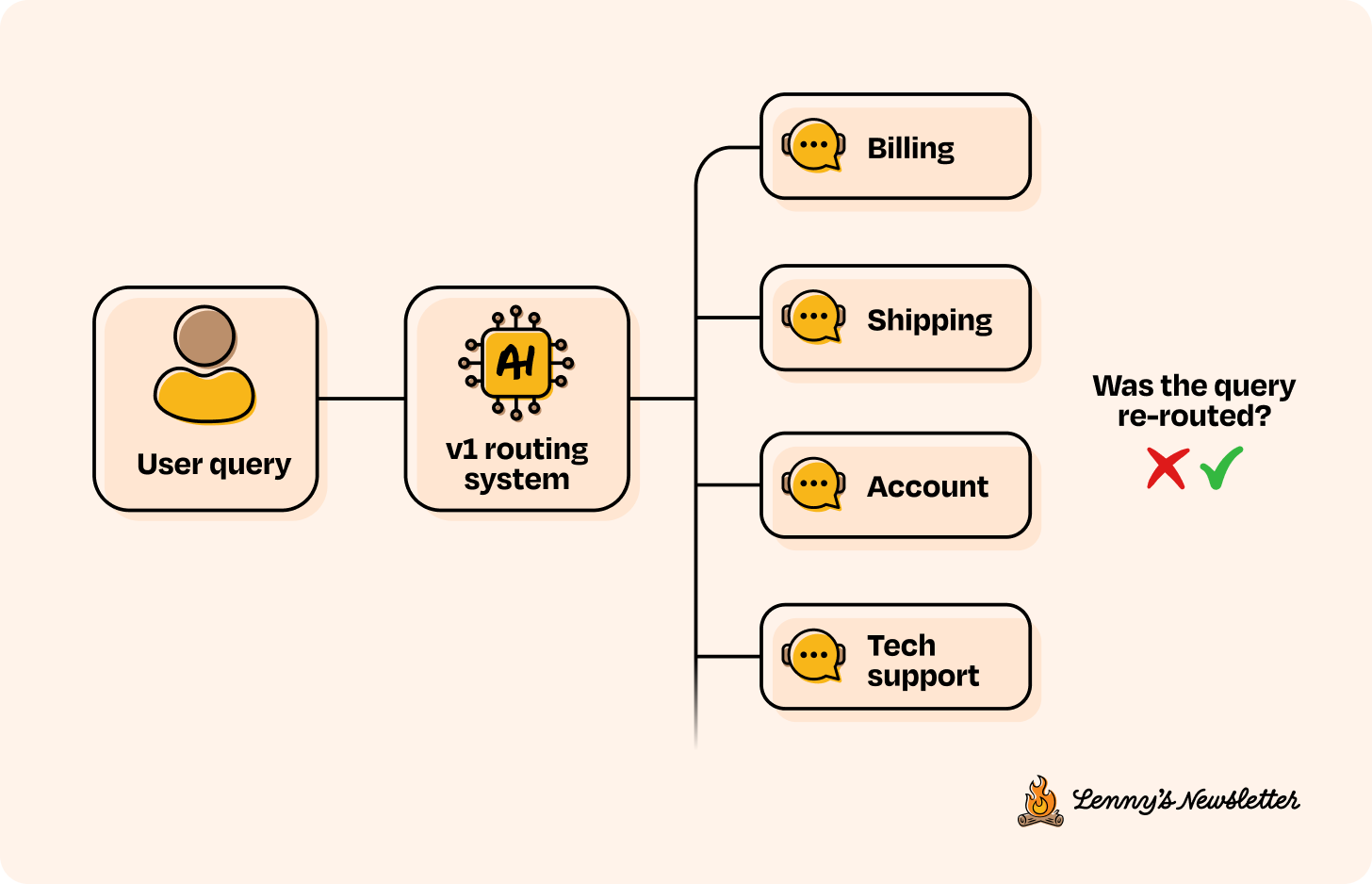

For instance, if your end goal is to automate customer support in your company, a high-control way to start would be to scope v1 (version 1) as simply routing tickets to the right department, then move to v2 where the system suggests possible resolutions, and only in v3 allow it to auto-resolve with human fallback.

Remember, this is just one approach. What it looks like in practice will depend on your product, but the process tends to be consistent: Start with simple decisions that are easy to verify and easy for humans to override. Then, as you progress through the CC/CD loop, gradually layer in more autonomy with each version.

How long you stay in each version depends entirely on how much behavioral signal you’re seeing. You’re optimizing for understanding how your AI behaves under real-world noise and variation.

Here are a couple more examples:

Marketing assistant

v1: Draft email, ad, or social copy from prompts

v2: Build multi-step campaigns and run them

v3: Launch, A/B test, and auto-optimize campaigns across channels

Coding assistant

v1: Suggest inline completions and boilerplate snippets

v2: Generate larger blocks (like tests or refactors) for human review

v3: Apply scoped changes and open pull requests (PRs) autonomously

If you’ve followed how tools like GitHub Copilot or Cursor evolved, this is exactly the playbook they used. Most users only see the current version, but the underlying system climbed that ladder gradually. First completions, then blocks, then PRs, with each step earned through usage, feedback, and iteration.

Now, because user behavior is non-deterministic, you’ll need to build a reference for what expected behavior looks like and how your AI system should respond. That’s where data comes in. Data helps break the cold start and gives you something concrete to evaluate against. We call this the reference dataset.

In the customer support automation example, for the routing version (v1), your reference dataset might include:

The user query

The department it should be routed to

Metadata used to make the decision, such as product type, user tier, or channel

You can pull this from past logs if available, or generate examples based on how your product is expected to work. This dataset helps you evaluate system performance and also tells you what context your assistant needs in order to perform reliably. Since most products start cold, aim to gather at least 20 to 100 examples up front.

We’ll continue using the customer support example to walk through the next steps in the CC/CD loop. Imagine you’re building toward a fully autonomous support system for a company. Below are the versions we’ll reference, along with their corresponding agency and control levels. We’ll refer to v1, v2, and v3 throughout the rest of the post.

CD 2. Set up application

Most people skip step 1 and jump into the setup phase too early, getting lost in implementation choices and overthinking which components are needed. But if you’ve scoped your capability properly in step 1, looked at enough examples, and curated a solid reference dataset, setting up the application should be fairly straightforward. You already know what the system needs to do, have a sense of what users are likely to throw at it, and understand what a good response looks like. Now it’s just about wiring together the simplest version that gives you a useful signal.

There’s a famous saying in software, for a reason: “Premature optimization is the root of all evil.” It applies here too. Don’t overengineer. Don’t over-optimize. Not at this stage. Just don’t. Build only what’s needed for your current version. Make the system measurable and iterable by setting up logs to capture what the system sees from the user, what it returns, and how people interact with it. This will form the basis of your live interaction dataset and help you improve the system over time. We won’t go deep into implementation here, but if you’re exposing this to end users, make sure the basics like guardrails and compliance are in place.

One more important point: When setting up the application, make sure control can be handed back to humans seamlessly when needed. We’ll refer to these as control handoffs. For example, in the customer support v1, if a ticket is misrouted, the receiving agent (the point of contact for that department) should be able to reroute it easily. Since that correction is logged, it not only helps improve the system over time but also preserves the user experience. Thinking about control handoffs from the start is key to building trust and keeping things recoverable.

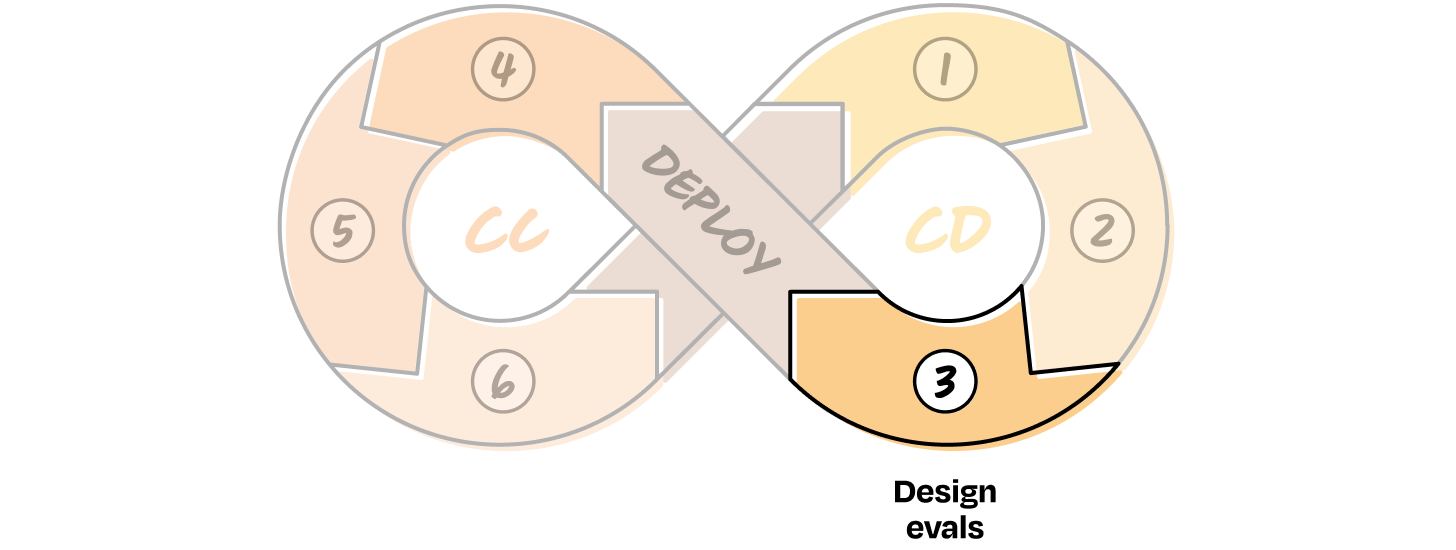

CD 3. Design evals

This is the part that usually takes a bit of thought. Before shipping anything, you need to define how you’ll measure whether the system is doing what you expect and whether it’s ready for the next step. You do this using evaluation metrics (evals, for short).

So, what are evals?

Evals are scoring mechanisms that help you assess whether your AI system is working, where it’s falling short, and what needs improvement. Think of them as the equivalent of tests in traditional software. But unlike typical unit or integration tests, where inputs and outputs are fixed and correctness is binary, AI evals deal with ambiguity.

They’re entirely application-specific and tied to the task you scoped in step 1. You’re not just checking if the system runs—you’re checking how well it does something inherently non-deterministic, like summarizing a document or answering a question. That’s why evals aren’t one-size-fits-all. They serve as the signals to guide your iteration loop, helping you tune and refine behavior over time.

For example, in the routing v1 of the customer support system, a simple but strong eval would be routing accuracy—how often the system routes to the correct department. That alone can tell you if the model is learning the right distinctions and whether or not your setup is solid.

In v2 of the customer support system, where you’re retrieving internal standard operating procedures (SOPs) or past resolutions to assist an agent, your evals shift to retrieval quality. Are the suggestions actually relevant to the ticket? Are they what a human agent would have looked at?

One of the best practices at this stage is to run evals against the reference dataset from step 1. This helps you gauge performance, validate whether your evals are well-designed, and make early tweaks to your product setup from step 2. Some teams wait until after deployment to refine, relying on real user interactions. That approach can work too, depending on the system’s risk profile and how much reference data you can collect up front.

You don’t need to over-optimize evals on the reference dataset. The goal is broad coverage across key use cases, not perfection. Production behavior will differ, but a strong eval setup gives you a dependable starting point.

To dive deeper into designing and refining evals, a great starting point is Aman’s piece.

—

Once you’ve implemented your system and verified that it’s properly scoped and instrumented, it’s time to deploy. Deployment is the transition phase between the Continuous Development and Continuous Calibration loops.

Transition: Deploy

Deployment is the fun part. But you’re not just vibe deploying (for lack of a better term 🙂) and hoping for the best. You’ve set up a pipeline that lets you learn and improve. You’re logging interactions, you’ve built in a way for humans to take back control, and you’ve put evaluation metrics in place to flag when something is off. Now’s your chance to see the system in the wild.

Boom. You deploy to a small cohort, and the system starts running.

From here, you move into the Continuous Calibration phase. This is where real-world behavior starts to show up and where you begin to learn what’s working, what’s breaking, and what needs fixing next.

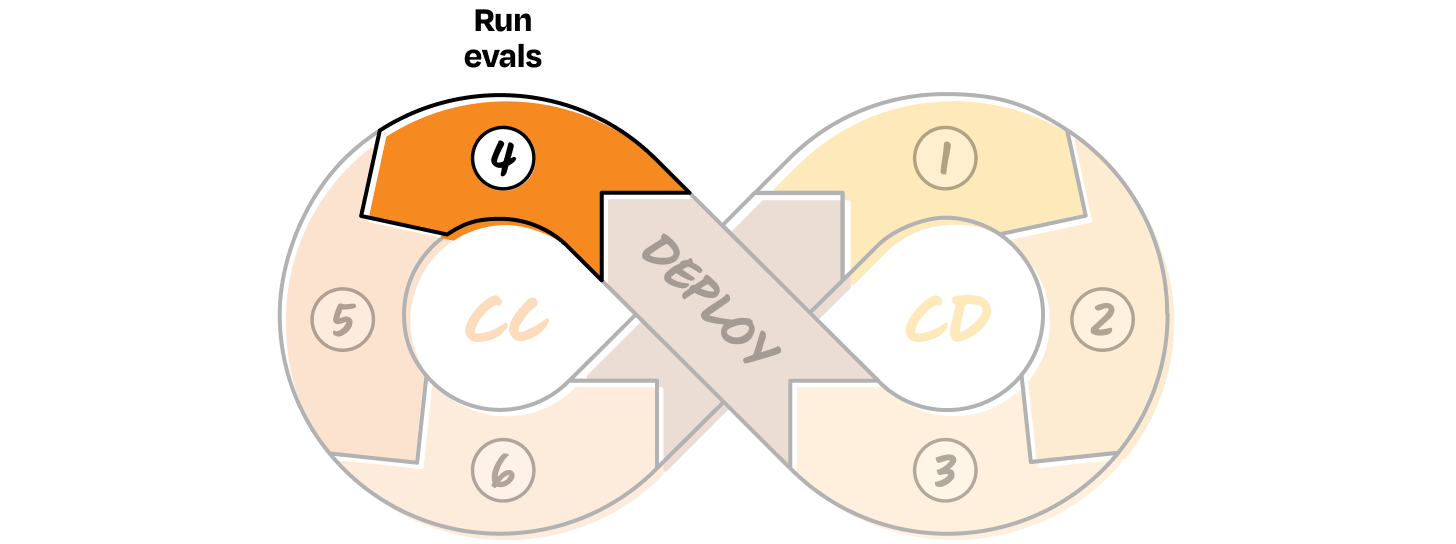

CC 4. Run evals

You designed eval metrics in the CD loop. Now that you’ve deployed and have user behavior logs, it’s time to assess how well the system actually performed. Once you’ve collected a meaningful amount of live interaction data, you can start running your evaluation. You can run them on a subset of the data or across the full dataset, depending on cost and compute constraints.

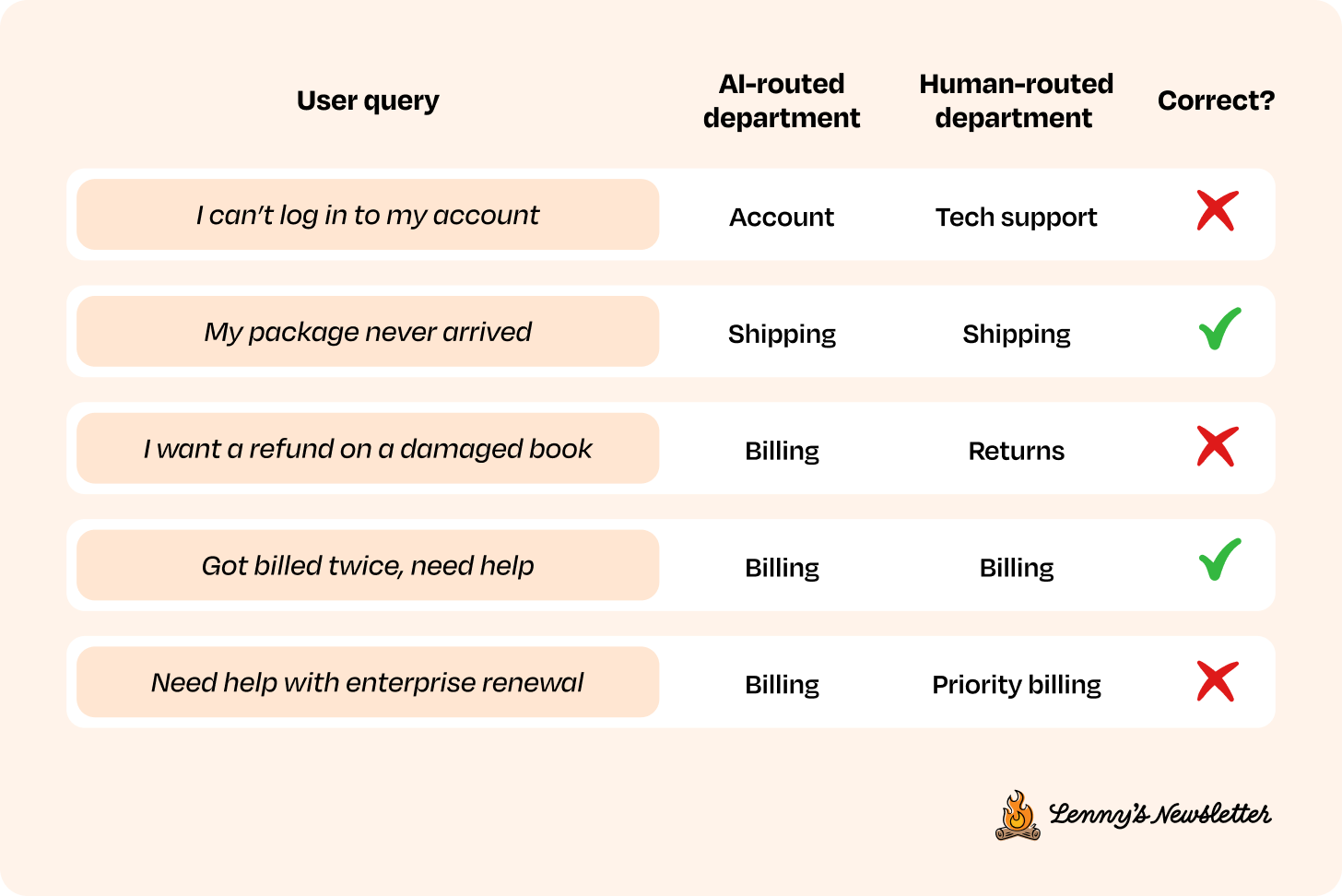

If you need to evaluate on a subset, use the unique properties of your system to decide which data points to sample. For example, in the v1 for the customer support system, you might use logs showing whether a human agent rerouted the query to a different department as a proxy for routing accuracy. In more complex systems, you could look at things like the number of conversation turns, whether users gave thumbs-up or thumbs-down feedback, or other in-session signals.

Control handoff logs can also provide valuable eval signals, especially when they capture how a human would have stepped in or adjusted the outcome.

Example evaluation for customer support system v1

Depending on your use case, choose the most representative sample of live user interactions to run your eval metrics on. And if your interaction data is small enough (2,000 to 3,000 logs), go ahead and run them on the full dataset.

CC 5. Analyze behavior and spot error patterns

When you look at your evals, maybe they look solid. Maybe they don’t. If you’ve done steps 1 through 3 of the Continuous Development phase well, your metrics are probably somewhere in the middle, which means there’s something to optimize.

Now it’s time to start manually reviewing your data. It’s one of the most underrated but necessary parts of building AI systems. A simple strategy is to begin where your eval metrics are weakest. That’s usually where the most valuable signal is.

For example, in the customer support system routing v1, you might:

Pull 20 to 50 low-accuracy tickets per department

Focus more on departments where scores are lagging (maybe Refunds is underperforming, while Billing looks fine)

Look at what the user said, what the system did, and what the outcome was. Depending on your application, this might be a single interaction or a multi-turn session. Your eval metrics should help you identify where things went wrong and guide you to the point of failure.

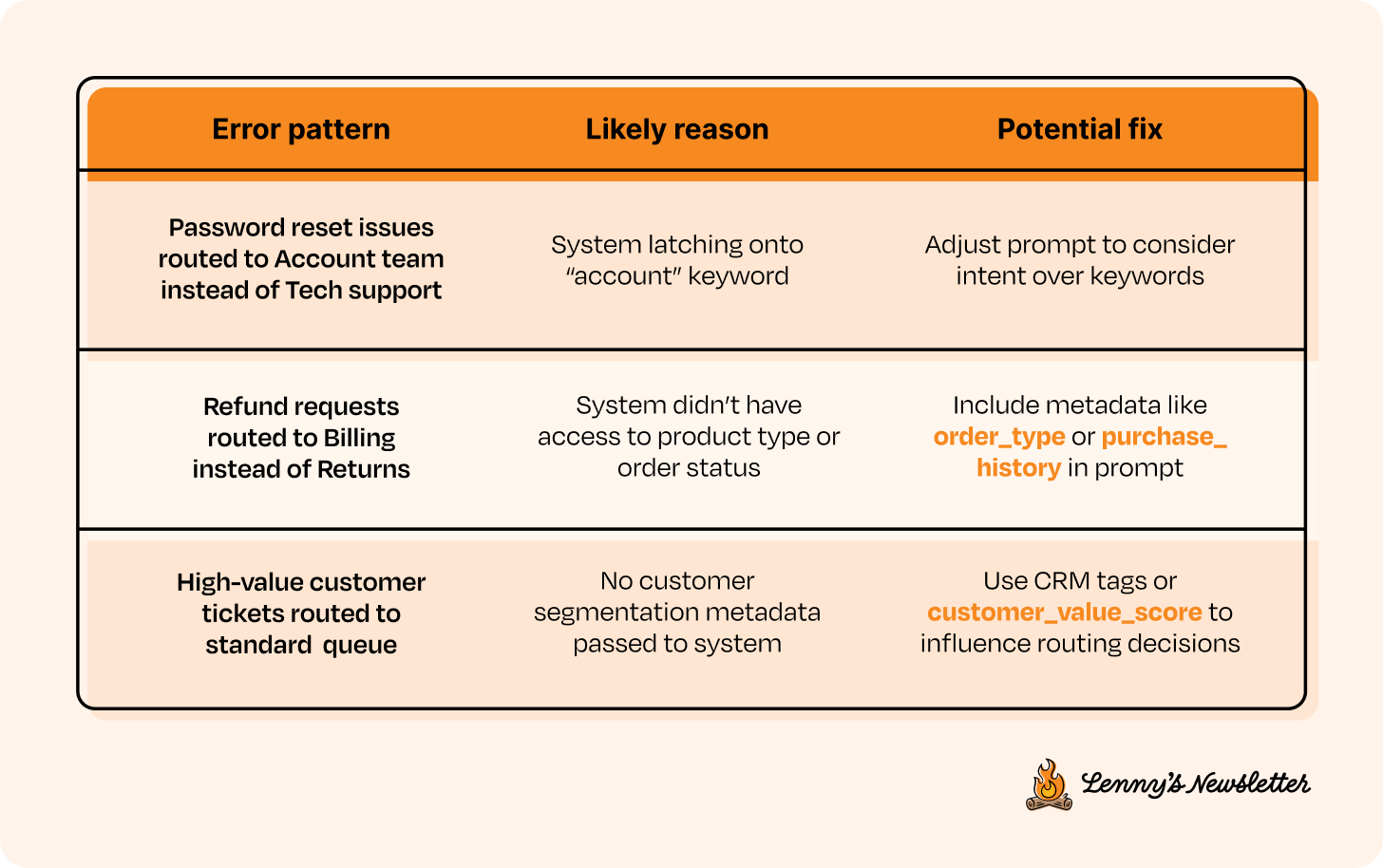

Once you’ve manually reviewed enough examples, you’ll start to notice repeat error patterns. This is where you begin documenting them. A simple table format works well at this stage:

These patterns show you what needs to change in your system’s logic, prompts, or inputs. They also help you scope the next version more intentionally.

CC 6. Apply fixes

Once you have actionable error patterns, you can start outlining ways to fix them. This could be anything from a simple prompt tweak to switching to a better model, improving retrieval quality, or adding new components to break down the task. What you change depends entirely on what broke.

Remember how in step 2 of the Continuous Development phase we said not to overengineer? That’s because this step is when you should engineer more. Evolve the architecture, but do it intentionally—backed by data, not guesswork.

This step is often iterative in itself. You apply a fix, run your eval metrics again, and either keep refining the current version or cycle through steps 2 to 5 until the system performs well enough. And since you already have data, you don’t need to redeploy each time.

Also, it’s not uncommon for the eval design itself to fall short. That’s because evals are often designed using the reference dataset, which is based on what you expect users to do. Real user behavior, however, can be very different. That non-determinism can throw off your evals too. As you go through steps 4 and 5 again, you may find consistent places where the evals missed issues or gave high scores to flawed outputs. So step 6 may also involve revisiting and rebuilding your evals—and that’s completely normal. You’ll likely end up running multiple rounds of evaluation as you continue to shape the product. Sigh . . . it’s all part of the process.

—

Once you get to the end of step 6 for the first time, you’re probably getting the hang of it. You’ll go through this loop multiple times, gradually reducing control, allowing the system to become more autonomous, and letting product features guide your design choices. Remember that deployment is just one part of the bigger picture. Most of the work is in designing things well.

Which brings us to a small rant: Too many people focus almost entirely on implementation, chasing the latest tools and frameworks, but end up making costly mistakes. We started with a large goal, broke it down, and used more complex solutions only when they actually solved a real problem.

Never lead with the tech. Let the problem, evals, and data guide what gets added next. That’s how you keep non-determinism in check with AI products.

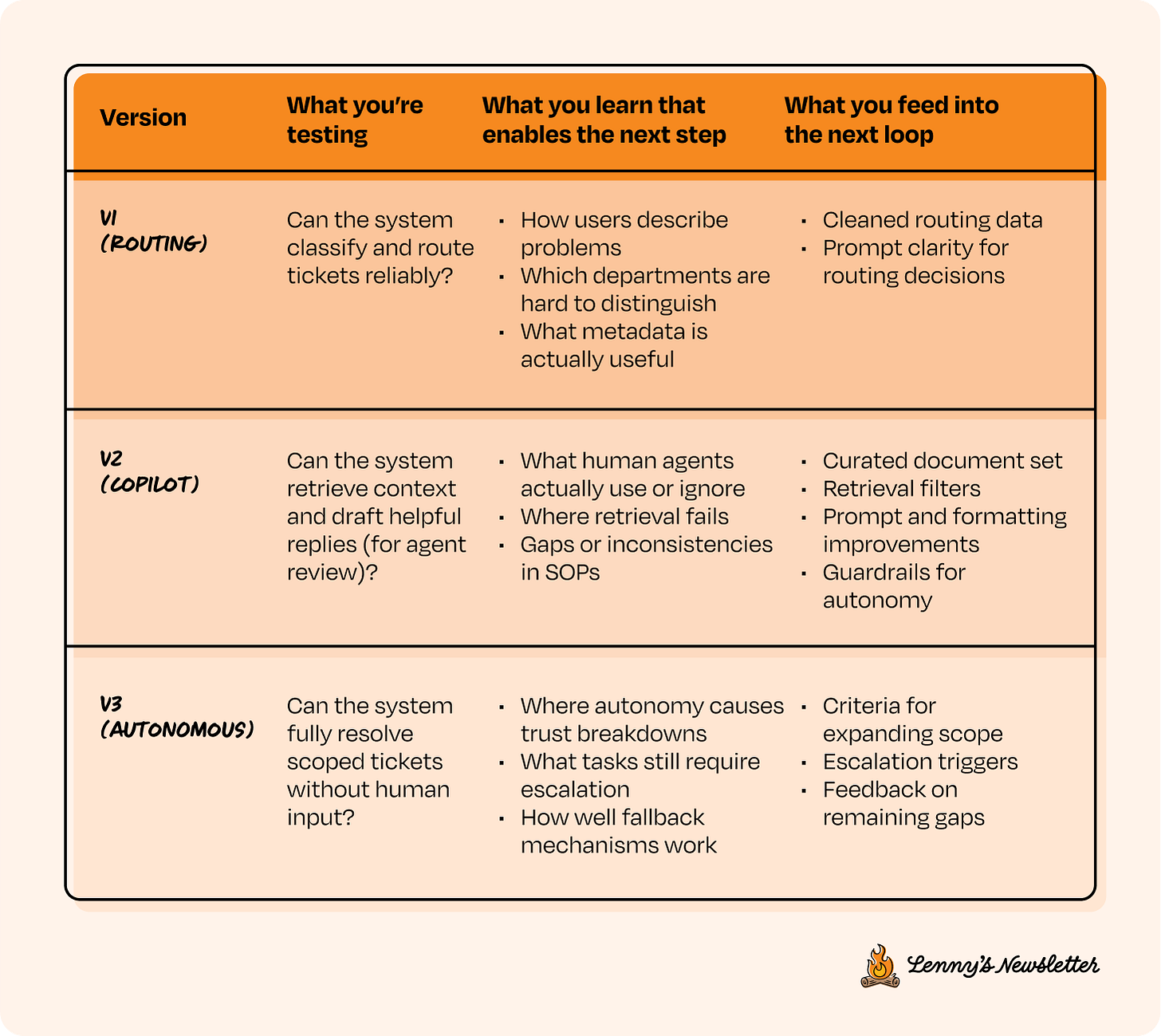

Putting it all together: A CC/CD loop for customer support

Here’s a potential table that breaks down the problem into multiple versions, each adding more agency over time. It also outlines the flywheel you could build at each stage, using the customer support example we’ve been discussing. Each iteration sets up the next. This is just one way to approach it.

Use this as inspiration to think about how you could break down your own product to build and scale intentionally.

If you shipped a fully autonomous support system (v3) right away, a lot could go wrong fast. Take one simple example: A refund request gets incorrectly tagged as a billing issue, the system pulls the wrong SOP and generates a plausible but incorrect resolution, and the user ends up confused and loses trust in the product.

And while you may have evals in place to flag that something went wrong, you’re now stuck untangling a chain of failures. The final mistake ended as a generation error, but it started at routing, was compounded by missing context, and led to a poor outcome. This is just one simple case, but you can already see how quickly things can get complicated.

The CC/CD approach helps you avoid that spiral. In the customer support v1, the system handles only ticket routing, giving you signals on how users phrase issues, which departments are often confused, and what metadata actually matters. You then use that to improve routing logic and refine prompts before moving on. In v2, the system drafts responses based on SOPs, but a human still reviews them. This helps you understand where retrieval breaks down and which documents need updates. By v3, the system is ready to take on more agency by resolving scoped tickets on its own. But now you know which queries are safe to automate and where fallback is needed.

Where to go from here

AI systems have the incredible potential to operate with some level of agency, but getting there is rarely about stacking complex tools or scaling things with brute force. It’s not about writing the perfect prompt either. Creating an AI system that saves time, money, and energy through effective automation is about solving the actual problem, step by step, by understanding its nuances.

We often compare working with AI to onboarding a new teammate. The teammate might be brilliant, but they don’t yet know how your team works. You don’t hand them your highest-stakes projects on day one. You start small, observe, build trust, and, as they show what they can handle, you gradually expand their scope. AI systems need that same path. That’s what the CC/CD framework is designed to support.

At the heart of CC/CD is judgment: the kind that helps you decide what to ship, how to protect users when things go wrong, when to hand control back, and how to define what “good enough” looks like.

There’s no one-size-fits-all for how much capability to give each version, how long to gather data before moving forward, or how tightly to scope. It depends on your product, your users, and your timelines. Some products need weeks of iteration. Others can move faster. That’s where your judgment comes in.

Most of that valuable product thinking already lives in successful product leaders. CC/CD simply gives it structure. The framework offers a loop, a rhythm, and a shared language to apply that already-great product instinct to AI systems.

Thanks, Aish and Kiriti! You can follow them on LinkedIn, and check out their popular Maven course and their upcoming free lightning talk that explores this topic in depth.

Have a fulfilling and productive week 🙏

If you’re finding this newsletter valuable, share it with a friend, and consider subscribing if you haven’t already. There are group discounts, gift options, and referral bonuses available.

Sincerely,

Lenny 👋

Excellent framework. I like the ladder of earned trust with the CC approach. IMO, calibration should also tie to real signals like task success, recovery speed, and user trust, alongside accuracy metrics.

Lenny, this was an easy to read and be able to follow your short course on CC/CCD, it easy to forget that even though we are sill in the engineering business of AI, precision is the order of the day - you go too fast to meet deadlines or launch a product/feature....things break and customer trust breaks.